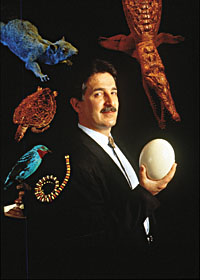

| Jacques Gauthier |

Professor Jacques Gauthier was watching CNN with his family in September when one of the announcements scrolling across the bottom of the television screen said a new dinosaur fossil had been discovered in China.

The new dinosaur's name, it said, was Incisivosaurus gauthieri.

"My son looked at me and said, 'It can't be named after you,'" recalls the Yale paleontologist. "I told him I thought maybe it was. He said, 'How did that happen? What, did you pay them, Dad?'"

Gauthier got his confirmation the following day: A team from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing had named a new species of dinosaur they discovered in honor of the Yale professor for his groundbreaking work on the evolutionary link between birds and dinosaurs.

"In this business, you cannot, of course, name a new discovery for yourself. But if you make a significant contribution to the area, someone else finding a new species can name it after you," explains Gauthier.

Incisivosaurus gauthieri lived 128 million years ago, during the early Cretaceous era, in what is now known as the Yixian Formation in northeastern China. It is one of the oldest and most primitive examples of the group of especially bird-like dinosaurs called oviraptors, which walked on two legs and had feathers, although they were flightless.

While previously discovered oviraptors sported beaks, Incisivosaurus gauthieri had buck teeth. In fact, it has been described by one commentator as "a cross between the Road Runner and Bugs Bunny." ("Some people say it looks like me," quips Gauthier.) Because the fossil's teeth are similar to those used by rodents for gnawing, scientists believe Incisivosaurus may have been a vegetarian, unlike other known oviraptors, which were carnivorous.

"It's a great specimen, a marvelously primitive one," says Gauthier. "By the time we see other oviraptor species, they're about 30 million years away from their actual connection to the bird line."

Gauthier is the latest in a line of Yale paleontologists -- from Yale Peabody Museum founder O.C. Marsh to emeritus professor John Ostrom -- who have sought to unravel the complicated evolutionary lineage between birds and dinosaurs, taking part in a debate that stretches back to the publication of Charles Darwin's "The Origin of Species."

"Birds don't look like anything, except for themselves," says Gauthier, noting that many scientists of the time were skeptical that "somehow, by coin flips of random mutation, birds were supposed to have evolved from other reptiles."

While Thomas Henry Huxley pointed out in the mid-1800s that there were similarities between the skeletons of birds and theropod (i.e., two-legged carnivorous dinosaurs such as Tyrannosaurus rex), other scientists argued that those similarities were due simply to the fact that both types of creatures walked on their hind legs.

In 1986, Gauthier weighed into the debate with a paper offering "the first phylogenetic analysis that addressed very specifically the question of where birds fit, in a very detailed sense, among dinosaurs. ....

"You're not there to actually see who begat who. So how do we reconstruct the genealogy of life?" the scientist says. "We have various methods that we've developed to do this. We've been able to test them by either building model systems or actually creating mini-evolutionary trees by taking bacteria-eating viruses and letting them reproduce a million generations in 24 hours. We know what we started with, and where we ended up, genealogically speaking." By periodically freezing samples of the various generations, "we can even make 'fossils' to examine the roles they might play in phylogeny reconstruction," says Gauthier.

"Tests of this sort enable us to see how well our methods recover the true pattern of parental ancestry and descent," he adds. "And we find they're pretty good. The idea was to apply these new methods to the age-old problem of where birds come from."

Using these methods, Gauthier proved that "among animals who lay eggs on land, the nearest living relatives of birds are crocodilians," he says.

"When people hear that, they go: 'Say what? Crocodiles don't look anything like birds.' But we're not talking about similarity; we're talking about common ancestry relationships," explains the scientist. "From any level of organization, from gene sequences to anatomical details to their behavior, crocodiles and birds share evolutionary novelties indicating that they are related. They both build nests and have their kids in their nests. They care for their young. They vocalize to attract mates and defend territories." They also, he notes, share distinctive features in their eyes, brain, heart and ear.

"Crocodiles and birds share these special resemblances that we use to reconstruct the history of life," asserts Gauthier. In fact, he adds, proving the link was "so easy ... that the question became 'What have we been fighting about?' Because the data had always been clear on this point: Birds are living dinosaurs."

In recent years, new discoveries by paleontologists have offered further proof of that link. "Now we have the feather impressions," says Gauthier. "It's one of those great triumphs. It's unbelievable how radically our view of the world has changed in such short order. Just think: T. rex with feathers!"

Today, the big debates in paleontological circles center on more specific issues of evolution and development -- exactly when dinosaurs became warm blooded, for example, or the exact genesis of flight -- "so the fight's moved on to another level," says Gauthier.

Complicating these debates is the fact that there are still huge gaps in the fossil record. "Nature never guaranteed she would give us all the evidence we needed to answer all the questions we might ask," he says.

Gauthier, who came to Yale seven years ago, has appointments in the Departments of Geology & Geophysics and Ecology & Evolutionary Biology. "Paleontology grew out of the geology business," he says, pointing out that the first fossils were found by geologists. "In modern times, paleontology has a much more biological bent. I come out of the biology world. I just deal with deep-time events."

As curator of vertebrate paleontology at ,Yale's Peabody Museum of Natural History, Gauthier also oversees a collection of hundreds of thousands of specimens, from prehistoric creatures to modern-day animals. The majority of the specimens are now housed in the new Class of 1954 Environmental Science Center adjacent to the Peabody. In addition to its other storage areas, the new facility includes a room for the frozen specimens used in DNA research.

"The collection is like a library," he notes. "But, instead of one version of this book, you may have many, because no two copies -- of organisms, in this instance -- are ever identical." Hundreds of scholars from around the world come to study the Peabody's collection, and the museum loans collection objects to researchers around the world.

"It's a big biodiversity resource center," adds Gauthier. "Everything we know about biodiversity is rooted in the specimens in these collections."

One thing that clearly emerges from the study of biodiversity, says the scientist, is "it's still the age of dinosaurs ... We write the textbooks, so we get to call it the Age of Mammals, but in terms of diversity, there's always been more dinosaurs than mammals for the past 180 million years.

"But they're all in the air now," he adds.

-- By LuAnn Bishop

T H I S

Fossil named in honor of Yale scientist W E E K ' S

W E E K ' S S T O R I E S

S T O R I E S![]()

Trustee launches book club for city youths

Trustee launches book club for city youths

![]()

![]()

Gilliss reappointed as dean of the School of Nursing

Gilliss reappointed as dean of the School of Nursing![]()

![]()

Fossil named in honor of Yale scientist

Fossil named in honor of Yale scientist![]()

![]()

Zedillo seeks to make globalization more 'inclusive'

Zedillo seeks to make globalization more 'inclusive'![]()

![]()

Grant supports Divinity School's participation in . . .

Grant supports Divinity School's participation in . . .![]()

![]()

Gift boosts collaboration in plant research

Gift boosts collaboration in plant research![]()

![]()

FORESTRY & ENVIRONMENTAL SCHOOL NEWS

FORESTRY & ENVIRONMENTAL SCHOOL NEWS Family's gift supports environmental studies major

Family's gift supports environmental studies major

![]()

Alumna endows fellowships for visiting conservationists

Alumna endows fellowships for visiting conservationists

![]()

Use of artificial ecosystems in research . . .

Use of artificial ecosystems in research . . .

![]()

![]()

In Focus: Yale Library

In Focus: Yale Library![]()

![]()

Olmos argues for more cultural pride but less racial division

Olmos argues for more cultural pride but less racial division![]()

![]()

Panel to explore relationship between media and . . .

Panel to explore relationship between media and . . .![]()

![]()

Dr. Orvan Hess, who helped develop fetal heart monitor, dies at 96

Dr. Orvan Hess, who helped develop fetal heart monitor, dies at 96![]()

![]()

Fun begets benefits for New Haven charities

Fun begets benefits for New Haven charities![]()

![]()

Model Student

Model Student![]()

![]()

Yale Books in Brief

Yale Books in Brief![]()

Bulletin Home |

| Visiting on Campus

Visiting on Campus |

| Calendar of Events

Calendar of Events |

| In the News

In the News![]()

Bulletin Board |

| Yale Scoreboard

Yale Scoreboard |

| Classified Ads

Classified Ads |

| Search Archives

Search Archives |

| Deadlines

Deadlines![]()

Bulletin Staff |

| Public Affairs Home

Public Affairs Home |

| News Releases

News Releases |

| E-Mail Us

E-Mail Us |

| Yale Home Page

Yale Home Page