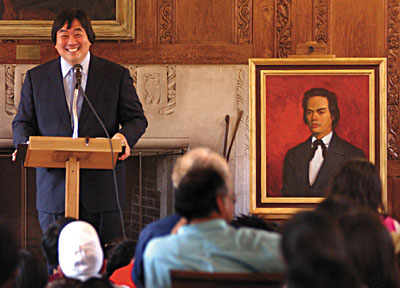

| A portrait of Yung Wing, Yale's first Asian alumnus, was alongside Law School Dean Harold Koh as he recounted Wing's life story in a recent talk. |

When Chinese native Yung Wing came to campus in the mid-1800s, there were "precious few people of color, no women and virtually no non-Christians," said Law School Dean Harold Hongju Koh in a recent talk.

"As the only yellow in a white world, Yung Wing was at best a curiosity and at worst a freak," asserted Koh. Yet, Yung Wing's story is ultimately one of "accomplishment," he noted. "In a very real sense, he is the spiritual ancestor of every one of us of Asian heritage who studies or works here at Yale today."

The dean's talk was the first in a year-long series of campus events honoring Yung Wing, who became Yale's first Asian alumnus -- and likely the first Asian to earn a bachelor's degree from any Western institution -- when he graduated from the University 150 years ago. The event brought an overflow crowd to the Graduate School on Sept. 27.

Koh began his talk, titled "Yellow in a White World," by recounting Yung Wing's tale: His early education in China by Christian missionaries, including Yale alumnus the Reverend Samuel Robbins Brown; his journey to the United States and his matriculation at Yale, where he "made a sensation for bearing off repeated prizes for English composition" and first conceived the idea of bringing other Chinese youths to the West for education; and his return to his homeland, where he found that he had been

Yung Wing spent most of his life traveling between the East and the West, never really at home in either place, Koh said, noting that "In America, he felt Asian; in Asia, he felt American." When Yung Wing volunteered to fight for the Union army during the Civil War, for example, he was turned down because "he was not really an American," added the dean.

In China, Yung Wing worked to promote the nation's modernization. In the 1870s, his earlier vision was realized when he convinced the Chinese government to send 120 youths to schools in the West, including Yale, "to promote mutual cultural understanding and to extend the reach of the Chinese empire," Koh said. Although the Chinese Educational Mission was abruptly ended after only nine years, those students went on to become China's "first generation of 20th-century railroad builders, engineers, medical doctors, naval admirals and diplomats," Koh noted.

While leading the Chinese Educational Mission, Yung Wing received an honorary degree from the Law School, "which makes him, I'm almost sure, the first Asian ever to receive a degree from the school of which I am now dean," said Koh. Yung Wing married an American woman, who returned with him to China, where he later served in the provincial government and became a diplomat. The couple's two sons both went to Yale, and Yung Wing is buried alongside his wife in Hartford, Connecticut.

"Perhaps in Yung Wing's story, you've heard echoes of your own life," said Koh to the audience, noting that it was certainly true in his own case.

Koh's own parents came to the United States from Korea about 100 years after Yung Wing. His mother was a freshman studying sociology, and his father was one of the first Koreans, "if not the first," to earn a law degree in America, he told the audience.

"Like Yung Wing, my parents came away from their educational experience determined to promote mutual understanding between the United States and their home country, Korea," he explained. His parents founded the East Rock Institute in New Haven to carry on that cause, and his father served as the Korean ambassador to the United Nations and as a minister at Korea's embassy in Washington, D.C. He was also an educator who taught courses on East Asian law and society at institutions throughout Connecticut, including Yale.

Like Yung Wing, Koh's parents helped hundreds of Korean students come to the United States to study, and they frequently invited those students to dinner in their home.

"So many Korean students came to my house that we had a regular chair that was just left available for whoever was coming to dinner that night," Koh said. "When I was [U.S.] assistant secretary of state, I went back to Korea a few years ago. Hundreds of well-meaning Korean government officials came to me and said, 'I ate dinner at your house.'"

There are many truths that can be gleaned from Yung Wing's story, Koh told the audience. Chief among these, he said, is "a lesson about making our own choices, no matter how difficult they might be."

Koh remembers watching "Perry Mason" as a youngster and asking his father if he should become a lawyer. "My father turned to me and said just two words: 'Study physics,'" he recalled.

The dean told the audience he later realized that underlying his father's urging were certain "assumptions about choices" -- notably, that law is for "insiders" and "we are outsiders in this country," whereas physics is a profession that is "truly open to Asians"; and that law is not an exact science, and "we will suffer from its inexactness," while in exact sciences such as physics, "they cannot discriminate against you," explained Koh.

Although Koh did study physics for nearly 10 years, he decided that law was his true vocation. He wasn't daunted by the "old boy network" and, he said, "It didn't matter that law was not an exact science because, as it turned out, I wasn't very good at exact sciences."

Over a century after Yung Wing, Koh still found few Asian faces among his classmates at Harvard, and the only Asian names he encountered in the Supreme Court cases he studied "were always litigants and never lawyers," recalled the dean, adding that the history of Asian Americans is "not a story of victors of justice, but victims of injustice."

Today, the world of academia is very different, he said. "If you look over classrooms at Yale and the Yale Law School, you see a huge increase in the number of yellow faces." The population of Yale College is now 13% to 15% Asian American, and about one-tenth of the international students at Yale are of Asian ancestry. "More than that, the world is not nearly as white as it was. The United States has become a strikingly diverse country, and the number of Asians is growing," he said. "What we have now is a different kind of Asian experience."

Another lesson inherent in Yung Wing's story is that of one's obligation to others, asserted Koh, urging audience members "to be a bridge between two cultures, to be a ladder for those who come behind, to be a beacon to those who look for us for leadership because of our unique educational advantages, and most of all, to represent not just those people who are like us in appearance, but those who stand for the same principles."

Yung Wing's story also reveals "how one person, even a solitary yellow in a white world, can make a difference," said Koh, pointing to the Yale alumnus' legacy -- the Yale Library's world-renowned East Asian Collection, which was founded with a gift of books from Yung Wing; the Yale-China Association, which promotes East-West cultural understanding and educational exchange; the Yale China Law Center, which is working to modernize that nation's legal system; and the delegation of Chinese university administrators who came to Yale this summer to learn about the operations of U.S. universities, which Koh described as a "modern-day Chinese mission to New Haven."

All this shows that "people can change institutions, institutions can build legacies and legacies can make history," asserted Koh.

"And so, my friends, that's Yung Wing's story. It is a story of what it means to be yellow in a white world. It's a story of choices; it's a story of hope; it's a story of obligation; it's a story of accomplishment," said Koh. "But most of all, I think, it's a story of justice -- the justice that Asian Americans seek, and the justice that Asian Americans can create with the help of their friends and their colleagues."

Noting that Martin Luther King Jr. once said "The moral arch of the universe is long, but it bends toward justice," Koh concluded: "If Yung Wing were here, I think he would have to agree."

-- By LuAnn Bishop

T H I S

Story of a 'solitary yellow in a white

world' is tale of hope, says Koh

so changed by his experience in America that his countrymen could no longer understand his Chinese and he could barely understand theirs.

Streaming video of Dean Koh's talk is available here.

W E E K ' S

W E E K ' S S T O R I E S

S T O R I E S![]()

Andrew Hamilton named Yale Provost

Andrew Hamilton named Yale Provost

![]()

![]()

Yale rated tops in Fulbright grant winners

Yale rated tops in Fulbright grant winners

![]()

![]()

Program marks 35 years of helping youngsters succeed in school

Program marks 35 years of helping youngsters succeed in school![]()

![]()

Interest in community building, world of theater . . .

Interest in community building, world of theater . . .

![]()

![]()

Story of a 'solitary yellow in a white world' is tale of hope, says Koh

Story of a 'solitary yellow in a white world' is tale of hope, says Koh

![]()

![]()

Yale Employee Day at the Bowl will feature free giveaways

Yale Employee Day at the Bowl will feature free giveaways

![]()

![]()

This year's Divinity School Convocation features concert . . .

This year's Divinity School Convocation features concert . . .

![]()

![]()

Event explores the future of Judaism

Event explores the future of Judaism

![]()

![]()

Design icon William Morris is focus of new exhibit

Design icon William Morris is focus of new exhibit

![]()

![]()

Event celebrates law professor's scholarly work

Event celebrates law professor's scholarly work

![]()

![]()

Physical basis of hereditary pain syndrome identified

Physical basis of hereditary pain syndrome identified

![]()

![]()

Study reveals crucial role of lipid in synaptic transmission

Study reveals crucial role of lipid in synaptic transmission

![]()

![]()

Model shows most recent common ancestor of today's humans . . .

Model shows most recent common ancestor of today's humans . . .

![]()

![]()

Researchers discover VEGF molecule plays key role in asthma

Researchers discover VEGF molecule plays key role in asthma

![]()

![]()

Dr. Martin Gordon wins medical school honor

Dr. Martin Gordon wins medical school honor

![]()

![]()

Engineer T.P. Ma recognized for his scientific accomplishments

Engineer T.P. Ma recognized for his scientific accomplishments

![]()

![]()

Martin Saunders is cited by the American Chemical Society

Martin Saunders is cited by the American Chemical Society

![]()

![]()

Sherwin receives award for efforts in diabetes treatment, research

Sherwin receives award for efforts in diabetes treatment, research

![]()

![]()

Memorial service for Dr. Frederick Redlich

Memorial service for Dr. Frederick Redlich

![]()

![]()

Campus Notes

Campus Notes

![]()

Bulletin Home |

| Visiting on Campus

Visiting on Campus |

| Calendar of Events

Calendar of Events |

| In the News

In the News![]()

Bulletin Board |

| Classified Ads

Classified Ads |

| Search Archives

Search Archives |

| Deadlines

Deadlines![]()

Bulletin Staff |

| Public Affairs

Public Affairs |

| News Releases

News Releases |

| E-Mail Us

E-Mail Us |

| Yale Home

Yale Home