In his newly released book, "Why Americans Hate Welfare: Race, Media and the Politics of Antipoverty Policy," Yale political scientist Martin Gilens explores the relationship between public attitudes about welfare and media misrepresentations of the nation's poor.

The book, published by the University of Chicago Press, expands on a study Gilens published two years ago that revealed that the news media has helped to create a misconception among Americans that poverty is primarily a "black problem." In the study, which received widespread media attention, Gilens reported that while African Americans comprise only 29 percent of the nation's poor, almost two-thirds of poor Americans shown on television news programs and in the major news magazines are black. This distorted portrait of the poor, he argues in his new book, has helped reinforce negative stereotypes about African Americans in general and about welfare recipients in particular.

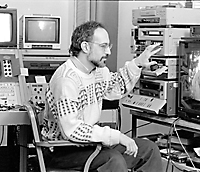

Gilens, who is an associate professor of political science and a fellow of the Institution for Social and Policy Studies, recently took the time to discuss "Why Americans Hate Welfare" with Yale Bulletin & Calendar staff writer Susan González. The following is an edited version of that conversation.

How did you first become interested in the subject of your book?

I think that how our country -- or any country -- deals with its poor people is both an important element of who we are as a people and what our values as a public are. I also care about the consequences of these attitudes and beliefs for those who are the least well off.

What are some of the general misconceptions Americans have about the poor and welfare recipients?

Surveys show that the misconception that blacks make up the largest segment of the poor is very widespread. In the book I argue that those misconceptions about the nature of the American poor stem largely from the misrepresentation of poverty in the mass media, and particularly in the news. In fact, in the news stories that I looked at on poverty, the racial composition of the poor is even more distorted than public perceptions are.

How do the poor and the non-poor view welfare differently?

The vast majority of Americans -- poor and non-poor alike -- are strongly supportive of the welfare state. By that I mean that they agree that government should spend more on education, child care, health care, the homeless and the poor. They are against cutting -- and in many cases favor increasing -- funding for most programs designed to help the poor, such as public housing, job training, Head Start, Medicaid, legal aid and so on. But they differ in their views about welfare.

Poor people are much more likely to say that welfare itself -- giving cash benefits to the working-age, able-bodied poor -- is a good way to address poverty, whereas the non-poor are much more likely to say that we should try to attack the causes of poverty rather than giving money to the poor in the form of welfare.

Does Americans' belief in self-sufficiency play a significant role in their opposition to welfare?

I think that the sort of rugged individualism that most people see as a central element of our country's political culture does heighten the importance placed on self-support by Americans from all economic strata.

But I argue that the public embraces a sort of bounded individualism, we think the first responsibility for an individual's welfare lies with himself or herself, but when help is needed it is then incumbent upon the government to supply that help. That is really the issue: whether the public believes that the need of most people on welfare is genuine, and a lot of Americans answer "no" to that.

The idea shared by many Americans that welfare recipients are undeserving -- how much do racial stereotypes play into this belief?

I think it's a big factor. First, we know that Americans exaggerate the extent to which poor people and welfare recipients are black. We also know that although racial attitudes have become more liberal across a variety of dimensions, many white Americans still believe that blacks are less committed to the work ethic than are whites. Finally,

In your book, you don't characterize this kind of stereotyping as racism. Do you not see it as that?

Well, racism is a concept with many possible definitions and a tremendous amount of social baggage. The kinds of attitudes I discuss, particularly the stereotypes of blacks, could very legitimately be termed racist stereotypes. But I don't find that a particularly useful characterization. For some whites, the belief that blacks are lazy reflects a broader antipathy toward African Americans, while for others it reflects a desire to justify whites' economic advantages. But most whites who think blacks are lazy and consequently want to cut back on welfare show considerable support for other programs which are just as strongly associated with black Americans.

For example, things like Head Start and job training are perceived as being more heavily black than is welfare, and yet those programs are overwhelmingly supported by white Americans. Even some specifically race-targeted programs, such as scholarships for blacks who do well in school, get very strong support among white Americans. The reason, I think, is that these programs are viewed as helping deserving Americans -- in this case deserving black Americans -- to better themselves. The fact that these programs get such high levels of support among whites suggests that it's not a sort of broad prejudice or racism toward blacks that explains the racial connection with welfare but rather a particular stereotype that welfare evokes.

You examined 40 years' worth of news coverage for your study, focusing on the major news magazines and the three major television news networks. What did that analysis reveal about the media's role in reinforcing racial stereotypes?

Americans' perceptions of the poor come not from their experiences of everyday life; they come from the images they get in the media. For example, the misconceptions about the racial composition of the poor are not limited to people living in areas where there are many poor blacks. Even if you look at places like Utah or North Dakota, where there are very few blacks among the poor, survey respondents will tell you that most poor Americans are black.

How have the white poor and the black poor been portrayed?

Before the 1960s, the poor in America were portrayed as overwhelmingly white. Indeed, the whole discourse on poverty from the early 1960s, starting with the Kennedy administration's antipoverty efforts, had a strong focus on rural white poverty-- in Appalachia in particular. The face of poverty changed dramatically around 1965, and by the late 1960s images of blacks dominated news coverage of poverty in both television coverage and news magazines. And that happened at the same time that the discourse on poverty became more negative.

When the War on Poverty began in 1964, news coverage was generally supportive. But by 1965 the news coverage on the War on Poverty was much more critical and the proportion of black faces much higher.

This pattern of associating black faces with negative stories on poverty was consistent across the 30-odd years of coverage that I looked at from that time on. In periods where news coverage tended to be most critical of the poor -- such as the early '70s when across the political spectrum people viewed welfare as a runaway mess that had to be reined in -- in that very critical period the proportion of blacks among pictures of the poor was extremely high; whereas in periods where coverage became more sympathetic, such as the recession of the early 1980s, I found very few black faces.

You also mention that blacks are underrepresented among subgroups of the poor for which Americans typically feel sympathy.

Yes, as you look across different subgroups of the poor, the most sympathetic groups -- such as the elderly poor, the working poor and the infirm -- have the smallest proportion of blacks in news coverage. On the other hand, the least sympathetic poverty subgroup -- the underclass -- those who have experienced intergenerational poverty, those who are involved in drug use and crime, etc. -- was illustrated exclusively with images of African Americans in the news magazines that I looked at. Blacks represent no more than 60 percent of the underclass no matter how you define that subgroup -- and by many definitions a smaller percentage -- and yet in the news we see that blacks completely dominated coverage of the underclass.

In the coverage you looked at, whites were pictured disproportionately in stories about the working poor and the rural poor?

Yes, and again, these tend to be neutral or positive stories.

How do you explain the media's misrepresentations of the black poor?

There are a number of things that might help to explain why blacks are overrepresented in general in media images of poverty. For example, the news bureaus are located in large cities. Also, poor blacks are more geographically concentrated than poor whites -- meaning that if you go to neighborhoods where the concentration of poor people is the highest, you will find a higher proportion of blacks living in those neighborhoods. Those things might play some role, but even so, if you look at poor people in large metropolitan areas in general, they are only slightly more likely to be black than in the country as a whole. So if news photographers or TV news crews made even a small effort, it's easy to find non-black poor people in most major American cities.

But this does not explain why whites are pictured in sympathetic stories about the poor and blacks dominate the images that accompany negative stories.

Exactly. It doesn't explain why there is this consistent pattern of associating photographs of the black poor with the least sympathetic groups of the poor and in the least sympathetic time periods in the public discourse about poverty. I think to explain that tendency you really have to look at the perceptions and stereotypes of the news people themselves.

In the book I talk about a story in which the text factually indicates that African Americans make up only about one-third of welfare recipients and yet in the pictures accompanying that very same story, 80 percent of the people on welfare are black. What's going on, I think, is that the attention to accuracy and the conscious process through which the text of the news story is constructed is simply not the same when it comes to photographs that accompany those stories. It's a largely subconscious process of selecting photographs and, therefore, the stereotypes and the preconceptions that the people involved may hold are free to be reflected in the images that are chosen.

How much do you think the media's misrepresentations affect public policy?

Those misrepresentations clearly have an impact on how the public thinks about poverty and what Americans -- at least what white Americans -- want to do about it. For example, on surveys I found that among white Americans, those who had more erroneous perceptions about the extent to which poor people are black also had more cynical attitudes toward people on welfare and were more likely to think welfare programs should be cut.

What solutions do you offer for helping to change people's perceptions to more accurately reflect the realities of the poor?

Well, if the misconceptions are largely shaped by the media, then the media has the power to change them. The question is: How can we get the media to more accurately and more fairly portray poor Americans in general and poor African Americans in particular? Doing photo audits of their photo coverage is one step that news organizations can take to ensure that they're not only being accurate in the news stories that they write but also in the kinds of images that accompany those stories, which I believe have a much more powerful impact on the public's perceptions than the text of the stories.

Another element which can help to shape the news products and the public's perceptions is to increase the number of minorities in the newsroom. While there seems to have been considerable progress along those lines over the past decades, minorities are still considerably underrepresented in major news organizations.

In spite of the false views the media has helped to perpetuate among Americans, you say that your book is not entirely negative. What positive message does it offer?

There are really two messages in the book. One is a "negative" one about why Americans hate welfare. But the other message is that despite their cynicism toward welfare recipients and the work ethic of black Americans, most people want to do more to help the poor; they want to do more to help deserving poor people who are white and deserving poor people who are black. So a lot of the book is about why Americans don't hate welfare, if you will.

For example, I argue that the economic self-interest of middle-class taxpayers and Americans' attraction to individualism are not important sources of opposition to welfare. These are factors that would tend to work against any government programs to fight poverty. But because opposition to welfare stems from the more narrow belief that most welfare recipients have chosen to live off the government rather than support themselves, anti-poverty programs that are not seen as open to abuse in this way receive strong support from the American public. In fact, an overwhelming majority of Americans share a genuine concern for helping poor people, and that, I think, is the book's optimistic message.

By Susan Gonzalez

T H I S

Bulletin Home

I show in the book that whites' views about black Americans, and in particular about whether or not blacks are committed to the work ethic, play a very strong role in shaping their attitudes about welfare -- a much stronger role than identical views about white Americans.

W E E K ' S

W E E K ' S S T O R I E S

S T O R I E S![]()

Commencement, 1999 Style

Commencement, 1999 Style

![]()

Facility to enhance strength in environmental sciences

Facility to enhance strength in environmental sciences

![]()

Guide again taps Yale as a 'must-see' attraction

Guide again taps Yale as a 'must-see' attraction

![]()

'Under My (Green) Thumb': Rolling Stones sideman talks about life . . .

'Under My (Green) Thumb': Rolling Stones sideman talks about life . . .

![]()

Summertime at Yale

Summertime at Yale

![]()

Endowed Professorships

Endowed Professorships

![]()

City-Wide Open Studios celebrates work of Yale and area artists

City-Wide Open Studios celebrates work of Yale and area artists

![]()

A Conversation About Welfare and the Media

A Conversation About Welfare and the Media

![]()

Eleven honored for strengthening town-gown ties

Eleven honored for strengthening town-gown ties

![]()

Special award, Jovin Fund commemorate student's good works

Special award, Jovin Fund commemorate student's good works

![]()

From design to construction, program gives architecture students . . .

From design to construction, program gives architecture students . . .

![]()

Graduate students cited for excellence in teaching

Graduate students cited for excellence in teaching

![]()

1999 Commencement Information

1999 Commencement Information

![]()

Beinecke exhibition celebrates the art of collecting books

Beinecke exhibition celebrates the art of collecting books

![]()

New line of Yale ties and scarves combine architectural elements . . .

New line of Yale ties and scarves combine architectural elements . . .

![]()

Studio classes again to highlight annual festival of arts and ideas

Studio classes again to highlight annual festival of arts and ideas

![]()

Project X Update

Project X Update

![]()

Leffell to speak about surgery for skin cancer

Leffell to speak about surgery for skin cancer

![]()

Kaplan honored for his work with children

Kaplan honored for his work with children

![]()

Guide shows motorists where to park downtown

Guide shows motorists where to park downtown

|

| Visiting on Campus

Visiting on Campus |

| Calendar of Events

Calendar of Events |

| Bulletin Board

Bulletin Board

Classified Ads |

| Search Archives

Search Archives |

| Production Schedule

Production Schedule |

| Bulletin Staff

Bulletin Staff

Public Affairs Home |

| News Releases

News Releases |

| E-Mail Us

E-Mail Us |

| Yale Home Page

Yale Home Page

| Political scientist Martin Gilens examined 40 years' worth of news stories -- both in the printed press and on television -- about poverty. He discovered that the media has distorted the realities about welfare recipients.

| |