The Entrance Court, previously adorned with only a few works of art, now is resplendent with about two dozen bronze and stone sculptures. Upstairs galleries have been reconfigured and refurbished. And, new vistas have been introduced.

"People will see a brand new British Art Center," says Patrick McCaughey, the center's director. "It's been renewed from top to toe." The artistic alterations were made after the BAC underwent a massive structural overhaul. The main focus of that undertaking was the roof, which was completely refurbished. The center's public galleries were closed for all of 1998 to accommodate the renovation project, which was managed by Turner Construction Company of Shelton, Connecticut.

Located at 1080 Chapel St., the Yale Center for British Art first opened its doors to the public in 1977. Eleven years earlier Paul Mellon, Yale Class of 1929, had donated funds to construct and endow a building to house his collection of British art. Architect Louis I. Kahn was selected to design the museum. Although Kahn died while the center was being built, all major decisions had been made prior to his death. The building -- an amalgam of steel, concrete, white oak, travertine marble, wool and linen -- is considered a landmark of modern architecture. The museum houses the largest and most comprehensive collection of British art ever assembled outside the United Kingdom.

Although the renovation has brought many structural changes to the British Art Center, "we stuck faithfully to the intention of the architect," says Malcolm Warner, curator of paintings and sculpture.

McCaughey adds that in many parts of the building "the irony is that we look as though we have changed nothing, just returned Kahn's building as close as possible to its original pristine state."

Among the structural characteristics unique to the BAC is "the wonderful light," says McCaughey, which he considers "the secret of the British Art Center." The museum's roof, comprised of 56 intricately crafted individual domes, allows natural light to stream into the building. The sense of animation that the natural light brings to the fourth-floor paintings is not easily reproduced with artificial lighting, notes McCaughey. The roof had, however, begun to leak and was in dire need of renovation after 20 years of withstanding New England weather.

"The roof has been completely repaired," says McCaughey. "All 56 domes have been lifted off and refitted, a new slope has been added to the flat surface for better drainage, and the mansard has been rebuilt from scratch to run around the roof."

New carpet was laid throughout the building, and every wall in the public galleries was completely replaced with new backing boards and linen (the dismounted linen was donated to the School of Art). On the fourth floor, which houses the permanent collection, movable -- or "pogo" -- walls have redefined the space.

"The area has been reconfigured to enable Malcolm Warner and assistant curator Julia Marciari Alexander to reinstall the collection with an original and fresh eye, bringing to the walls liveliness, new themes and many less familiar works," says McCaughey.

Interestingly the fourth-floor walls, though always portable, have not been moved about much, Warner notes. But with the refurbishment "we moved almost every movable wall." The result, he says, is "on the whole a much more open gallery, with more light and air." The movable walls also allow for paintings in the permanent collection to be arranged differently in order to make a common theme more apparent or to bring out a different motif.

"There's more breathing space," says Warner. "The space is much more sympathetic to the works." A label of interpretive text informing visitors about the artworks has been added to each room in the fourth-floor gallery. In addition, the collections are more densely hung than they were previously. Visitors may notice, for example, an increased number of John Constable's landscapes on exhibit.

Also on the fourth floor are the Long Gallery (formally known as the Study) and the Founder's Room, both of which are designed for intimate viewing. "The Long Gallery is arranged so that each bay focuses on a particular topic and addresses those aspects of the collection not hung in the permanent galleries," notes McCaughey. "Thanks to a most generous gift from our benefactor Paul Mellon, the Founder's Room has been completely redesigned to provide, at last, a comfortable, personal and intimate room for special occasions."

The British Art Center's conservation laboratory, located on the third floor, also has been renovated. Since chemicals that remove adhesives and deteriorated coatings can be hazardous to the conservators or can potentially damage works of art, a system was installed to ensure environmental safety. The laboratory now has a new state-of-the-art ventilation system that incorporates a large chemical-fume hood, chemical-exhaust canopy and flexible vapor-extractor arm or "elephant trunk." The water-purification system has been improved to allow aqueous cleaning of paper-based artworks. Such cleaning not only improves the appearance of these art works, it also helps to neutralize acid papers, which prolongs their life. The Auto-Flow fume-hood system is a donation from Paul Holland and W. Gary Peters of GreenTech, Farmington, Connecticut.

On the second floor, in the British Art Center's Library Court, previously exhibited works have been repositioned. "The Library Court has been rehung to give our internationally renowned collection of George Stubbs a new prominence," explains McCaughey. "The two monumental paintings of 'Horse Attacked by a Lion' and 'Lion Attacking a Stag' are shown at normal viewing height instead of high over the viewer's head. You can see those lions snap and bite now that you are close up."

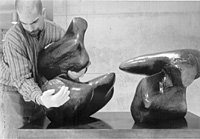

The same sense of intimacy is evident on the first floor, where a collection of sculptures by Henry Moore greets visitors. This "dramatic installation" is one of three exhibits marking the reopening of the museum (see related story, below). Even after the show completes its run at Yale, the Entrance Court will continue to be used as a display area, with an emphasis on contemporary sculpture, says Warner.

The Yale Center for British Art is not just a gallery, McCaughey stresses. It is also a research facility, serving teachers, scholars and students of art. "The center has a dual function. It plays an integral part in the teaching and research life of Yale University and operates as a public art museum. Regularly it brings scholars to New Haven from around the world."

The center's collection, which extends from the Tudor period to the present day, encompasses paintings, sculpture, drawings, watercolors, rare books and manuscripts. About 1,500 paintings are in the permanent collection. Among the artists represented are William Hogarth, Joshua Reynolds, J.M.W. Turner, Richard Parks Bonington and John Constable. The most recent acquisitions include works by Damien Hirst and Rachel Whitehead. The department of prints and drawings provides a survey of the development of English graphic art, with about 30,000 prints and 20,000 drawings. Special-interest areas include sporting and topographical prints. The department of rare books and archives houses about 20,000 volumes, including several early maps and atlases. Approximately 20,000 books, periodicals, sales catalogues and dissertations are in the reference library.

With the reopening, the Yale Center for British Art will resume its regular presentation of talks, concerts and films. For more information, visit the center's web site at www.yale.edu/ycba.

-- By Felicia Hunter

PHOTO BY MICHAEL MARSLAND

| Exhibition technician Greg Shea moves one of the Henry More sculptures that will be on display when the center opens. See related story on the three major exhibits that have been installed to mark the grand reopening.

| |

January 18-25, 1999

January 18-25, 1999