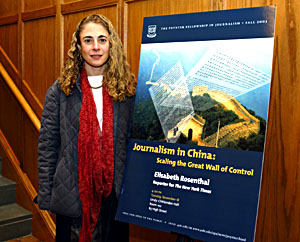

| New York Times reporter Elisabeth Rosenthal said covering the spread of SARS in China was made difficult by the government's refusal to acknowledge the epidemic. |

In a recent campus talk, New York Times reporter Elisabeth Rosenthal said her six-year assignment covering China was characterized by a steady increase in people's willingness to speak openly about their government and society.

"It's a different country," said Rosenthal, the year's first Poynter Fellow in Journalism, who discussed her work for The New York Times in China from 1997 to 2003 during a talk on Nov. 18.

When she first arrived in China, Rosenthal recalled, she would call sources from outside phones or arrange to meet them in hotel lobbies, and the people she interviewed were cautious about having their names appear in her stories. As the years passed, however, more and more people would call her at her office and speak on the record, she noted.

The journalist said she realized people were becoming more comfortable with speaking out when they would ask her why she was always at an outside phone when she called them, a practice they told her was no longer necessary.

"I was thinking: 'Wow! this place has really changed,'" she said of her sources' disappearing reticence.

She told the audience she was once approached by retired communist party members who complained that their housing and pensions were inadequate.

"These were real party stalwarts protesting," she said, adding that the retirees were willing to have their names attached to their complaints and eventually saw their issues addressed.

On another occasion, after a group of Chinese immigrants were found dead in Great Britain, she traveled to their home region to interview their families and neighbors. She did not have the government's permission, however, and was told to leave.

As she left, she recalled, her taxi driver asked her: "You're not going to let them push you around, are you?" Later, the taxi driver brought villagers to her at her hotel, and they were eager to speak on the record about the incident, said the journalist.

"They wanted me to see that, from their point of view, it made economic sense" to try to emigrate from China, she said.

Rosenthal noted that the growing sense of entitlement and expectation on the part of people with whom she came in contact was tempered by the difficulties she faced getting information and formal approvals for interviews from the government.

All journalists, for example, had difficulty covering the SARS epidemic because of the government's refusal to disclose the extent of the problem, she explained.

"We couldn't get into the military hospitals where the patients were," said Rosenthal, who worked as a medical doctor in an emergency room before joining The New York Times. She eventually interviewed a SARS patient leaving the hospital who said she became sick after attending a birthday party. The woman was angry at the government for failing to alert the public adequately, recalled the journalist.

"All seven people ended up in the hospital with SARS," Rosenthal said of the woman and her fellow party-goers.

She also noted that well-trained Chinese journalists were still handcuffed by the government's control of Chinese media. These reporters would tell her, "I can't write this, but you can," she said. "Ultimately, it's not their decision what goes in the newspaper."

The government, however, has welcomed more foreign journalists because it has realized that doing so will produce more positive stories about China for the rest of the world, said Rosenthal. China began to see that when an organization like The New York Times is allowed to have only one correspondent in China, he or she can only cover issues like human rights violations, she asserted, and that it is only when news organizations can add reporters that the additional staff can produce feature stories about Chinese society.

"The Chinese government realized the more the merrier," Rosenthal said.

As an addition to The New York Times staff in China, Rosenthal said, she found she had an abundance of stories to choose from that her solitary colleagues would not have had the time to pursue.

"It was like a field that hadn't been picked yet," she said.

-- By Tom Conroy

T H I S

Journalist reports greater willingness

to talk openly in China

W E E K ' S

W E E K ' S S T O R I E S

S T O R I E S![]()

Groundbreakings celebrate construction of new chemistry and

Groundbreakings celebrate construction of new chemistry and engineering buildings

engineering buildings Facility will support state-of-the-art research . . .

Facility will support state-of-the-art research . . .

![]()

Building will house new Department of Biomedical Engineering

Building will house new Department of Biomedical Engineering

![]()

![]()

Eire autobiography wins National Book Award

Eire autobiography wins National Book Award![]()

![]()

Dyslexia has been hurdle for scientist and 'Ironman' competitor

Dyslexia has been hurdle for scientist and 'Ironman' competitor![]()

![]()

ENDOWED PROFESSORSHIPS

ENDOWED PROFESSORSHIPS DiMaio is appointed as Von Zedtwitz Professor of Genetics

DiMaio is appointed as Von Zedtwitz Professor of Genetics

![]()

Hebert designated as C.N.H. Long Professor of Physiology

Hebert designated as C.N.H. Long Professor of Physiology

![]()

Somlo named as C.N.H. Long Professor in Internal Medicine

Somlo named as C.N.H. Long Professor in Internal Medicine![]()

![]()

In Focus: Center for Faith and Culture

In Focus: Center for Faith and Culture

![]()

![]()

Center aims to ease patients' anxiety about breast cancer

Center aims to ease patients' anxiety about breast cancer

![]()

![]()

Noël Valis' book awarded Modern Language Association prize

Noël Valis' book awarded Modern Language Association prize

![]()

![]()

Journalist reports greater willingness to talk openly in China

Journalist reports greater willingness to talk openly in China

![]()

![]()

City students to study Shakespeare in new Yale Rep program

City students to study Shakespeare in new Yale Rep program

![]()

![]()

Drama School to stage Wilder's play about 'First Family'

Drama School to stage Wilder's play about 'First Family'

![]()

![]()

Human evolution preserved in 'pseudogenes,' say scientists

Human evolution preserved in 'pseudogenes,' say scientists

![]()

![]()

Study: Mother's anti-depressant doesn't affect her nursing baby

Study: Mother's anti-depressant doesn't affect her nursing baby

![]()

![]()

Study shows spiritual belief and prayer can aid high-risk youth

Study shows spiritual belief and prayer can aid high-risk youth

![]()

![]()

The Fine Art of Shopping

The Fine Art of Shopping

![]()

![]()

'Sacred spaces' on campus featured in new calendar

'Sacred spaces' on campus featured in new calendar

![]()

![]()

Alternative Gift Market allows shoppers to help the world's poor

Alternative Gift Market allows shoppers to help the world's poor

![]()

![]()

Pepper Center awards will support research related to aging process

Pepper Center awards will support research related to aging process

![]()

![]()

Scientists to refine literacy game with support from grant

Scientists to refine literacy game with support from grant

![]()

![]()

Dr. Barry Kacinski dies; renowned for work in field of DNA repair

Dr. Barry Kacinski dies; renowned for work in field of DNA repair

![]()

![]()

Leon Clark dies; his work enhanced understanding of other cultures

Leon Clark dies; his work enhanced understanding of other cultures

![]()

![]()

Yale Books in Brief

Yale Books in Brief

![]()

![]()

Campus Notes

Campus Notes

![]()

Bulletin Home |

| Visiting on Campus

Visiting on Campus |

| Calendar of Events

Calendar of Events |

| In the News

In the News![]()

Bulletin Board |

| Classified Ads

Classified Ads |

| Search Archives

Search Archives |

| Deadlines

Deadlines![]()

Bulletin Staff |

| Public Affairs

Public Affairs |

| News Releases

News Releases |

| E-Mail Us

E-Mail Us |

| Yale Home

Yale Home