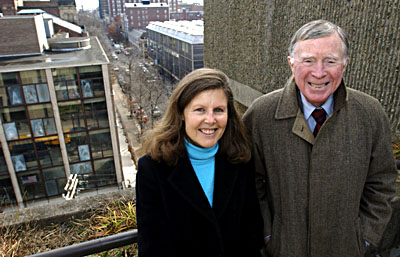

| Vincent Scully and his wife, Catherine Lynn, along with some of Scully's former students, have writen a new book describing Yale's architectural history. |

Vincent Scully, the Sterling Professor Emeritus of the History of Art, was recently recognized as one of the most influential and esteemed teachers of architectural history in our country with a National Medal of Art. (See story.)

A native of New Haven and alumnus of Yale, he has taught at his alma mater since 1947. Although retired, he continues to teach introductory courses in the history of art and the history of architecture, which receive rave reviews from the students who take them. The author of some 20 books and countless articles, he has recently co-authored -- with his wife, Catherine Lynn, and former students Erik Vogt and Paul Goldberger -- "Yale in New Haven: Architecture & Urbanism." (See related story.)

He recently sat down to talk with the Yale Bulletin & Calendar about some of his views of architecture generally and Yale's specifically. This is an edited version of that conversation.

Yale is a curiously fragmented campus. It's broken up into quadrangles, with very little coherence between them, with no fundamental central meeting place, except the Old Campus. The Old Campus is a wonderful space. On the other hand, one always feels a little bittersweet about it, because once there was the old Brick Row [the original Yale buildings of which only Connecticut Hall remains]. It was open to the Green, and townspeople could walk right through, so the relation of Yale to New Haven was very close and homogeneous. It was very noble.

Originally Yale was integrated with the Green. You can see the scenario where Yale would have taken over the Green. I think it's a good thing that Yale never did. But then there is that question about Yale making a conscious choice -- which it did -- of closing in on itself, so the Old Campus was turned into a quadrangle on the model of the British university, which is the last thing that New Haven's Puritan founders wanted. The city's nine-square plan is based on a reconstruction of Ezekiel's ideal city of refuge. John Davenport [the founder of the New Haven Colony] certainly without question regarded it as a New Jerusalem. That's why he called it New Haven. The last thing he would have wanted would be a model based on the English Anglican college system.

I remember once at a class reunion some years ago, I was talking about Yale architecture, and somebody asked me what my favorite building was. I tried to say that on a campus it isn't a question of individual buildings at all, which is the truth. In America now, the campus is one of the few places where you can make a whole environment. It's the relationship of all these things to each other -- and the set of community spaces that they make together -- that counts. It's not a question of individual buildings.

Well, the A&A Building is a complicated question. On the one hand, it's an unforgivable building -- with surfaces like that and so many complicated floor levels. On the other hand, it is beautifully sited. It's right on the axis of the sidewalk of Chapel Street. That whole sequence of buildings goes from the 19th century to that building, starting with Street Hall, then going to Egerton Swarthwout's building [the old Art Gallery], then to Louis Kahn's building [the current Yale Art Gallery], then to Paul Rudolph's [the A&A Building]. Rudolph's really climaxes the whole group. He very carefully made it the same height as Bingham Hall, way down at the corner of College Street. He really had the whole street in mind. I think the materials -- with the hammered surface -- are very questionable. It's sad, though, because it culminated that sort of heroic period in our culture. I think the A&A Building and Becton [Engineering and Applied Science Center] are two of remarkably few failures of Yale's modern buildings, and we have two great ones: the two buildings by Kahn, the Yale Art Gallery and the British Art Center.

I don't like to see any building torn down. Somebody said that one reason people want to save buildings is they're afraid that what they're going to get would be a lot worse. There was a period 20 or 30 years ago when that was clearly true. You knew that whatever you were going to get would be a lot worse. Now one isn't so sure. There are so many architects now that are very good at what we call contextual design. Better -- much better -- than they were 30 years ago. So I don't think in a way that there is quite the same emotional commitment to saving buildings. Now I find the issue a little less intense. On the other hand, I don't like to tear buildings down anyway. Just constitutionally, I think we should adjust to buildings. That's much more humane. We shouldn't demand that buildings fit our needs perfectly.

I suppose it's aesthetic really. Everything for me is aesthetic. It's all how it looks and makes me feel and so on. But I suppose the point is: I more and more think less about the individual buildings and more about their relationships. So I'm not so worried that one building may not work so well.

I was a confirmed Modernist, like everybody else, 30, 40, 50 years ago, when I was first teaching. And I think we did a lot of harm. I think we were very wrong.

We had very cataclysmic and simplistic ideas about city planning, for example. We really didn't have any respect for the traditional fabric of our cities, which is a miraculous development over centuries of time, much more important architecturally than the development of anything having to do with individual houses. Just the street, the curb, the grass strip, the trees, the sidewalks -- this is a marvelous urbanistic structure.

What I learned as time went on was that Modernism was very faulty, in view of what architecture was. That it was a simplistic view of architecture. It was predicated on an arbitrary aesthetic. It was totalitarian in its mode of thinking. Everybody had to do things one way. It was overly dominated by German determinism. The Germans were always talking about the Zeitgeist. You know the Zeitgeist was something that told us that we couldn't do things. All kinds of things we couldn't do -- couldn't build curved walls, for instance. As you get older you tend to think about these things, and you begin to realize: This is ridiculous; this is simplistic. It's not open-minded, and it's dangerously totalitarian in its mindset.

When I went to Italy on a Fulbright [Scholarship] in '51, I began to realize as I was taking pictures of buildings that I had to use more than one camera frame, because the buildings had to be viewed in relation to one another. I began to learn that everything is in relation to everything else. Then I worked on Greek temples and realized that they had to be seen in the landscape in which they were set, and that landscape is sacred as well. God is in the landscape, and God is in the building. And in that relationship is the typical Greek balance between what nature wills and what man wants. So I began to see everything in that relationship, and I began to realize that the Modernists were not doing so.

I wish I could believe so, but there is such a schism now in architecture between the great show-off performers who get those spectacular commissions, and the new urbanists who are making new towns. The new urbanists tend to despise the others, and we know the others absolutely hate the new urbanists. It is ideological in a way. They have opposite views of what architecture is all about, what you're supposed to do with it, what it's for.

Without any question. All the people who started it were Yale people: [Andres] Duany, Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, [Peter] Calthorpe, and so on.

The computer has liberated people to do things that would have literally been impossible for them to draw -- at least, it would have taken them too many man-hours to draw. There are these new shapes, which we used to call "free form" but we really had no idea how really free they could be until the computer. So design is in a way much more open to egregiously irregular kinds of shapes that you never expected to see in architecture, never used to see.

The public seems to be very interested in architecture now. And I think maybe for the wrong reasons. That avidity of the public for forms, new forms, any kind of forms, is not necessarily a very good thing for what might happen to architecture. Well, a large section of the public also backs new urbanism and reasonable planning, so maybe the public's interest simply reflects the split in architecture itself. I think, for example, the public reaction to the exposition of those six or eight entries for the World Trade Center was what you would expect.

In the past, architects spent most of their time taking care of buildings and repairing them and helping them along. You could be the architect of one cathedral for a whole lifetime. I think that's returning and that is part of preservation. One of the myths Modernism used to have was that you should be tough with buildings. Modern buildings age quickly, so you should have the guts to tear them down in 20 years, which I think is ridiculous. We expect our buildings to outlive us. It's very important. The continuity of what we build in cities goes back to the very first cities of mankind. The idea fundamentally is that architecture should be permanent.

Because of using materials in ways that were pushed by abstract considerations rather than fundamental views of how long they would last. Bad things happen: Kahn's Art Gallery has had to be almost completely rebuilt, whereas Swarthwout's much older building never had anything much wrong with it. It's protected. All the metal details are protected from moisture and that kind of thing, so they are meant to last, to last forever. The pre-Modernist architects weren't driven by abstract aesthetic and ideological conceptions. They just knew how to build. They loved to build. And the point should be made that those architects built better low-cost housing than the Modernists with all their pretensions to sociological purity.

-- By Dorie Baker

T H I S

Vincent Scully: On architecture

and its integral landscape

Are there parts of the Yale campus that you think work especially well and reflect what Yale is, and parts that are less successful?

Are there any Yale buildings of which you are particularly fond?

What about the Art & Architecture Building, which has been the focus of so much controversy over the years?

Do you think that buildings should be preserved at all costs, even the so-called failures?

Would you say, then, that your commitment to preservation is based more on social than aesthetic considerations?

Is it fair to say that you are generally opposed to Modernism?

Do you think we've gone beyond the age of "isms" when ideology dominated architecture?

Is it true that new urbanism grew out of Yale?

Have the "show off" designers created a new genre of architecture?

With the destruction of the World Trade Center and the debate over its replacement, architecture suddenly became part of regular public discourse. Is that something you think will be sustained?

When you talk about preservation and restoration and reusing old buildings, does that mean you see that as a new direction for the future?

Why do modern buildings fall apart so quickly?

W E E K ' S

W E E K ' S S T O R I E S

S T O R I E S![]()

Two professors win prestigious honors

Two professors win prestigious honors Library of Congress gives Pelikan Kluge Prize for lifetime achievements

Library of Congress gives Pelikan Kluge Prize for lifetime achievements

![]()

Scully is awarded National Medal of Arts at White House ceremony

Scully is awarded National Medal of Arts at White House ceremony![]()

![]()

Yale's newest Rhodes Scholars are Oxford-bound

Yale's newest Rhodes Scholars are Oxford-bound![]()

![]()

New program will promote Yale-Pfizer links

New program will promote Yale-Pfizer links![]()

![]()

The Art of Shopping

The Art of Shopping![]()

![]()

Market offers 'alternative' gifts that benefit world's needy

Market offers 'alternative' gifts that benefit world's needy![]()

![]()

Vincent Scully: On architecture and its integral landscape

Vincent Scully: On architecture and its integral landscape

![]()

![]()

Book explores Yale's architectural relationship with New Haven

Book explores Yale's architectural relationship with New Haven![]()

![]()

CNN anchor offers her perspective on presidential election

CNN anchor offers her perspective on presidential election

![]()

![]()

Neurosurgery advances rely on interdisciplinary focus, scientist says

Neurosurgery advances rely on interdisciplinary focus, scientist says

![]()

![]()

Study shows how different levels of alcohol impair areas of brain

Study shows how different levels of alcohol impair areas of brain

![]()

![]()

Conference pays tribute to scholar Robert Dahl

Conference pays tribute to scholar Robert Dahl

![]()

![]()

Viennese Vespers

Viennese Vespers![]()

![]()

Older persons with chronic illness have range of untreated . . .

Older persons with chronic illness have range of untreated . . .

![]()

![]()

Red Sox ovation

Red Sox ovation

![]()

![]()

Yale Books in Brief

Yale Books in Brief

![]()

![]()

Campus Notes

Campus Notes

![]()

Bulletin Home |

| Visiting on Campus

Visiting on Campus |

| Calendar of Events

Calendar of Events |

| In the News

In the News![]()

Bulletin Board |

| Classified Ads

Classified Ads |

| Search Archives

Search Archives |

| Deadlines

Deadlines![]()

Bulletin Staff |

| Public Affairs

Public Affairs |

| News Releases

News Releases |

| E-Mail Us

E-Mail Us |

| Yale Home

Yale Home