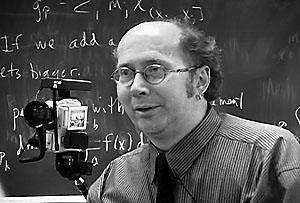

| This image from Dr. Gretchen Berland's film project "Rolling" show Ernie Wallengren coaching his son's basketball team. |

Videotaping

himself as part of Yale doctor Gretchen Berland’s documentary film project,

J. Galen Buckwalter describes how people have reacted to him during his 30

years of using a wheelchair, the result of a diving accident when he was 17. To see “Rolling” online, visit www.thirteen.org/rolling/experience/thefilm.

— By Susan Gonzalez

T H I S

‘Rolling’ offers honest, sometimes

shocking, look at life in a wheelchair

“Because most people can walk and run and climb, and because I can’t,

I’m defined as disabled,” says Buckwalter, a clinical psychologist

and vice president of eHarmony.com. “Not only am I defined as disabled,

I’m expected to feel and act disabled. Most people look at me and see what

I can’t do. For many years, I did the same. But what they don’t see

now is that I’m a survivor.”

Capturing what most people don’t see — what life is like for people

who use wheelchairs — was Berland’s goal in her award-winning film “Rolling,” which

recently aired on public television stations nationwide and was the subject of

a “Talk of the Nation” episode on National Public Radio in January.

Her interest in the subject is connected to another issue that has worried her

as a doctor: the gap between what physicians know about their patients’ lives

and how those lives are actually experienced on a daily basis.

To achieve her goal, Berland decided to do something a bit unconventional in

medical research. By mounting cameras onto the wheelchairs of the three subjects

in the film — including Buckwalter — the participants were able to

record in close detail the way the world appears to them. Berland and her research

associate, Tony Puyol, filmed only small sections of “Rolling” themselves,

and the Yale doctor occasionally narrates.

The other participants in “Rolling” are Vicki Elman, a middle-aged

divorced mother with multiple sclerosis, and Ernie Wallengren, a television writer

and producer with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), more commonly known as “Lou

Gehrig’s disease.” Over a two-year period, Buckwalter, Elman and

Wallengren recorded 200 hours of material, which Berland wove into edited narratives

to create a 72-minute documentary. The film was re-edited to 55 minutes for television.

In “Rolling,” viewers watch Wallengren as he loses physical

capabilities while his neurodegenerative disease progresses toward his eventual

death; they observe the frustrations of Elman as she deals with an insurance

company about a power wheelchair that is continually breaking down; and they

witness Buckwalter confronting the possibility of having to give up some of

the independence his manual wheelchair has afforded him due to intense shoulder

pain caused by wear-and-tear on his upper body.

“By allowing Galen, Vicki and Ernie to give us a visual, first-person perspective

of their lives, the storytelling is much more powerful,” says Berland.

Her film captures the everyday (and sometimes challenging) moments of the three participants’ lives — pulling

themselves from their wheelchairs into cars, navigating city streets, cooking,

coaching basketball and simply talking with family members — mixed with

intimate personal scenes — Buckwalter’s visit to his doctor in search

of a remedy for his pain; Elman being helped after falling while getting dressed;

and Wallengren, a husband and father of five, describing in a close-up shot of

himself his sadness over eventually becoming completely dependent on those he

loves and doesn’t want to burden.

In comments viewers have written on websites and in blogs, most acknowledge that “Rolling” can

be painful, and at times shocking, to watch. Berland has received hundreds of

e-mails from people, both disabled and not, who have seen the film, most of them

praising its honest portrayal of the lives of people with disabilities.

One scene of Elman, for example, shows her being dropped off at her house by

a public transportation service. Her wheelchair has stalled, but the driver says

it is against company policy to bring her into her home. Instead, he leaves Elman

on the sidewalk, 10 feet from her front door. Elman’s cell phone has no

service in that spot, so she can’t call anyone for help.

Elman films herself growing increasingly panicked as time passes. She begins

to cry in her helplessness. As the sky darkens, she resigns herself to the probability

that she will spend the night outside, in the cold.

“I wonder what Vicki Elman’s driver must have been thinking when

he drove away, knowing that he had left her stranded on the sidewalk,” says

Berland. “Shame on him.”

J. Galen Buckwalter is pictured here in a scene from "Rolling." In the film, Buckwalter discusses his identity as a person with a disability as well as his concerns about losing independence if forced to give up his manual wheelchair because of shoulder pain.

Buckwalter — writing in an article titled “The Good Patient” that

appeared in the Dec. 20, 2007 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine as

a companion piece to one by Berland about “Rolling” — says

that seeing his own footage in the doctor’s office makes him “cringe.” Watching

how he tries to please his physician makes him uncomfortable: He realizes that

his desire to be a “good patient” made him unable to communicate

the severity of his shoulder problem to his doctor.

“[T]he process of making ‘Rolling’ changed forever the expectations

I bring to encounters with physicians,” Buckwalter wrote. “Can video

cameras help other patients make themselves known to physicians in ways that

will improve the quality of health care interactions? Some of the scenes we filmed

are difficult to watch, but they happen. Through them, I see what I hope will

change. I have experienced what it can be like to engage with non-disabled persons

without trying to anticipate what they want me to be — and such memories

provide a cherished antidote to the feeling I re-experience each time I watch

that doctor’s visit unfold. Ultimately, at least for me, taking the camera

changed the equation.”

Berland, who was a film producer for public television before she attended medical

school, has long been familiar with the ability of film to tell personal stories

compellingly. While a medical student at Oregon Health Sciences University in

Portland, Oregon, she gave cameras to five teenagers to learn about their lives,

a project inspired by interviews she conducted with incarcerated teens. Later,

during her residency at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis,

she gave cameras to a dozen of her colleagues to film a “video diary” of

what happened while on call. That film, called “Cross-Cover,” has

since been used as a teaching tool in residency programs nationwide.

The idea for “Rolling” came to her when she attended a medical conference

as a Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholar and observed a participant who got

around using an electronic scooter. Berland, whose interests include participant-action

research and narrative medicine, wondered if she could do a qualitative study

that involved using a camera to explore the life of a person with a disability.

Her approach of using film to study health issues earned the Yale doctor the

reputation in medical circles of being non-traditional, a designation that might

have wreaked havoc on her career, especially in terms of getting research funding,

she says.

“We don’t really have a paradigm for what I do,” comments Berland,

whose film career included working for “Nova” at WGBH in Boston and

the “MacNeil/

Lehrer Newshour” in New York. “Everybody told me it was risky. I

don’t think it should replace all the other research methods we do, but

I do think that film can provide another viewpoint into many of the intractable

problems that we’ve been working on for a long time in the medical community.

It represents another way of trying to study the patient’s perspective.”

Berland’s non-mainstream approach to studying health problems has earned

her numerous accolades, including a MacArthur Fellowship in 2004. She has

used some of her $500,000 MacArthur grant to make “Rolling” available

for free for educational purposes.

“The MacArthur grant has made it intellectually, emotionally and financially

a lot easier to do my work,” says Berland. “When I got the call informing

me that I had won, [the person] from the MacArthur Foundation said, ‘We

believe in you. We believe ultimately in what you do.’ Those words are

worth more than any amount of money.”

She also credits Yale for its willingness to hire a less-conventional research

doctor.

“The University has been incredibly supportive of me,” says Berland,

who has been on the medical school faculty since 2001. The Yale University Art

Gallery is among the institutions or organizations that helped fund “Rolling,” which

was also screened on campus by the University’s Office on Disabilities.

Berland has other film projects in mind for the future, including one about traumatic

brain injury in American soldiers who have served in Iraq. As she ponders that

project, she is also responding to the tremendous interest “Rolling” has

generated since it was featured on PBS. In some locales where the documentary

aired, communities launched disability awareness programs or events in conjunction

with the film’s showing. Berland has received thousands of requests from

around the world for videotapes of “Rolling,” which several years

ago was named best documentary at the Independent Film Project conference for

works in progress, and was also chosen by the Independent Film Project for screening

at the European Film Market, held in conjunction with the Berlin Film Festival.

The film also won the Grand Jury Prize for best documentary at the Lake Placid

Film Festival.

Berland counts herself among the many people who report that “Rolling” has

changed their lives, especially in the way they now look at people who use wheelchairs.

“That Galen, Ernie and Vicki allowed us into their lives the way they did

is a privilege,” Berland says. “Seeing what they filmed has changed

how I see the world. One should be so lucky to have that kind of experience in

their lifetime.” W E E K ' S

W E E K ' S S T O R I E S

S T O R I E S![]()

Study: Farming is changing chemistry of Mississippi River

Study: Farming is changing chemistry of Mississippi River![]()

![]()

Pink is the new Yale blue for teams raising funds . . .

Pink is the new Yale blue for teams raising funds . . .![]()

![]()

‘Non-standard economist’ exploring motivations behind . . .

‘Non-standard economist’ exploring motivations behind . . .![]()

![]()

Other SOM behavior research studies explore consumers’ . . .

Other SOM behavior research studies explore consumers’ . . .![]()

![]()

Yale librarian and skater passes on her passion to local youngsters

Yale librarian and skater passes on her passion to local youngsters![]()

![]()

In new role at Yale, art conservator will exhance campus programs

In new role at Yale, art conservator will exhance campus programs![]()

![]()

Yale University Library starts the new year with staff changes

Yale University Library starts the new year with staff changes![]()

![]()

Drawings by European ‘masters’ are featured in gallery exhibit

Drawings by European ‘masters’ are featured in gallery exhibit![]()

![]()

Black History Month celebration features art, music and more

Black History Month celebration features art, music and more![]()

![]()

Yale Opera will present ‘Die Fledermaus’

Yale Opera will present ‘Die Fledermaus’![]()

![]()

Protection of cultural heritage is focus of ‘Iraq Beyond the Headlines’

Protection of cultural heritage is focus of ‘Iraq Beyond the Headlines’![]()

![]()

In new exhibition, architects envision ‘a future that could have been’

In new exhibition, architects envision ‘a future that could have been’![]()

![]()

Exhibition features unique gifts from around the globe

Exhibition features unique gifts from around the globe![]()

![]()

It takes two

It takes two![]()

![]()

First Yale BioHaven Entrepreneurship Seminar series event . . .

First Yale BioHaven Entrepreneurship Seminar series event . . .![]()

![]()

Memorial service will be held in Dwight Chapel

Memorial service will be held in Dwight Chapel![]()

![]()

Conversation on health care

Conversation on health care![]()

Bulletin Home |

| Visiting on Campus

Visiting on Campus |

| Calendar of Events

Calendar of Events |

| In the News

In the News![]()

Bulletin Board |

| Classified Ads

Classified Ads |

| Search Archives

Search Archives |

| Deadlines

Deadlines![]()

Bulletin Staff |

| Public Affairs

Public Affairs |

| News Releases

News Releases |

| E-Mail Us

E-Mail Us |

| Yale Home

Yale Home