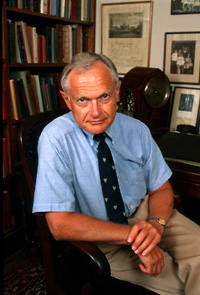

Dr. Sherwin Nuland

|

surgeon's fascination with the body

Dr. Sherwin Nuland, surgeon, teacher, medical historian and prize-winning author, has been touring the country the last four months, speaking about his most recent book, "The Mysteries Within."

As in "How We Die," the book for which Nuland won the National Book Award, he takes readers of "The Mysteries Within" through medical myths and misconceptions of the human body, this time focusing on specific organs -- the stomach, the liver, the spleen, the heart and the uterus.

His descriptions are laced with anecdotes about patients who, by virtue of their ailments and diseases, became symbols of watershed moments in Nuland's training as a surgeon. He also discusses the role of "luck" -- how all of a physician's training, experience and talent can be enhanced by a simple stroke of good fortune.

Nuland recently took the time to speak about his new book, his next project and changes in the medical profession. The following is an edited version of that conversation.

When I wrote "How We Die," so much of which is highly personal (a lot of it deals with things that happened in my childhood and teenage years), I got all these letters. Many of the letters said "We really want to hear more about your family." There are many events and emotions in those chapters, especially from the early years of my life, that came to the surface when I was writing the book. ... When those letters came, I thought, "You know, it's time to write about this, to write about childhood." So that's what I'm going to do, after some months of reflection. I'll probably start on it this summer.

I realized in writing "How We Die" that although I could describe very well the small aspects of the human body, how it functions ... I hadn't really presented an overall book on how the body works. It seemed to me that someone who had spent his life trying to explain complicated things to people who really don't have a scientific education ought to try doing that.

There are a couple of things that are happening. One is the general patient autonomy movement in medicine -- taking control of your own medical destiny. We call it, in the general sense, the 'self-determination movement,' and it has enlarged in the past 15 years. So from that point of view, people have wanted to learn a lot more. The other thing is that science education has been inadequate in this country for about 25 or 30 years. And so we get people poorly educated in science who nevertheless want to know about their bodies. In order to do that a writer has to develop a literary technique, or a conversational technique, that makes it easy for those people. Then there is this phenomenon that we are witnessing in comparative literature and in departments of English. People are writing books about the symbolism of the body.

That's right. People would turn their faces away from it. They didn't want to know. When I was a kid no one wanted to know about disease. Certainly no one wanted to know about death. That began to change just about the same time as the patient autonomy movement began in the 1970s.

I have two favorite organs. The heart just absolutely fascinates me. It's always fascinated me, this autonomous thrusting thing sitting in your chest. It functions whether or not there are nerves attached to it. It's going to go do what it wants to and it responds to our emotional state. It responds to any little stimulus from the outside. We have no control over it.

The other organ that fascinates me for a totally different reason is the spleen. It used to be called in Roman times "the organ of mystery" because no one knew what it did. One of the reasons that I became interested in the spleen was because in the early days of learning how to treat Hodgkin's disease there was a surgical technique involved and I became the surgeon at Yale-New Haven Hospital who did all those operations. So I ended up taking out 90 spleens over a relatively short period of time. I became focused on that organ.

I took a year's leave of absence to write "How We Die." ... I started on Jan. 2, 1992, because my leave was supposed to be that year, 1992. I began writing about 8:15 a.m. About 10:30 a.m., my wife, who wasn't working that day, walked into the kitchen and I said to her, "You know, I really like this life. This is a nice life." ... So for the rest of the year we talked it over and thought about it. I had been a surgeon for 30 years. As much as I loved it, it was a demanding life. And things were starting to change in surgery. It had lost some of its attractiveness for me. I always thought surgery was great fun for about 27, 28 of those years. So we talked it over and about month number nine I decided not to go back to any clinical work. I'm pretty much a full-time writer.

I loved it. It was the most wonderful way to live my life. I used to wake up with enthusiasm every day until toward the very end. To my astonishment, it was over, it was done. There must have been some emotional course that I was on that was preparing me to leave it. What I miss is the great camaraderie of the hospital. And a place like Yale-New Haven Hospital is full of such smart people. You stop in the hallway and you always learn something just by talking. I miss that. This [life as a writer] is a lonely life.

The change has to do with the increase in scientific distance, with the increase in objectivity, with the increase in instrumentation. For the first 15 years of my practice, so much of diagnosis depended on talking with a patient, putting your hands on a patient. The techniques were relatively straightforward technologies. They had to do with x-rays, electrocardiograms, things of this nature, biopsies. But gradually, imaging took over -- CT scans, MRIs, needle samples. We learned to do more with blood tests than we had been able to do before. And the drive in medical diagnosis was for complete scientific objectivity. So it was no longer so much of an art as it had been before.

Doctors, I think, rely far less nowadays on this personal thing, which had to do with talking and touching and beginning to understand someone and what that person's life was like. This has done phenomenal harm to the so-called doctor-patient relationship. Also, at a hospital like ours, we treat complex diseases. Complex diseases usually require teams, and the role of the individual physician is lessened.

A lot of the kind of medicine we were so proud of until the late '70s, the early '80s, was intuitive. That was the art of medicine. But who knows what intuitive means? I think the quality we call "intuitive" comes from increasing experience, increasing sensitivity and the workings of the unconscious mind. You're learning things all the time without realizing you're learning them. Any experienced physician will tell you that within a few minutes of starting a conversation with a patient, he or she can already get some pretty strong idea of at least how sick that person is, what might be required to make the diagnosis, and, not infrequently, have made the diagnosis already.

One of the things students in the International Health Program at the School of Medicine say they like about the program is the chance it offers them to do more diagnoses without the benefit of technology. Do you think there is a hunger for more hands-on medicine?

No doubt about it. It's tremendous fun. It's very exciting. You're there on your own.

It's exactly like being a detective. When you reconstruct a disease process, it is also somewhat like writing a play. The disease has a plot to it and there is scenery and there are costumes and the actor looks a certain way. You reconstruct all of this in your mind. The other thing is that from the moment the patient says the very first word, you're trying to figure out how this disease process evolved.

Schools are soon going to be teaching most surgery with virtual reality techniques. On the one hand, it's a wonderful teaching tool. On the other hand, surgery is a tactile exercise. Your fingertips tell you so much. No matter how well they can construct the inside of a body in virtual reality, it's certainly not going to be the same as touching it, unless they can figure out some technology to do that. Who knows what they will manage to do?

The patient gains and the patient loses. It's a trade-off. I think he gains in diagnostic accuracy. I don't think technology's accuracy is enormously better than ours, but it's definitely better. And the patient certainly gains in time spent. My generation of doctors didn't know as much as young people do today. But I think there's a loss of this sense of a doctor and a patient going on a journey together.

As a medical historian, you write about procedures that years ago were considered state of the art. In looking at today's medicine, in what areas do you think we might be seen, 20 years from now, as the most primitive?

In certain ways we are most primitive exactly where we are most advanced. What I mean by that is this: To me the sine qua non of Western scientific medicine is the ability to see. The ability to see differentiates Western medicine from any other form of healing. We demand of ourselves that even if we can't directly see what it is, we know what is going on within that organ or cell. We don't truck in terms of energies that can't be measured or interactions between organs that there is no proof of. So when a Western doctor makes a diagnosis, it essentially tells you exactly what is happening within the organs, the tissues and finally, the cells. So what is the ultimate in that diagnostic capability? It's the image, being able to show it instead of just imagining it.

As time has gone on, we have gotten better and better at showing what is more and more minute. We are just on the verge of vast improvements in a new technique called functional MRI, which can actually study chemical reactions of the body. So, imaging has made huge advances. But 20 years from now the imaging of the year 2000 will seem primitive because the field is going to move so fast. I'm going to predict that there will come a time probably within 25 years when patients will be placed in chambers and very minute cellular interactions will be detected by these various imaging techniques to make a complete diagnosis. The reason I am so confident about this is that it is starting to happen. Imaging is all the rage. Also, it is the ultimate goal in Western medicine to see what is happening.

Over the years I have met certain surgeons who are unlucky. Not many. People whose skills I've admired, whose intellect I've admired, and yet everything just goes wrong for them. ... They end up having complications [with their patients] that other people never get. They are constantly being sent patients whose diseases are at such a risky state that it's very hard to get them through and then they carry on their shoulders the burden of not being able to be therapeutically successful. Luck is a very, very difficult concept. What I was talking about more in the book was what I call "dumb luck," individual cases where some fortuitous event occurs that will get you out of a difficult spot. That problem that if you had to rely only on your ability and your knowledge and your experience you wouldn't get out of.

I think our lives are very, very random. One of the most difficult things to explain to patients with serious diseases is the randomness of disease. Everybody who gets very sick, especially with malignant diseases, asks, "Why me?" And the more I study diseases, especially since writing "How We Die," the more I have been convinced of the random shots of our lives. Genetic predisposition, environment, life experiences -- all of them combine randomly in each of us. We like to think in this day of self determination that we can control so much, but there's a limit to what you control. Bolts do come out of the blue. Bricks do fall on our heads, figuratively. I think one does everything possible to control everything that one can. But there's a lot of luck in this world, bad luck and good luck, and you can't spend a lot of time obsessing about what you did wrong when things go badly. By the same token, you can't let your head swell too much when things go very right.

-- By Jacqueline Weaver

T H I S

Bulletin Home

Why don't we start with the last question first. What are you working on now?

How did you come to write "The Mysteries Within?" Did it evolve from "How We Die?"

Is there much more interest today in human anatomy, in medicine, in how the body works?

So we are coming out of a time when people didn't want to know about the body in detail?

Which is your favorite organ -- the heart, the spleen, the stomach, the liver or the uterus?

Do you still practice medicine, or are you a full-time writer?

Do you miss surgery?

How have doctor-patient relationships changed?

What do you mean?

How much of practicing medicine is intuitive?

Like being a detective?

What do you think about replacing the traditional anatomy course, working on cadavers, with software programs?

How does the new technology affect patient care?

You talk in your latest book about luck. How has luck played a role in your professional and personal life?

W E E K ' S

W E E K ' S S T O R I E S

S T O R I E S![]()

New Michelin Guide spotlights Yale

New Michelin Guide spotlights Yale![]()

![]()

Fleury to be new dean of engineering

Fleury to be new dean of engineering![]()

![]()

Discovery may yield new therapies for liver disease

Discovery may yield new therapies for liver disease![]()

![]()

'The Mysteries Within' details noted surgeon's fascination with the body

'The Mysteries Within' details noted surgeon's fascination with the body![]()

![]()

Students devote their summer to public service in New Haven

Students devote their summer to public service in New Haven![]()

![]()

Emeritus Faculty

Emeritus Faculty![]()

![]()

Venus Williams will return to defend Pilot Pen crown

Venus Williams will return to defend Pilot Pen crown![]()

![]()

Study reveals why most schizophrenics are heavy smokers

Study reveals why most schizophrenics are heavy smokers![]()

![]()

E. Turan Onat, 75, specialist in engineering materials, dies

E. Turan Onat, 75, specialist in engineering materials, dies![]()

![]()

New center to host talks on U.S. parks

New center to host talks on U.S. parks![]()

![]()

Course to explore formation of spirituality in children

Course to explore formation of spirituality in children![]()

![]()

Winning Smiles: A Photo Essay

Winning Smiles: A Photo Essay![]()

![]()

Campus Notes

Campus Notes![]()

![]()

In the News

In the News![]()

|

| Visiting on Campus

Visiting on Campus |

| Calendar of Events

Calendar of Events |

| Bulletin Board

Bulletin Board![]()

Classified Ads |

| Search Archives

Search Archives |

| Production Schedule

Production Schedule |

| Bulletin Staff

Bulletin Staff![]()

Public Affairs Home |

| News Releases

News Releases |

| E-Mail Us

E-Mail Us |

| Yale Home Page

Yale Home Page