side in city-wide festival

From one end of the campus to another -- and working in fields as varied as psychiatry, engineering, law and information technology -- there are Yale staff members who also spend their time creating art.

Nearly a dozen of these artists are participants in this year's City-Wide Open Studios, a celebration of local artistic talent hosted by the New Haven non-profit organization Artspace. Yale is a lead sponsor of the arts festival, which takes place over three weekends at various venues in the city and beyond.

The final weekend of the event, Oct. 24-26, will feature artists who will exhibit their works at 25 Science Park, in what is known as the Alternative Space. Since City-Wide Open Studios was started six years ago, artists who do not have their own studios have been invited to create exhibitions and installations in an empty New Haven building, which they transform into a festive bazaar and arts showplace. (The first two weekends of City-Wide Open Studios featured artists working in their own studios or in studios at Erector Square in Fair Haven.) A main exhibition featuring a representative work from all City-Wide Open Studios artists is open daily, noon-5 p.m., through Oct. 29 at Artspace, 50 Orange St.

Following are brief profiles of four staff members who will show their creations at Science Park. Other Yale faculty or staff who have been featured in City-Wide Open Studios are Forrest William Barnett of the School of Management; Terry Dagradi of Information Technology Services' Medical Media Services; Natalie Gillihan of the Yale University Art Gallery; Clinton Arthur Jukkala of the School of Art; Jo Kremer Sadowitz of the Department of Psychiatry; and Christopher Mir and Jaime Ursic of the Yale University Art Gallery. Numerous Yale students are also showing their work, and other University staff members are lending their support to the festival in a myriad of other ways.

On Oct. 24, the Yale School of Art will host Open Studios featuring students' works at Hammond Hall, 14 Mansfield St., 6-9 p.m., and Holcombe T. Greene Jr. Hall, 1156 Chapel St., 5-8 p.m.

The Alternative Space studios at Science Park will be open 4-8 p.m. on Friday, and noon-5 p.m. on Saturday and Sunday. A $5 donation is suggested. For further information on the arts festival, call (203) 227-2709.

In works that utilize and sometimes combine such techniques as printmaking, weaving and Xerox transfers, Howard el-Yasin hopes to inspire viewers of his art to examine their own beliefs and perceptions.

In fact, stirring thought about -- and sometimes challenging -- cultural traditions and beliefs is far more important to the artist than "creating works that are pretty," says el-Yasin, the manager of the McDougal Center's Blue Dog Café.

The lynching of African Americans and human violence are some of the subjects he explores through the imagery in his art, which he also creates using materials he has found in the homes of relatives and along his travels.

A bat that he found in the basement of his grandparents' home, for example, served as a centerpiece in a mixed-media work on the theme of battery.

"When I look at objects I think about narratives I can create that might have personal meaning but also some universal or historical meaning," says el-Yasin. "The bat, for me, evoked images of battery. Everyone has a story or two in their family about battery, and this work was meant to conjure up images of that."

Likewise, a collection of S&H Green Stamps, commonly collected by shoppers in the 1960s, became his material for a woven art piece that he based on a traditional weaving pattern in African-American culture.

"I had heard wonderful stories about S&H Green Stamps from my grandmother and mother," says the artist. "My mother used to collect them and cash them in to buy clothing, and I found them an interesting subject to work with because of how they became a commodity, and because of the personal family relationships to these stamps."

More recently, el-Yasin has incorporated weaving into his artistic creations, which, he says, is an unconventional technique for male artists in the Western world.

"I want to explore things that are not traditionally acceptable for men to explore as a way to overturn the idea of domestication," explains the Yale staff member.

Some his artworks feature texts from books or magazines in the public domain, and he will often print, draw or paint over these texts -- using red paint, for example, to evoke blood in artworks depicting violence in human experience.

"I am interested in work that elicits visceral emotion," says el-Yasin.

The subject of lynching was inspired by the haunting images evoked in el-Yasin when hearing his grandparents, who grew up in the South, tell stories about racial violence.

"I want my works that explore lynching to be haunting images because that is what they are," says el-Yasin. "While that kind of work may not be traditionally acceptable, I think we have to have the courage to look at the past in order to create a better future."

Art has been a central facet in el-Yasin's life for many years. For more than 15 years he served as the manager of the Yale University Art Gallery's Museum Shop. About a decade ago, he began studying printmaking at the Creative Arts Workshop in New Haven, and he has also taken some art classes at Wesleyan University.

It is only more recently, however, that el-Yasin has begun more seriously to devote time to his artistic pursuits. He says his job at the McDougal Center, which he began three months ago after leaving the Yale Art Gallery, is more conducive to artistic creation.

"I think sometimes you need to be away from art in order to create art," he explains.

The artist recently became a member of the newly founded Arts + Literature Laboratory Gallery on Edwards Street in New Haven -- more commonly known as the ALL Gallery -- and his work has been featured in several exhibitions there. He is exhibiting his work for the first time in City-Wide Open Studios.

The unconventional aspects of el-Yasin's work have also fueled interesting discussions for the artist.

"Some people may not find my work visually acceptable or appealing, but I find that when I talk about it, they look at it differently. I think people sometimes look at a piece and expect it to mimic a part of American culture they can identify with. But my aim, in part, is to turn some of those cultural expectations upside down."

Howard el-Yasin will exhibit his works in space #361 at 25 Science Park.

In a laboratory in the Becton Engineering and Applied Science Center, Maria Gherasimova discovered that an object that is imperfect as science is something that she finds beautiful as art.

Gherasimova, a postdoctoral associate in electrical engineering, grows crystals in the laboratory as part of a team effort by engineers to develop more energy-efficient semiconductors, which are used in most modern electronic gadgets.

As part of this project, her goal is to create in a reactor crystalline films that are flawless. She judges their perfection or imperfection by looking at the films -- which are about a hundred times thinner than paper -- under a Nikon microscope that can magnify viewed objects up to 1,000 times. If the surface appears nearly completely smooth under the microscope, the crystal she has grown passes the test for perfection.

The crystals with flaws are useless to her scientific work, but their undesired features are fascinating to the engineer, who sees in their microscopic patterns other worlds, mimicking natural landscapes and the cosmic scenery of outer space.

Gherasimova, who earned her Ph.D. in engineering from Yale last year and now works in the laboratory of Professor Jung Han, takes digital pictures of the complex worlds that draw her attention under the microscope. These images will form the bulk of her show at Science Park, where she will be a first-time City-Wide Open Studios exhibitor.

"I have always been interested in the aesthetic aspect of what I'm doing," says Gherasimova. "I think the defects in the crystals are beautiful, and I turned them into art."

The Yale engineer also takes realistic photographs of buildings and scenery in the New Haven area, and is particularly interested in old and abandoned urban factories and industrial centers.

"I am fascinated by the process of the post-industrial conversion of our society," she explains, acknowledging that through her own research, she plays a role in creating some of the cutting-edge technology that helps bring about that transformation.

"I am working on a new technology and seeing the old technology fade away," Gherasimova says.

A native of Russia who grew up in a scientific community in Siberia, Gherasimova immigrated to New Haven when she was 20 years old and earned her undergraduate degree in physics from Southern Connecticut State University. She has long been interested in observing the changes that take place in her home city.

"New Haven is a waterfront city, and yet visitors don't know it's on the coast because of its transformation over time," Gherisomova says. "America is a very industrial society -- very cutting-edge -- and we continually see old industries dying out. Factories that used to be on the water are no longer functioning."

Such defunct factories are as aesthetically beautiful to the engineer as her defective crystals, says Gherasimova, adding that for both, "their beauty emerges as their usefulness disappears."

Her photographs include images of old brick buildings that once housed now-closed industries, such as the former Smoothie undergarment factory in New Haven, which Gherasimova photographed before its recent conversion into apartments. She also enjoys walking along the city's River Street in the Fair Haven neighborhood where, she says, there are still signs and remnants of the city's coastal history.

"I think some of the urban brick buildings are the most beautiful architecture that America has produced," says Gherasimova, an admirer of the work of photographer Berenice Abbott, who documented the early 20th-century transformation of New York City.

While the photographer says that she finds little aesthetic appeal in more modern industrial parks, she predicts that she will discover beauty in them "as they fall into decay."

Gherasimova admits that she feels some ambivalence about the societal revolutions brought on by technological advances. However, she says, "There is no way to stop the advance of technology, and I don't think we should try."

In fact, she admits, technological progress is the substance of her own art.

"My goal as an artist is to connect dying industry with new technology from an aesthetic point of view," comments Gherasimova, noting that her digital images of defective crystals are one example of how she attempts to fulfill that aspiration.

Adds the photographer: "It is just amazing to me that outer space can exist under a microscope."

Maria Gherasimova will exhibit her work in space # 373 at 25 Science Park.

When he perches his Rolleiflex twin-lens camera in an isolated spot in the woods, Rob Rocke is prepared for the unexpected.

A nude human body merges with and mimics the gnarled branches of a mostly leafless tree; nymphs and gnomes frolic in the forest; and nearly camouflaged arms and hands fan out in opposite directions across a split-in-two tree trunk in a selection of his black-and-white photographs, which can evoke what Rocke describes as "a fairy tale or dream-like quality."

Often his images are a series of scenes that Rocke -- who is also an actor -- created as a kind of artistic or dramatic performance.

A computer support specialist with Information Technology Services, Rocke has acted with local community theater groups and, most recently, at the Long Wharf Theatre, where he appeared in last year's production of Eugene O'Neill's "Mourning Becomes Electra."

Many of his photographs feature nude human forms in natural settings such as the woods, or other "surreal" environments that he finds interesting as backdrops for performance art. These images, Rocke says, are inspired by his appreciation of the human body as an artistic form and by his interest in depicting the body or its parts "interacting with or playing with the environment." He emphasizes, however, that while creating such art, he is careful not to be offensive.

Many of his photographs are self-portraits created by using a 10-second self-timer, a device he remembers from family gatherings in his youth and for which he feels a nostalgic attachment because of the serendipitous nature of such timed picture-taking.

"It really suits me to have this balance between having a lot of control over the basic image and this totally random element," says the photographer. "I get all ready to go and I lean into [the frame] as far as I can and I push the shutter and whatever happens, happens. You have to shoot a lot because inevitably there are a lot of mistakes: There will be one image of me falling as I climb into a tree, for example, or one with just my hand in it, but then I'll get one or two or five prints that are just amazing."

His works also include a series of photographs from Holyland in Waterbury, Connecticut. The now-closed tourist attraction -- identifiable by its huge hilltop cross -- was both a mecca for the religiously devout and a popular social hang-out. He has also taken stand-alone images of objects from times past -- ranging from photos of the former Smoothie undergarment factory in New Haven where City-Wide Open Studios was held three years ago to a coin-operated children's ride in the form of a boar.

"I have a certain soft spot for the vintage," explains the Yale staff member.

Rocke, who holds a master's degree in music from Yale, says his technically oriented job at the University (he services the computers of some 125 administrative staff members on the Central Campus) provides a diversion from his more creative pursuits.

Now in his fifth year as a City-Wide Open Studios' artist, Rocke is serving as a coordinator of the Alternative Space and a bike tour leader for this year's event. He relishes talking with visitors about the "sometimes surprising" ways they have been touched by his art, noting that he appreciates that every viewer "brings his or her own story" to his photographs.

A student of New Haven photographer Harold Shapiro at the Creative Arts Workshop, Rocke is currently perfecting his skill at digital printing at Yale's Digital Media Center for the Arts. With his camera, he plans to continue his exploration of scene, form and self-portraiture.

"I really get lost doing this work and that's the ideal of any art or sport or job ... It's a bit timeless; I go out and spend hours and don't really realize it, and in the most beautiful way, I'm in my own little world."

"I really love nature and the woods and hopefully, if nothing else, [my work] is a huge testament to that," he continues. "I mean, just being out there shooting is half the catharsis of the whole thing."

Rob Rocke will show his work in space #222 at 25 Science Park.

Living a fast-paced life that involves frequent train rides back and forth between New Haven and New York City, Christina Olson Spiesel looks for the artistic in the commonplace, often while she is in motion.

She finds it in the fragments that make up the passing scenery in her vision: the light that comes in a train window and falls on a fellow passenger's foot; the symbols painted on a sidewalk by utility workers or the carvings of an anonymous person on a wooden park bench; or the signs, advertisements and political graffiti that she passes in subway stations or on walks through city streets.

Using her digital camera, she captures these quickly observed images with the eye of a painter -- which is how she first began creating art a couple of decades ago.

Today, Spiesel finds the camera better suited to her busy life as a senior research scholar at the Law School and an adjunct professor at both the New York Law School and Quinnipiac University School of Law. Nevertheless, she thinks of herself, first and foremost, as a painter.

"I'm a painter who is using a camera right now," explains Spiesel. "While running around, the camera is a studio I can carry with me. I capture a lot of little pieces of time, taking my painterly interest right smack into the camera.

"My photography emphasizes the strokes of the hand and doesn't make a smooth rendition of the world," she continues. "I take photographs of detritus from human presence in the environment, and since my pictures are often of moving things, the images are jittery. I have no idea what I am going to get in print. They are like a painting -- showing people out there marking the world just as I make marks on a canvas."

Spiesel's work as an artist is inextricably linked to her career in the field of law and to her long-held interest in computer technology and its implications for society. At Yale, her research explores the intersection of law and technology and technology and ethics, among other topics. Her teaching includes a law course that examines the persuasive nature of visual images at play in the law, training students to think critically about their use and possible misuse.

A major focus of her exhibition in City-Wide Open Studios will be mid-1990s photographs Spiesel took of the demolition of some of the manufacturing buildings that made up the former Winchester Repeating Arms Company and of more recent reconstruction of the Science Park site.

"I'm interested in the themes of destruction, construction and deconstruction," notes Spiesel. "Once I knew that Science Park would be the Alternative Space for City-Wide Open Studios, I decided that it would be great to show some of my earlier images of the site depicting the rubble of both tearing down and building up." This theme has been particularly significant to her since the 9/11 tragedy, after which she spent days grieving with and consoling her students at New York Law School, which is located near the former World Trade Center site.

One of the founders of Artspace -- the non-profit arts organization in New Haven that sponsors City-Wide Open Studios -- Spiesel has exhibited her paintings, digital photographs and mixed-media works at the annual arts festival since its inception six years ago. For her, the opportunity to talk about her art with the public is the highlight of her involvement.

"When you show your work in a gallery, most of the people who come are friends and family, and you talk about everything but your art," says Spiesel. "At City-Wide Open Studios, people just walk through, filled with curiosity and feeling free to ask questions. The format allows for much more conversation about what you do."

Spiesel also appreciates having the chance to show her work in a different New Haven venue each year, which allows her to be creative while she installs her work in the temporary spaces.

"I like to think of the process as being like musical improvisation," says the Yale staff member. "It isn't like the jazz isn't rehearsed, because it is rehearsed. But in a moment of performance, one incorporates things he or she doesn't anticipate and things just take fire."

Christina Olson Spiesel will show her work in space #231 at 25 Science Park.

T H I S

Lynchings and physical battery are among the subjects that Howard el-Yasin explores in his mixed media artworks. The Yale staff member says he has introduced artistic materials and techniques that are not traditionally used by male artists in the Western world. The untitled mixed media work at left is among his creations.

Howard el-Yasin: Challenging cultural perceptions

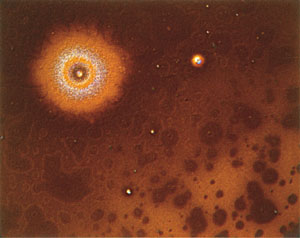

To Maria Gherasimova, the patterns of flawed crystals look like natural landscapes or outer space. Her digital photographs of microscopic worlds include this untitled work.

Maria Gherasimova: Finding worlds under a microscope

Human and natural forms

are joined in many of Rob Rocke's images, which include the photo at left, titled "Awakening."

Rob Rocke: Merging art and performance

The tearing down and re-building of Science Park is the focus of Christina Olson Spiesel's exhibition of digital photos, which include this interior image of a demolished building.

Christina Spiesel: Capturing slices of life

-- By Susan Gonzalez

W E E K ' S

W E E K ' S S T O R I E S

S T O R I E S![]()

Pharmacology department marks opening of new wing

Pharmacology department marks opening of new wing![]()

![]()

Revolution in biology leads department onto a new path

Revolution in biology leads department onto a new path![]()

![]()

Yale celebrates 300th anniversary of renowned Russian city

Yale celebrates 300th anniversary of renowned Russian city

![]()

![]()

Staff reveal their artistic side in city-wide festival

Staff reveal their artistic side in city-wide festival

![]()

![]()

Evidence of devastating volcano found in tortoises' genes

Evidence of devastating volcano found in tortoises' genes

![]()

![]()

Team discovers possible drug target for metastatic cancer

Team discovers possible drug target for metastatic cancer

![]()

![]()

Despite adversity, Chinese researcher brings his love of science to Yale

Despite adversity, Chinese researcher brings his love of science to Yale

![]()

![]()

Freshman Addresses

Freshman Addresses

![]()

School of Management is honored for its mission . . .

School of Management is honored for its mission . . .

![]()

![]()

Half of children studied choose toys over sweets . . .

Half of children studied choose toys over sweets . . .

![]()

![]()

Series will examine issues of illness and health in the African diaspora

Series will examine issues of illness and health in the African diaspora

![]()

![]()

Seminars and exhibits honor contributions of Yale ecologist

Seminars and exhibits honor contributions of Yale ecologist

![]()

![]()

'Writing in Circles' is theme of this year's Dwight Terry Lectures

'Writing in Circles' is theme of this year's Dwight Terry Lectures

![]()

![]()

Infants' ability to predict actions may emerge as early as 12 months

Infants' ability to predict actions may emerge as early as 12 months

![]()

![]()

Sessions to explore prospects, potential of biotechnology

Sessions to explore prospects, potential of biotechnology

![]()

![]()

Russian Singing Angels to perform in benefit concert on campus

Russian Singing Angels to perform in benefit concert on campus

![]()

![]()

Memorial Service

Memorial Service

![]()

![]()

Campus Notes

Campus Notes

![]()

Bulletin Home |

| Visiting on Campus

Visiting on Campus |

| Calendar of Events

Calendar of Events |

| In the News

In the News![]()

Bulletin Board |

| Classified Ads

Classified Ads |

| Search Archives

Search Archives |

| Deadlines

Deadlines![]()

Bulletin Staff |

| Public Affairs

Public Affairs |

| News Releases

News Releases |

| E-Mail Us

E-Mail Us |

| Yale Home

Yale Home