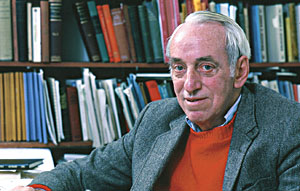

James Tobin, winner of the 1981 Nobel Prize in economics, an honored professor at the University and one of the most

influential economists of his time, died March 11 at the age of 84.

The Sterling Professor Emeritus of Economics, Mr. Tobin was described by fellow Nobel laureate Paul Samuelson as "the archetype of a late 20th-century American scholar."

Professor Tobin had a distinguished teaching career spanning over 50 years, during which he made many outstanding contributions to economic theory.

President Richard C. Levin, the Frederick William Beinecke Professor of Economics, said: "Jim Tobin was among the most gifted and inspiring of his generation of economists. He possessed a rare clarity of mind and a deep moral sensibility. We who had the privilege to study with him would all agree that he was our greatest teacher."

Professor Tobin's fundamental concern was how economic policies affected people's lives. He believed that the federal government could use fiscal and monetary measures to benefit society.

William Brainard, the Arthur M. Okun Professor of Economics at Yale, a colleague and former student of Professor Tobin, said of a theory course Tobin taught: "It was abstract, but Jim never let you lose sight that the ultimate reason for studying theory was to make the world a better place."

James Tobin was born on March 5, 1918, in Champaign, Illinois, to a social worker mother and a father who became sports information director for the University of Illinois. He grew into adulthood during the Depression. In a 1981 interview with The New York Times, he cited his experience growing up in that era as his inspiration for studying economics. "It was easy to get interested in economics," he said, "because it was clear that the things that were wrong with the world had a lot to do with economics."

He won an academic scholarship to Harvard in 1935. There Mr. Tobin was introduced to the theories of the British economist John Maynard Keynes, whose then newly published book "The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money," advocating governmental intervention in the economy, came to influence the Yale economist's later academic research, including the work for which he received the Nobel Prize.

Mr. Tobin earned his three academic degrees from Harvard: his bachelor's in 1939; his master's the following year; and his Ph.D. in 1947, after wartime service.

In 1941 he went to work for the U.S. government in Washington, D.C., first in the Office of Price Administration and then with the Civilian Supply and War Production Board. Mr. Tobin enlisted in the Navy following the attack on Pearl Harbor. At the Navy officers training program at Columbia University, he met the future Secretary of State Cyrus R. Vance and the novelist Herman Wouk.

In his book, "The Caine Mutiny," Wouk immortalized his friend as the character Tobit, a midshipman with "a mind like a sponge ... ahead of the field by a spacious percentage."

After serving four years on the U.S.S. Kearny in the Atlantic and Mediterranean, ending his naval duty as executive officer of the ship, Mr. Tobin returned to Harvard to earn his doctorate. He stayed at Harvard as a junior fellow until 1950. That year he received his academic appointment at Yale as associate professor of economics. He was promoted to the rank of full professor five years later, and was named the Sterling Professor of Economics in 1957.

Professor Tobin's early research provided theoretical underpinnings for Keynesian macroeconomic theory, and led to the modern theory of portfolio choice and asset pricing.

In the early 1950s, Professor Tobin served as an editor at two prestigious economic journals, Econometrica and the Review of Economic Studies. In 1955, he was recognized by the American Economic Association's John Bates Clark Medal as the "American economist under the age of forty ... judged to have made a significant contribution to economic thought and knowledge." The same year he became director of the Cowles Foundation for Research in Economics, an organization dedicated to connecting mathematical and statistical studies to economics, which had just moved from the University of Chicago to Yale.

In 1960, Professor Tobin's work came to the attention of President-elect John F. Kennedy, and won him a place on the President's Council of Economic Advisers. When tapped for this post, Professor Tobin initially resisted, identifying himself as "an ivory tower economist." "That's all right, professor," Kennedy replied, "I am what you might call an ivory tower president."

The report that Professor Tobin wrote with the two other members of the Council, Kermit Gordon and Walter Heller, was a seminal statement of political and economic policy that was to dominate public discourse for many decades and is still hotly disputed today. Council members recommended goals of full employment, greater competition and stiffer enforcement of anti-trust legislation. The report also advocated increased investment in science and technology, industrial and commercial infrastructure, and education and training.

After a year-and-a-half in the Kennedy ,administration, Professor Tobin returned to Yale and to the concerns of the academy. At the same time, he became increasingly vocal in the political arena, taking strong issue with the presidential campaign of Barry Goldwater and writing articles in magazines of political opinion, such as Daedalus and The New Republic. In the 1960s he espoused the "negative income tax" as a method for achieving income redistribution while maintaining incentives to work. In 1972 he joined George S. McGovern's campaign for the presidency as an adviser on economic reform.

In 1981, Professor Tobin received the highest honor awarded in his field, the Nobel Memorial Prize for economic science. When presenting the Yale economist the prize, the Royal Swedish Academy of Science cited his "creative and extensive work on the analysis of financial markets and their relations to expenditure decisions, employment, production and prices."

The academy also noted: "Unlike many other theorists in the field, Tobin does not confine his analysis solely to money, but considers the entire range of assets and debts. ... Few economic researchers of today could be said to have gained so many followers or exerted such influence on contemporary research."

In addition, the academy recognized the importance of Professor Tobin's "portfolio theory," which -- summed up in his own words -- is simply, "Don't put your eggs in one basket."

Although Professor Tobin formally retired in 1988, he continued to work at the highest level. Among the awards he received are the Eckstein Prize of the Eastern Economic Association, 1988; Grand Cordon, Order of The Sacred Treasure, Japan, 1988; Centennial Medal, Harvard University Graduate School, 1989; and Medal of the Presidency of the Italian Republic, 1993. The James Tobin Professorship of Economics was established in his honor at Yale in 1994.

The author of dozens of books and hundreds of articles, Professor Tobin continued writing until the end of his life. His recent books include "Money, Credit and Capital," 1997; "Full Employment and Growth," 1996; and "Essays in Economics, Vol. IV, Theory and Policy," 1996.

Professor Tobin's ideas continue to play a prominent role in political discourse. The "Tobin tax," his 1971 proposal for a foreign currency exchange tax aimed at stabilizing exchange rates and reducing global financial speculation, has become a rallying cry of the anti-globalization movement, which, as a free trade advocate, he strongly disavowed.

He is survived by his wife of 55 years, the former Elizabeth Fay Ringo; their four children, Margaret, Michael, Hugh and Roger; and three grandchildren.

Memorial gifts may be made to the James Tobin Fund for Graduate Study in Economics, in care of the President's Office, Yale University.

An announcement of a memorial service will be made at a later date.

T H I S W E E K ' S

W E E K ' S S T O R I E S

S T O R I E S

Soros Fellowships for New Americans

Soros Fellowships for New Americans

American Academy of Arts and Letters Awards

American Academy of Arts and Letters Awards

Poll reveals how 'deliberative' discussion can shift public opinion

Poll reveals how 'deliberative' discussion can shift public opinion

Men's basketball team concludes record-setting season

Men's basketball team concludes record-setting season

Nobel Prize-winning economist James Tobin dies at 84

Nobel Prize-winning economist James Tobin dies at 84

In Focus: Molecular, Cellular & Developmental Biology

In Focus: Molecular, Cellular & Developmental Biology

Silviculturalist Oliver named to Pinchot chair

Silviculturalist Oliver named to Pinchot chair

Berkeley and Yale Divinity Schools renew their affiliation

Berkeley and Yale Divinity Schools renew their affiliation

Erikson and Timmons awarded DeVane Medals

Erikson and Timmons awarded DeVane Medals

Alumnus describes how engineers 'cook up' new products

Alumnus describes how engineers 'cook up' new products

Haller and Henrich reappointed as college masters

Haller and Henrich reappointed as college masters

Levin visits with alumni across the nation and beyond

Levin visits with alumni across the nation and beyond

Exhibit documents volunteers' role in Spanish Civil War

Exhibit documents volunteers' role in Spanish Civil War

Event explores role of faith, gender in fighting AIDS in Africa

Event explores role of faith, gender in fighting AIDS in Africa

Team develops rules for identifying unseen problems in elderly

Team develops rules for identifying unseen problems in elderly

Researcher's index assesses mortality risk for elderly patients

Researcher's index assesses mortality risk for elderly patients

Drama School actors gang up for 'Serious Money'

Drama School actors gang up for 'Serious Money'

Students' new adaptation of 'The Trial' takes to the stage

Students' new adaptation of 'The Trial' takes to the stage

Work of architect on view in 'Zaha Hadid Laboratory'

Work of architect on view in 'Zaha Hadid Laboratory'

Conference will examine the changing notions of beauty

Conference will examine the changing notions of beauty

Panel looks at ethical issues nurses face

Panel looks at ethical issues nurses face

Yale Books in Brief

Yale Books in Brief

Campus Notes

Campus Notes

Bulletin Home |

| Visiting on Campus

Visiting on Campus |

| Calendar of Events

Calendar of Events |

| In the News

In the News |

| Bulletin Board

Bulletin Board

Yale Scoreboard |

| Classified Ads

Classified Ads |

| Search Archives

Search Archives |

| Deadlines

Deadlines

Bulletin Staff |

| Public Affairs Home

Public Affairs Home |

| News Releases

News Releases |

| E-Mail Us

E-Mail Us |

| Yale Home Page

Yale Home Page

March 15, 2002

March 15, 2002 Volume 30, Number 22

Volume 30, Number 22 Two-Week Issue

Two-Week Issue

W E E K ' S

W E E K ' S S T O R I E S

S T O R I E S![]()

Soros Fellowships for New Americans

Soros Fellowships for New Americans

![]()

![]()

American Academy of Arts and Letters Awards

American Academy of Arts and Letters Awards![]()

![]()

Poll reveals how 'deliberative' discussion can shift public opinion

Poll reveals how 'deliberative' discussion can shift public opinion

![]()

![]()

Men's basketball team concludes record-setting season

Men's basketball team concludes record-setting season![]()

![]()

Nobel Prize-winning economist James Tobin dies at 84

Nobel Prize-winning economist James Tobin dies at 84![]()

![]()

In Focus: Molecular, Cellular & Developmental Biology

In Focus: Molecular, Cellular & Developmental Biology![]()

![]()

Silviculturalist Oliver named to Pinchot chair

Silviculturalist Oliver named to Pinchot chair![]()

![]()

Berkeley and Yale Divinity Schools renew their affiliation

Berkeley and Yale Divinity Schools renew their affiliation![]()

![]()

Erikson and Timmons awarded DeVane Medals

Erikson and Timmons awarded DeVane Medals![]()

![]()

Alumnus describes how engineers 'cook up' new products

Alumnus describes how engineers 'cook up' new products![]()

![]()

Haller and Henrich reappointed as college masters

Haller and Henrich reappointed as college masters![]()

![]()

Levin visits with alumni across the nation and beyond

Levin visits with alumni across the nation and beyond![]()

![]()

Exhibit documents volunteers' role in Spanish Civil War

Exhibit documents volunteers' role in Spanish Civil War![]()

![]()

Event explores role of faith, gender in fighting AIDS in Africa

Event explores role of faith, gender in fighting AIDS in Africa ![]()

![]()

Team develops rules for identifying unseen problems in elderly

Team develops rules for identifying unseen problems in elderly![]()

![]()

Researcher's index assesses mortality risk for elderly patients

Researcher's index assesses mortality risk for elderly patients![]()

![]()

Drama School actors gang up for 'Serious Money'

Drama School actors gang up for 'Serious Money'![]()

![]()

Students' new adaptation of 'The Trial' takes to the stage

Students' new adaptation of 'The Trial' takes to the stage![]()

![]()

Work of architect on view in 'Zaha Hadid Laboratory'

Work of architect on view in 'Zaha Hadid Laboratory'![]()

![]()

Conference will examine the changing notions of beauty

Conference will examine the changing notions of beauty![]()

![]()

Panel looks at ethical issues nurses face

Panel looks at ethical issues nurses face![]()

![]()

Yale Books in Brief

Yale Books in Brief![]()

![]()

Campus Notes

Campus Notes![]()

|

| Visiting on Campus

Visiting on Campus |

| Calendar of Events

Calendar of Events |

| In the News

In the News |

| Bulletin Board

Bulletin Board![]()

|

| Classified Ads

Classified Ads |

| Search Archives

Search Archives |

| Deadlines

Deadlines![]()

|

| Public Affairs Home

Public Affairs Home |

| News Releases

News Releases |

| E-Mail Us

E-Mail Us |

| Yale Home Page

Yale Home Page