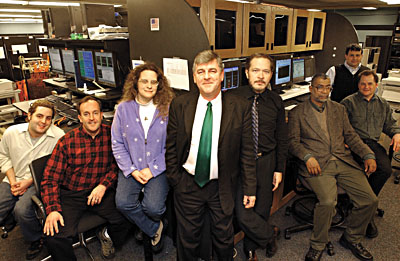

| Pictured are (from left) Jay Kubeck, computer operator; Bob Shields, shift coordinator at the Data Center; Lynna Jackson, manager of e-mail and calendaring services; Derek Harris, manager of production services for the Data Center; H. Morrow Long, Yale's information security officer; Richard Morris, University postmaster; John Coleman, senior systems administrator; and Fran Loehmann, systems programmer. |

ITS is boosting its arsenal against spam

We all know them -- those annoying (and sometimes nasty), unsolicited e-mails that greet us when we check our electronic mail each morning and then nag us throughout the day.

Some pronounce that a brother (or other family member or friend) is in pain, and then advertise a particular medication; others appear to come from a bank asking for verification of account information; and some curiously arrive under the simple heading "Re our appointment." Then there are the infamous pleas from strangers to assist in funneling money out of their country (usually a third-world nation) and, in the process, reap some financial benefits ourselves.

The list goes on, and the volume of these pestering e-mails is on the rise, according to Lynna Jackson, manager of e-mail and calendaring services for the University's Information Technology Services (ITS).

Yet, due to the ongoing efforts of Yale's Information Security Office -- part of ITS -- Yale faculty and staff receive only a fraction of the junk mail, otherwise known as "spam," that is intended for their e-mail inboxes, and more help is on the way.

Spam is any unwanted, unsolicited e-mail, usually of a commercial nature that is sent to a large number of recipients. But unlike the paper junk mail typically sent to homes, spam can be extremely risky or harmful -- which is why the Information Security Office makes every attempt to weed it out of the electronic mailboxes of Yale staff.

H. Morrow Long, the University's information security officer, notes that there are basically three types of spam: the "garden variety," mainly harmless e-mails that attempt to entice computer users to buy a product; "phishing," e-mails that fraudulently claim to be from a legitimate business (such as a bank) in order to scam recipients into providing personal information such as bank account, credit card or Social Security numbers, which can then be used for criminal purposes; and "malware," forms of malicious software such as viruses, trojan horses (programs that seem like useful software but actually damage computers) and worms (viruses that can replicate and transport across networks automatically, without action by computer users).

"While the average computer user sees all three kinds as one big annoyance, we make technical distinctions between them because we must be most aggressive in our efforts to filter out destructive viruses," says Long.

At Yale, e-mails come in through one of three providers: Central E-Mail Services, which serves some 20,000 computer users (most of the campus, including Yale College and the Graduate School); the ITS-Medical Center server, for the approximately 9,000 students, faculty and staff at the Schools of Medicine and Nursing; and the School of Management server, which provides e-mail services for that school's 700 individuals.

Yale's nearly 30,000 computer users are easy targets for spam, notes Jackson, because university networks and e-mail systems must be more open to the public than corporate and other business systems. Approximately a million-and-a-half e-mail messages come in to Yale on a typical day. Jackson and Long estimate that close to 50% of this mail is spam.

ITS currently controls spam on two levels: first through a University-wide tagging system and then through client-based filtering devices.

The first level of spam management occurs in the ITS Data Control Center at 155 Whitney Ave., where inbound messages for Yale faculty, students and staff arrive through the Central E-Mail gateways. There, e-mail that is easily identified as virus-infected (and damaging to Yale's entire computer infrastructure) is eliminated. Mail from known spam servers or which is suspected of being virus-infected has been automatically "tagged" by e-mail servers as it enters Yale's network, and later filtered. Since Jan. 26, this e-mail is being returned to sender. (For specific information on this new practice of bouncing back mail identified as spam, see www.spamhaus.org/.

The Data Control Center is manned by ITS staff 24 hours a day, seven days a week, with the exception of major holidays. When there is a big spike in incoming e-mails, an alarm goes off, alerting ITS to a possible bulk mailing of spam or virus-infected messages. Within minutes, Data Control staff members can determine the type of mail being received.

"An extra 10,000 messages a minute will cause this alarm to go off," says Long, "and when we determine the mail to be malicious, we work quickly to block it."

According to Jackson, ITS recently averted a virus outbreak in Yale computers just before the December holiday recess, when there was an influx of mail with the header "Merry Christmas!" The virus-infected mail was detected by ITS staff members just minutes after they noticed a significant spike in the volume of incoming e-mail, and "they immediately took steps to protect our e-mail infrastructure," says Jackson.

"In the few weeks since this outbreak started, Yale e-mail servers have deleted millions of these infected messages directed at the Yale gateway to the Internet," she adds, noting there were up to half a million of these coming in per day.

Central E-mail users can use the spam and virus filtering software that is available in the Central E-mail Account Management Tool website (https://config.mail.yale.

Additional spam control is also available through client-based filtering e-mail options on most modern e-mail clients (Eudora, Thunderbird, Outlook and more). With these options, individuals can "train" their local e-mail programs to identify spam. These programs automatically identify likely spam and move the e-mail to a separate, local "Junk" folder. Computer users then check this folder, moving into their inboxes anything that has been mistakenly classified as junk mail. In the meantime, they also tag junk e-mails that made it to their inboxes. Over time, the spam filtering software "learns" from the computer user what he or she generally considers as junk mail.

"With any of these programs, there are sometimes a number of 'false positives' -- mail that is misclassified as spam or a virus," says Jackson, noting that mistaken identifications occur most frequently with virus filters, which more aggressively attempt to tag suspect mail. However, she and Long note, no mail that is tagged as suspect through either Central E-Mail or client-based filtering software is automatically deleted unless it contains identifiable viruses that can cause mayhem to the community of Yale computer users.

"As with the U.S. Postal Service, the principle behind e-mail is to never lose a piece of mail -- to deliver it rain, sleet or snow," comments Long. "Our systems are organized to avoid losing mail; they either deliver it or return it to sender, but never drop it in between. All of these filtering programs abide by that principle."

Another filtering device identifies mail that contains non-American English words or symbols in the mail header. A significant number of spam e-mails arrive in foreign languages, says Jackson, noting that this filtering software is obviously not recommended for those on campus who communicate with individuals throughout the world as part of their work.

While ITS urges that all Yale users of web-based e-mail programs take advantage of the filtering software, they are not required to do so, Jackson and Long note.

"Yale is a diverse community, and there is a significant population on campus who want to receive any message that is sent to them," says Jackson. "In addition, what one person might define as spam may not be considered spam by another."

Long and Jackson point out that there are currently no foolproof spam and virus management programs; nevertheless, they note, e-mail filtering software has improved vastly of late.

"For the first time, we actually have a glimmer of hope that we can reduce the torrent of spam," comments Jackson.

ITS recently licensed another new product for the campus, called Spy Sweeper, which detects and eliminates Spyware and Adware -- software programs that covertly gather information through computer users' Internet connections, usually for advertising purposes. Some of this software is able to monitor the users' keystrokes, scan files on their hard drives and "snoop" other applications. While these applications run in the background, they take up a computer's memory and resources, and can thus be highly damaging to a person's computer system.

"Spyware and Adware are becoming a bigger problem, and you can unwittingly install it on your computer just by downloading things over the Internet," notes Long. "So we will shortly be offering and strongly promoting the Spy Sweeper software to check for and remove these more malicious programs."

Despite all these precautions, however, hackers and advertisers are adept at concocting new means to get around filtering and other software designed to remove unwanted mail and other programs.

"New scams come every day, and scammers are very good at what they do," says Jackson. "Because of this, I always tell people that if they are ever caught up in a scam, it isn't because they are foolish; it is because the scammers are so good. Some take great pleasure in tricking the smartest, brightest, most fastidious people. So if you are caught in one of their schemes, it isn't because something is wrong with you."

Jackson and Long note that there are some practical steps that all Yale computer users should employ to protect themselves and their work on Yale computers. (See related story.) Chief among these, they say, is for all Yale faculty, staff and students to know whom to contact for help when a problem does develop.

"Everyone on campus has access to a support provider, either within their own office or department or through one of our distributed support providers at their school or department," says Jackson. "Know who they are. Whether for help with enabling e-mail filtering tools or for other concerns about spam, they are the best resource."

-- By Susan Gonzalez

T H I S

In Focus: Information Technology Services

edu/account-tool/do-login). There, Yale faculty and staff can enable "Spam Management" and "Virus Quarantine" software on their individual mail accounts to filter out the previously tagged e-mail. Since July, these filters have been automatically set on the computers of all new faculty and staff. Working with other campus providers, ITS is now engaged in a project to significantly enhance these central filters for all who choose to use them. (More information on this project will be forthcoming from ITS.) These filters will deposit suspect mail in a special folder, which clients can then check periodically to make sure that no legitimate mail was incorrectly tagged as spam.

W E E K ' S

W E E K ' S S T O R I E S

S T O R I E S![]()

Center will promote study of customers

Center will promote study of customers![]()

![]()

Organist Martin Jean appointed new ISM director

Organist Martin Jean appointed new ISM director![]()

![]()

Yale scientists hailed for research on H20

Yale scientists hailed for research on H20![]()

![]()

In Focus: Information Technology Services

In Focus: Information Technology Services![]()

![]()

Guarding your computer (and yourself) against scam and spam

Guarding your computer (and yourself) against scam and spam![]()

![]()

ENDOWED PROFESSORSHIPS

ENDOWED PROFESSORSHIPS Alexander is appointed the Saden Professor

Alexander is appointed the Saden Professor![]()

Thomas named Williams Brothers Professor

Thomas named Williams Brothers Professor![]()

Clark designated Cullman Adjunct Professor

Clark designated Cullman Adjunct Professor![]()

![]()

To Do Justice

To Do Justice![]()

![]()

Exhibit explores life and work of 'Peter Pan' creator

Exhibit explores life and work of 'Peter Pan' creator![]()

![]()

Former NSF director named as Bass Environmental Scholar

Former NSF director named as Bass Environmental Scholar![]()

![]()

Event celebrates life and legacy of poet James Merrill

Event celebrates life and legacy of poet James Merrill![]()

![]()

Belgian illustrated books are focus of exhibit, symposium

Belgian illustrated books are focus of exhibit, symposium![]()

![]()

Noted historian of African slavery to give inaugural Davis Lecture

Noted historian of African slavery to give inaugural Davis Lecture![]()

![]()

Study: Marijuana bears same risks as smoking cigarettes

Study: Marijuana bears same risks as smoking cigarettes![]()

![]()

Grant will fund study of novel stroke treatment

Grant will fund study of novel stroke treatment![]()

![]()

Center for Faith and Culture launches new lecture series

Center for Faith and Culture launches new lecture series![]()

![]()

Seminar to explore affirmative action around the globe

Seminar to explore affirmative action around the globe![]()

![]()

Yale Entrepreneurial Society adds new biotechnology category . . .

Yale Entrepreneurial Society adds new biotechnology category . . .![]()

![]()

Grant will further researcher's work on . . .

Grant will further researcher's work on . . .![]()

![]()

Yale takes on Harvard in 'friendly' competition: a Blood Drive Challenge

Yale takes on Harvard in 'friendly' competition: a Blood Drive Challenge![]()

![]()

IN MEMORIAM

IN MEMORIAM Dr. Marshall Edelson, proponent of the 'therapeutic community'

Dr. Marshall Edelson, proponent of the 'therapeutic community'![]()

Irene Adams, office administrator for the Yale Boswell Editions

Irene Adams, office administrator for the Yale Boswell Editions![]()

![]()

PULSE features literary, artistic works with theme of medicine

PULSE features literary, artistic works with theme of medicine![]()

![]()

Yale Boooks in Brief

Yale Boooks in Brief![]()

![]()

Campus Notes

Campus Notes![]()

Bulletin Home |

| Visiting on Campus

Visiting on Campus |

| Calendar of Events

Calendar of Events |

| In the News

In the News![]()

Bulletin Board |

| Classified Ads

Classified Ads |

| Search Archives

Search Archives |

| Deadlines

Deadlines![]()

Bulletin Staff |

| Public Affairs

Public Affairs |

| News Releases

News Releases |

| E-Mail Us

E-Mail Us |

| Yale Home

Yale Home