In a Peruvian valley only recently touched by urbanization, Yale scientists have found evidence of ancient Andean metallurgy dating as far back as 3,400 years ago, almost a millennium earlier than the skill was previously believed to have existed.

Thin copper foils -- some of them gilded with gold foil -- were discovered at a site called Mina Perdida (Lost Mine) just south of Lima in the Lurin Valley. The foils reveal that artisans were heating and hammering natural metal ores long before the introduction of smelting roughly 2,000 years ago, according to anthropologist Richard L. Burger, director of the Peabody Museum of Natural History, who collaborated with geologist Robert B. Gordon on the study.

Their findings, published in the Nov. 6 issue of the journal Science, push back the date that the Central Andes are believed to have become the "hearth of metalworking" in Latin America, Burger says. The skills perfected by artisans there later became important in the religious life of the Incas of Peru and may have influenced the Aztec and Maya civilizations in Mexico beginning about 2,000 years ago, he notes.

"These early examples of Andean metalworking from Mina Perdida show three patterns that were to characterize the Central Andean metalworking tradition for the next three millennia -- an unusual concern with the production of very thin metal foils, the gilding of copper, and the close association of metalworking with religious ritual and the supernatural realm," Burger says.

He adds that the development of metallurgy in the New World appears to have followed much the same pattern as it did in the Old World, with a long period of experimentation with naturally occurring metals before the creation of more sophisticated alloys, such as bronze, or the extraction of metals from ore deposits by smelting. Scientists had speculated that early New World artisans skipped this experimental stage and moved directly into smelting, welding and the creation of colorful metal alloys -- a theory challenged by this new evidence.

"It certainly shows that this technological development in the New World was occurring at an earlier date than recognized," says Burger, whose previous research at Mina Perdida showed that monumental architecture and complex societies first appeared in the New World between 3,500 and 5,000 years ago. That cultural flowering occurred about the same time the great pyramids were built in Egypt and city-states first flourished in Mesopotamia, an area considered the "cradle of civilization."

"Nowhere did impressive cultural developments occur earlier in the New World than on the west coast of Peru," Burger says. In fact, the most spectacular Andean monuments were built nearly 2,000 years before the rise of the Maya in Central America and 3,000 years before the Aztecs.

Metallurgy appears to have arisen in the pre-Chavin period, he says. The Chavin culture is named for a ceremonial center called Chavin de Huantar that flourished in the highlands of central Peru about 2,500 years ago. While none of the foils discovered at Mina Perdida were shaped into recognizable objects, such foils were the basis of elaborate metal artifacts used by Chavin societies in religious ceremonies and in costumes of the elite between 600-200 B.C. "Many of the features we assumed had appeared with the Chavin culture in the first millennium B.C. had their roots in pre-Chavin societies," Burger says.

Carbon dating of the foils, which ranged between 0.1 and 0.05 millimeters in thickness, indicated they were produced between about 1410 and 1090 B.C., roughly 3,400 to 3,100 years ago. The analysis was completed by Gordon, professor of geology and geophysics at Yale and a specialist in historical metallurgy, using a scanning electron microscope.

The foils were found during a 1991 excavation in an area 25 kilometers south of Lima on a natural terrace about 8 kilometers from the Pacific Ocean. The foils were buried in a low platform mound when the platform was expanded. Excavations in 1993 and 1994 also unearthed fragments of copper foil on the summit and terracing of the main pyramid.

"These technological developments occurred in an era marked by a relatively egalitarian society, preceding the emergence of strong social stratification and state organization in this area," Burger concludes. Funding was from the Selz Foundation, the Heinz Charitable Trust, the Joseph Fisher Foundation and Yale University.

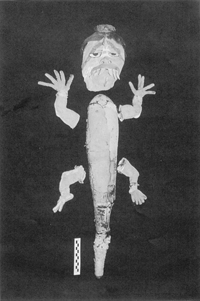

| Along with copper and gold foils, scientists found this human effigy -- with fangs, hinged limbs, and a body made from a gourd -- buried on the terrace of a large pyramid at Mina Perdida. The artifacts, dated between 1405 and 1120 B.C., most likely were used in sacred ceremonies by the farmers who lived in the lower valley of the Peruvian coast.

| |

November 16-23, 1998

November 16-23, 1998