Like a determined detective, or a prospector mining for hidden gems, Camara Dia Holloway has spent countless hours over the last few years delving through archives in museums and libraries in search of faces that history has forgotten.

A doctoral candidate in the history of art, Holloway has been looking for portraits taken by African-American artist-photographer James Latimer Allen, who ran a portrait studio on New York's West 121st Street during the 1920s and 1930s, when Harlem was an emerging center of black culture. Allen's clientele were key figures in that Harlem Renaissance, some of whom are still famous and others whose accomplishments have been lost over time.

In her searches through archives at Yale and elsewhere, Holloway has uncovered scores of previously unknown images by Allen. A number of the vintage visages she's discovered are featured in "Portraiture and the Harlem Renaissance: The Photographs of James L. Allen," an exhibit that Holloway organized at the Yale University Art Gallery. The show will be on display through April 11.

Holloway has long been fascinated by the impact that visual representations of African Americans have had on black culture. As an undergraduate at Barnard College, she developed an independent research project titled "Snow Jobs: The Images of African American Women in American Culture." She also co-curated the 1993 exhibit "Imaging Blacks: African Americans in American Film" at the Schomberg Center for Research in Black Culture, where she worked for a year as assistant to the director of exhibitions.

Holloway is now in her fifth year of study at Yale, having earned Master of Art and Master of Philosophy degrees in 1995 and 1998, respectively. As a teaching fellow in the history of art department, she has had the opportunity to both expand and share her study of the visual representations of blacks while leading sections for courses such as "Survey of American Art" and "The Black Atlantic Visual Tradition."

"Photography is the visual medium that most intrigues me," says Holloway, who is now working on her dissertation, titled "Shedding the Old Chrysalis: Race and Modernity in American Photography between the Two World Wars." In her thesis, Holloway is exploring issues of identity, modernity, and racial identity and politics in the work of several photographers, including Walker Evans, Doris Ullman and James L. Allen.

Unlike Evans and Ullman, white photographers who focused primarily on the lives of blacks in the rural South, Allen offered a very different portrait of African Americans. His clients were members of the black elite in Harlem, and included artists, writers, scientists, business figures and socialites. Most of these individuals, like Allen, were dedicated to the idea of bringing about "a self-determined redefinition of black culture," as embodied by the image of the "New Negro," says Holloway.

Unlike previous portrayals of blacks as servants or slaves, the image of the "New Negro" was "polished, sophisticated and modern," Holloway explains. "Allen's photos were key to that process," she adds. "These are the photographs of choice of a core group of black elite. Allen gave them a mirror on which to project themselves."

In fact, Holloway writes in the catalogue that accompanies the Yale Art Gallery exhibit, "To commission a portrait from Allen was a deliberate decision to acquire an image most consistent with the Harlem elite's sense of self. Allen's patrons desired images by an artist who shared their world view."

Like many of his clients, "Allen considered himself an artist," says Holloway. "He was creating an artistic expression through his photographs that was similar to the Harlem elite's own artistic agenda." In fact, one of the earliest dated images in the exhibit is a portrait of the photographer himself titled "Self-Portrait, Wearing Artist's Smock" (1926). "Wearing the accoutrements of the artist -- the smock and bohemian languor of a 19th-century romantic genius, he defied then-current notions of what black people could be," writes Holloway in the exhibit catalogue.

Allen promoted the image of the "New Negro" even in the photographs of anonymous models which he created for advertisements or illustrations in black periodicals. These images, bearing such titles as "Dark Beauty" and "Brown Madonna," are celebrations of racial pride, says Holloway.

Although his studio flourished for nearly two decades and his work was widely disseminated through the black publications of his day, Allen has until recently been a neglected figure in African-American history, notes Holloway. As a result his photographs remain largely uncatalogued.

It was while doing research at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library that the Yale student "stumbled" upon the untapped reservoir of Allen images there. "I kept happening upon images, and I could see they were by him," says Holloway, who has since conducted similar searches in other archives. "You begin to develop an instinct about where to look," she adds. To date, Holloway has uncovered 200 previously unidentified images by Allen. "These photographs were all unindexed and unidentified," she explains. "I had to do a lot of digging."

Holloway first began working on the exhibit "Portraiture and the Harlem Renaissance" last year, when she was the 1997-98 Florence B. Selden Intern at the Yale Art Gallery. (She previously held two internships at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

One of the most challenging parts of putting together the Yale show has been finding out information about the individuals whose portraits are on display, notes the Yale student. While some of those pictured are still well known today, such as actor Paul Robeson or the poet Langston Hughes, others are less famous, and still others have had their accomplishments erased by time.

In some cases, Holloway had to scour the society papers of the day to find references about the individuals pictured. "Many of them have been lost -- forgotten," she says. "For those, you tend to find just fragments of information."

Holloway will be one of the featured speakers at a symposium on "Black Visual Culture During the Harlem Renaissance," which is being sponsored by the Yale Art Gallery in conjunction with "Portraiture and the Harlem Renaissance: The Photographs of James L. Allen."

The event, which will be held 1-3 p.m. on Saturday, Jan. 30, will feature four talks: "Race Films and Oscar Micheaux" by Jayna Brown, a graduate student in African-American studies at Yale; "Malvin Gray Johnson, Painter" by Jacqueline Francis, a graduate student from Emory University who currently holds a fellowship at the National Gallery; "James Latimer Allen, Photographer" by Holloway; and "The Anti-Lynching Campaign of the NAACP During the Twenties and Thirties" by Leigh Raiford, graduate student in African-American studies at Yale. The event will be moderated by Jonathan Weinberg, associate professor of the history of art.

In addition, there will be an art à la carte talk about the exhibit on Wednesday, Jan. 27, at 12:20 p.m. Portrait photographer Dawoud Bey will be the featured speaker.

Both events are open to the public free of charge.

The Yale University Art Gallery is located at 1111 Chapel St. Admission is free to the museum, which is open 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesday-Saturday and 1-6 p.m. Sunday. For information, call 432-0600.

-- By LuAnn Bishop

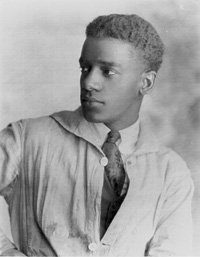

| Artist-photographer James Latimer Allen (1907-1977)

James L. Allen grew up in New York City at a time when Harlem was the center of a "renaissance" of black culture. He became interested in photography as a student at DeWitt Clinton School, where he was a member of the Amateur Cinema League. At the age of 16, while still in high school, he began a four-year apprenticeship in photography at Stone, Van Dresser and Company, where the white owner, Louis Collins Stone, and his wife offered encouragement to Allen and other talented young African Americans. In 1927, Allen submitted his work for exhibition in the fine arts category to the William E. Harmon Foundation Awards for Distinguished Achievements Among Negroes, where he won an honorable mention. His six-year association with the Harmon Foundation not only garnered Allen such awards as the Commission on Race Relations Prize for Photographic Work, but also earned him recognition among Harlem's cultural leaders. Allen produced both portraits for individuals and commissioned works for advertising agencies at his studio at 213 West 121st St. His photographs were published in such black journals as Opportunity, The Messenger and The Crisis. During the Depression, in addition to his portraiture commissions, Allen photographed exhibition installations and individual artworks for the Harmon Foundation, and his portraits of artists at work in the Harlem Community Art Center offer a record of the artistic life of Harlem before World War II. His professional career as a portrait photographer ended with his enlistment in the army, where he served with the Office of Strategic Services. For the rest of his life, Allen lived in Washington, D. C., working for the government and engaging only in amateur photography.

| |

January 25-February 1, 1999

January 25-February 1, 1999