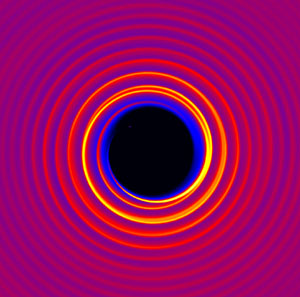

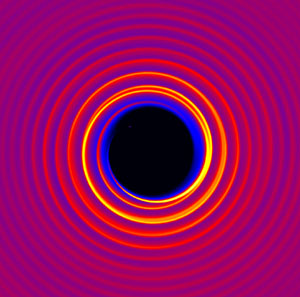

A slow dance lasting up to 10 million years between a super-massive black hole and a smaller one culminates in a violent outflow of energy, possibly powering the bright light known as a quasar, a Yale researcher and her collaborator have found.

"Ours is the first detailed calculation of how the merger of these two super-massive black holes proceeds," says Priyamvada Natarajan, assistant professor of astronomy. "This second phase, the merger, takes a few million years. And then there is a huge outflow of gas, and the quasar shines very brightly. It's a violent, very high energy event."

She and Philip Armitage, lead author of the article to be published in a forthcoming issue of the Astrophysical Journal Letters, and assistant professor at the University of Colorado, arrived at their conclusion via a theoretical, numerical calculation conducted on a supercomputer. The calculation allows the researchers to understand how the configuration would change over time.

Every galaxy has a massive black hole at its center that is more than one million times the mass of the sun. The black hole is detected, and its size determined, by the gravitational effect it has on the stars moving nearby. The larger the black hole, the stronger the pull of gravity and the faster the stars move.

A black hole gobbles up gas from what is known as an accretion disc, which is the disc of material that is spiraling around the black hole. En route to the black hole, the gas from the disc emits X-rays as its inner edge disappears into the gravitational field of the hole.

Energy released as gas falls into the black hole powers quasars, quasi-stellar objects that are very bright and inhabit extremely distant galaxies. What is not known, and what the researchers attempted to deduce, is how the quasars are likely to be turned on and off as a consequence of the merger of two super-massive black holes.

Once the two super-massive black holes become embedded in the accretion disc, they sit quietly at first, and then slowly their orbit shrinks, causing them to move closer together, Natarajan says.

"What is interesting during this phase is the critical separation stage when the black holes get close enough and all the gas trapped between them immediately rushes to the more massive black hole, leading to a brief increase in brightness coupled with an energetic outflow of gas at very high speeds," she says.

Natarajan says the next step in the research is to try to understand the final "hiss" when there is an outflow of energy following the merger of the black holes. "Our model predicts that both of those phenomena should happen simultaneously with the final merger of the black hole," she says.

-- By Jacqueline Weaver

T H I S W E E K ' S

W E E K ' S S T O R I E S

S T O R I E S

SOM competition to help nonprofits

SOM competition to help nonprofits

Student wins chance to meet Nobel laureates

Student wins chance to meet Nobel laureates

NYT reporter explains politics of science

NYT reporter explains politics of science

Astronomers suggest that 'slow dance' between black holes may power quasars

Astronomers suggest that 'slow dance' between black holes may power quasars

Levin discusses patent law in meetings with leaders

Levin discusses patent law in meetings with leaders

Burns' talks about Mark Twain and the American spirit

Burns' talks about Mark Twain and the American spirit

Innovations make the 'impractical' possible, says economist

Innovations make the 'impractical' possible, says economist

Renowned journalist Tom Friedman to visit as Poynter Fellow

Renowned journalist Tom Friedman to visit as Poynter Fellow

Talks by author Rushdie to explore changed nature of frontiers

Talks by author Rushdie to explore changed nature of frontiers

ENDOWED PROFESSORSHIPS

ENDOWED PROFESSORSHIPS

Aboard the Cultural Caravan

Aboard the Cultural Caravan

Exhibition honors memory of Dr. Donald Cohen

Exhibition honors memory of Dr. Donald Cohen

Conference to celebrate 'Langston Hughes and His World'

Conference to celebrate 'Langston Hughes and His World'

MEDICAL SCHOOL NEWS

MEDICAL SCHOOL NEWS

Master architects inspire students to design for the future

Master architects inspire students to design for the future

Conference looks at the 'faces' of Japanese cinema

Conference looks at the 'faces' of Japanese cinema

Library sponsoring program on Islamic civilization and identity

Library sponsoring program on Islamic civilization and identity

Campus Notes

Campus Notes

Bulletin Home |

| Visiting on Campus

Visiting on Campus |

| Calendar of Events

Calendar of Events |

| In the News

In the News |

| Bulletin Board

Bulletin Board

Yale Scoreboard |

| Classified Ads

Classified Ads |

| Search Archives

Search Archives |

| Deadlines

Deadlines

Bulletin Staff |

| Public Affairs Home

Public Affairs Home |

| News Releases

News Releases |

| E-Mail Us

E-Mail Us |

| Yale Home Page

Yale Home Page

February 15, 2002

February 15, 2002 Volume 30, Number 18

Volume 30, Number 18

W E E K ' S

W E E K ' S S T O R I E S

S T O R I E S![]()

SOM competition to help nonprofits

SOM competition to help nonprofits

![]()

![]()

Student wins chance to meet Nobel laureates

Student wins chance to meet Nobel laureates![]()

![]()

NYT reporter explains politics of science

NYT reporter explains politics of science

![]()

![]()

Astronomers suggest that 'slow dance' between black holes may power quasars

Astronomers suggest that 'slow dance' between black holes may power quasars![]()

![]()

Levin discusses patent law in meetings with leaders

Levin discusses patent law in meetings with leaders![]()

![]()

Burns' talks about Mark Twain and the American spirit

Burns' talks about Mark Twain and the American spirit![]()

![]()

Innovations make the 'impractical' possible, says economist

Innovations make the 'impractical' possible, says economist![]()

![]()

Renowned journalist Tom Friedman to visit as Poynter Fellow

Renowned journalist Tom Friedman to visit as Poynter Fellow![]()

![]()

Talks by author Rushdie to explore changed nature of frontiers

Talks by author Rushdie to explore changed nature of frontiers![]()

![]()

ENDOWED PROFESSORSHIPS

ENDOWED PROFESSORSHIPS Panel to probe questions surrounding Enron's collapse

Panel to probe questions surrounding Enron's collapse

![]()

Conference pays tribute to judge who was committed to racial justice

Conference pays tribute to judge who was committed to racial justice

![]()

Trustee Barrington D. Parker sworn in to federal court

Trustee Barrington D. Parker sworn in to federal court

![]()

![]()

Aboard the Cultural Caravan

Aboard the Cultural Caravan

![]()

![]()

Exhibition honors memory of Dr. Donald Cohen

Exhibition honors memory of Dr. Donald Cohen

![]()

![]()

Conference to celebrate 'Langston Hughes and His World'

Conference to celebrate 'Langston Hughes and His World'

![]()

![]()

MEDICAL SCHOOL NEWS

MEDICAL SCHOOL NEWS Grant supports research into the debilitating disease of narcolepsy

Grant supports research into the debilitating disease of narcolepsy

![]()

Dr. Robert Berliner dies; former medical school dean . . .

Dr. Robert Berliner dies; former medical school dean . . .

![]()

EPH researcher documents war's damaging effects

EPH researcher documents war's damaging effects

![]()

Crying by medical students may be a sign of their compassion

Crying by medical students may be a sign of their compassion

![]()

![]()

![]()

Master architects inspire students to design for the future

Master architects inspire students to design for the future

![]()

![]()

Conference looks at the 'faces' of Japanese cinema

Conference looks at the 'faces' of Japanese cinema

![]()

![]()

Library sponsoring program on Islamic civilization and identity

Library sponsoring program on Islamic civilization and identity

![]()

![]()

Campus Notes

Campus Notes

![]()

|

| Visiting on Campus

Visiting on Campus |

| Calendar of Events

Calendar of Events |

| In the News

In the News |

| Bulletin Board

Bulletin Board![]()

|

| Classified Ads

Classified Ads |

| Search Archives

Search Archives |

| Deadlines

Deadlines![]()

|

| Public Affairs Home

Public Affairs Home |

| News Releases

News Releases |

| E-Mail Us

E-Mail Us |

| Yale Home Page

Yale Home Page