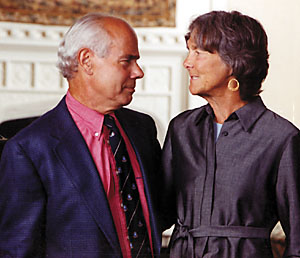

| Dr. Vincent Marchesi is shown here with his wife, Dr. Sally Marchesi, who began showing signs of Alzheimer's disease in her 40s. |

The first signs, like the slow and steady progression of the disease itself, were subtle -- burned coffee pots and checks returned in the mail because bills had been paid multiple times.

"It was easy to attribute these mishaps to the hectic life of a woman, a dynamo, who was raising six children and working full time," says Dr. Vincent Marchesi, director of the Boyer Center for Molecular Medicine and the Anthony N. Brady Professor of Pathology. He was speaking about Dr. Sally Marchesi, his wife and a former colleague in the Department of Pathology. She was in her late 40s at the time.

One day several years later Marchesi was sitting in the back row of an auditorium listening to his wife lecture. The two were classmates in medical school and he knew her research better than anyone else did. "She was describing her work, but she wasn't describing it right," he says.

Soon after, she attended a professional dinner meeting in Washington, D.C., but did not realize until she returned home that she had been sitting at the wrong table with the wrong group of people. It was the last trip she took alone.

"A painfully revealing moment came the day when she was lecturing to Yale medical students," he says. "She stopped talking in mid-sentence, not knowing what to say next. As she later related to me, the students shuffled around, whispered to each other and eventually left the room, leaving her standing alone at the podium."

The Marchesis knew at that point, more than most couples would, that the problem was serious, probably life altering. "When you're in the business, you're more fearful of certain things than others," he says. "We never used the words 'Alzheimer's disease.'"

Sally Marchesi retired soon after at the age of 62 and stayed at home with her husband for two years. Without the strain of working, she seemed almost healthy, but eventually needed round-the-clock care and today is in a nursing home in Essex. The last time she was able to write her name was in 2001 when she signed a power of attorney. She can blink her eyes, but she can hardly speak, and she has difficulty walking.

During his wife's time at home Marchesi cut back his hours in the laboratory. In addition to caring for her, he read everything he could get his hands on about Alzheimer's disease -- even the supplements to the articles, something he had never had time to do before. Up until then he really didn't know much about the disease, but that is not the case today. He says he is amazed at his recall of details from hundreds of Alzheimer's studies.

First he talks about what is known. More than a century ago German neurologist Alois Alzheimer observed that plaque-like deposits of material were scattered throughout the brains of patients with advanced dementia. Scientists now know these plaques are composed of many elements, including small peptides generated by cleavage of a family of polypeptides known as amyloid precursor proteins (APPs). Two peptides that are widely regarded as major contributors to Alzheimer's disease are known as Ab peptides, A40 and A42. Both come from the segments of APP molecules.

This summer Marchesi published a Perspective article in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.0503181102) proposing a theory about the disease that, ironically, ties in very deeply with the research that has occupied him all of his life in the laboratory -- membrane proteins.

The widespread belief, he says, is that short peptides cut from the original amyloid proteins move into the spaces between cells in the central nervous system, where they come together in toxic aggregates that kill neurons and eventually form plaques. Marchesi suggests that some of these peptides stay associated with the cell membrane and exert their toxic effects by competing with and compromising the critical functions of proteins, how they naturally operate in the membrane. Marchesi says he can only speculate which of these functions might be affected, but many diverse actions vital for normal cell function could be affected.

"If these peptides, or fragments, are toxic to neurons because they concentrate within the cell membrane, we have to consider how neurons might be damaged, as well as entirely different approaches to therapy," Marchesi says.

What he firmly believes is that because the disease takes so long to progress, there must be some mechanism for slowing it down even further. He has no illusions about rescuing his wife, he says, but he does worry about his children and the millions of people it is estimated will develop Alzheimer's in the next few years.

"This disease is subtle. It's not like a bullet to the head, so this makes it more difficult," he says. "These cells are slowly -- very slowly -- not doing what they are supposed to do. So it is going to take a lot of sophistication to see what it is they are not doing. The nature of the process is slow, suggesting it's not going to be a weak link change. It's something that is slightly less effective or slightly more effective."

He says he came up with his hypotheses, parts of which other researchers already have proposed, by looking at the problem from an outsider's point of view. He is not applying for any grants related to Alzheimer's research and notes that he has no great ties to the field. But he believes that what he found during those two years of intensive reading, which continues to this day, is perhaps a new analysis of existing data. Scientists, many busy with their research and clinical and teaching commitments, rarely have time to read the current literature extensively and rely on colleagues and conferences to bring them up to speed, says Marchesi, adding that he considers this system of conveying information highlights to be a "hole" in the system.

Marchesi says that when he visits his wife, as he does weekly, he is struck by the similarity of symptoms exhibited by the patients with Alzheimer's. "There has to be some underlying problem because the people all look the same," he notes.

There are some intriguing studies, says the Yale pathologist. One found that women with arthritis had a lower incidence of Alzheimer's disease, so it was believed perhaps aspirin played a role in preventing the disease; a clinical trial did not prove that hypothesis. Two years ago studies of how anti-inflammatory medications affected the production of the beta peptides were encouraging, he notes, even though the doses were too high to give to humans. The clinical trial of a vaccination was stopped when many people developed encephalitis, but the work in this area is progressing further.

One of the problems of the Alzheimer's field is that we're looking at a very complex clinical problem as if it were largely an anatomical change in a tissue that's extremely inaccessible," says Marchesi. "Focusing on anatomy is like the 19th century in some ways. We're using anatomical markers such as plaques, tangles and neuronal loss, and trying to relate them to a very complex clinical course. It is really very complex -- you could easily say there are multiple different diseases going on here or that Alzheimer's is a series of different causes that could wind up having a common final pathway."

Another problem, he believes, is the nature of research itself where hundreds of scientists are working on the same problem but not sharing their findings every step of the way. This probably won't change, contends Marchesi.

For now his investigation continues, and he says he finds it therapeutic. He hopes to write an analytical paper encompassing all that he has read the last seven years. He also would like to organize a website for scientists researching the disease and provide all of them with the most up to date data.

The Marchesis' 45th medical school reunion is taking place at Yale next summer and he has agreed to be the social chair.

"That's something she would have done," he says.

-- By Jacqueline Weaver

T H I S

Wife's illness inspires pathologist

to investigate Alzheimer's W E E K ' S

W E E K ' S S T O R I E S

S T O R I E S![]()

School of Music receives gift of $100 million

School of Music receives gift of $100 million![]()

![]()

Class of 1954 Chemistry Building officially opened

Class of 1954 Chemistry Building officially opened![]()

![]()

IOM elects six from Yale

IOM elects six from Yale![]()

![]()

Yale will mark Veterans Day with salute to alumnus, flag rededication

Yale will mark Veterans Day with salute to alumnus, flag rededication![]()

![]()

University dedicates new Rudd Center for Food Policy & Obesity

University dedicates new Rudd Center for Food Policy & Obesity![]()

![]()

World Fellow Ibrahim honored for her human rights work in Nigeria

World Fellow Ibrahim honored for her human rights work in Nigeria![]()

![]()

Today's press fails to get 'to the bottom of things,' journalist says

Today's press fails to get 'to the bottom of things,' journalist says![]()

![]()

Activist calls for cohesive global response to international migration

Activist calls for cohesive global response to international migration![]()

![]()

Yale's matching gift to United Way supports school readiness

Yale's matching gift to United Way supports school readiness![]()

![]()

Wife's illness inspires pathologist to investigate Alzheimer's

Wife's illness inspires pathologist to investigate Alzheimer's![]()

![]()

Yale employee lends skills to help animals after the hurricane

Yale employee lends skills to help animals after the hurricane![]()

![]()

Doctor's career spent researching body's 'master chemical director'

Doctor's career spent researching body's 'master chemical director'![]()

![]()

MEDICAL CENTER NEWS

MEDICAL CENTER NEWS

Researchers find strong link between gene and dyslexia

Researchers find strong link between gene and dyslexia![]()

Study casts light on nature and spread of lethal brain diseaes

Study casts light on nature and spread of lethal brain diseaes![]()

Innovative therapy curbs effects of loss of oxygen during birth

Innovative therapy curbs effects of loss of oxygen during birth![]()

Study finds true reason that lymph nodes swell

Study finds true reason that lymph nodes swell![]()

Helping breast cancer patients find best online information . . .

Helping breast cancer patients find best online information . . .![]()

Merson speaks at launch of Russia's first M.P.H. program

Merson speaks at launch of Russia's first M.P.H. program![]()

![]()

New Yorker humorist to give public reading

New Yorker humorist to give public reading![]()

![]()

Veterans Day concert will feature School of Music alumni

Veterans Day concert will feature School of Music alumni![]()

![]()

Alumni innovators to discuss 'Entrepreneurship and the Law'

Alumni innovators to discuss 'Entrepreneurship and the Law'![]()

![]()

Vignery to conduct pharmaceutical research as Yale-Pfizer Visiting Fellow

Vignery to conduct pharmaceutical research as Yale-Pfizer Visiting Fellow![]()

![]()

Cell biologist Ira Mellman elected to prestigious EMBO

Cell biologist Ira Mellman elected to prestigious EMBO![]()

![]()

Richard Lalli to perform at benefit gala for the Neighborhood Music School

Richard Lalli to perform at benefit gala for the Neighborhood Music School![]()

Bulletin Home |

| Visiting on Campus

Visiting on Campus |

| Calendar of Events

Calendar of Events |

| In the News

In the News![]()

Bulletin Board |

| Classified Ads

Classified Ads |

| Search Archives

Search Archives |

| Deadlines

Deadlines![]()

Bulletin Staff |

| Public Affairs

Public Affairs |

| News Releases

News Releases |

| E-Mail Us

E-Mail Us |

| Yale Home

Yale Home