| President Richard C. Levin greets a new freshman and her mother. |

The following is the text of the Freshman Address delivered by President Richard C. Levin on Aug. 27 in Woolsey Hall.

Good morning. I am delighted to join Dean Salovey in welcoming the Yale College Class of 2009. And I want to extend a warm welcome also to all the parents, relatives and friends who are here this morning. To you parents, thanks for entrusting your children to us. We share your high opinion of them, and we are confident that they will thrive here.

Earlier this month, as I was thinking about what I might say to you on this occasion, my wife Jane and I visited the recently renovated Museum of Modern Art in New York. There it was my good fortune to see a brilliantly conceived special exhibition of the works of two French impressionist painters, Camille Pissarro and Paul Cézanne. The exhibition covers the period from 1865 to 1885, when the two artists were in very frequent contact, often spending weeks together painting side-by-side.1

Pissarro was 35 when their close friendship developed, and Cézanne was 26. So they were not exactly your age. But I was struck by the many parallels between their experience and the experience that you are about to have here at Yale. And so by telling you a little about them, I hope to give you a partial introduction to your next four years.

Pissarro and Cézanne met in Paris, at the time the unquestioned capital of the world of art, and a great center of intellectual life. Unlike many artists, they had no connection to the upper strata of French society. Their origins were culturally diverse and middle class. Pissarro had been born in the Carribean, on the island of St. Thomas, where his father had come from France to take over a troubled family business. Cézanne was a native of Provence, in the south of France. His father sold hats, and later founded a small bank. Both painters had mothers described as "Creole," a term which at the time referred to individuals whose ancestors included either natives or long-time European settlers of the Americas.

You, too, come to a great center of learning, to one of the world's great universities, where you will have daily contact with a faculty whose research, writing, and teaching is constantly reshaping the way we think about literature, the arts, history, nature, the economy and society. Some of you come from great wealth, some from great hardship, but most of you, like Cézanne and Pissarro, are somewhere in the middle and come from afar. You represent 50 states and 42 foreign nations. And you have very diverse interests: academic, artistic, and athletic, ranging from debate to drama, from science to surfing to Irish stepdancing.

Cézanne and Pissarro became acquainted at a time of great unrest in the world of art. The recognized masters of the day were superb technicians who created rich, lustrous paintings, but their subject matter was highly formalized and allegorical -- full of allusion to classical texts, ancient history, and mythology. These "academicians" controlled access to national recognition for younger artists, judging whose work would be shown at the great annual national exhibition -- the Salon.

By the time Cézanne first arrived in Paris, Pissarro had already established himself as one of the leaders of a group of young artists in rebellion against the aesthetics of the Academy. Although they respected the technical proficiency of the academicians, the younger artists, like the romantic poets who preceded them by a half century, aimed at a radical simplicity. Instead of elaborate allegorical compositions, they preferred to respond to nature directly -- expressing their individuality through painting from still life or the simplest outdoor scenes. Their intention, articulated in some of the earliest correspondence exchanged by Pissarro and Cézanne, was to give a truthful representation of one's own "sensations," one's individual experience of the physical world.

The two painters quickly developed a mutual admiration. As outsiders, they shared a common bond. Both were deeply passionate about art and committed to a revolutionary aesthetic. Both worked fanatically hard. Beyond this, Cézanne was impressed by the older artist's ability to conceptualize their work and to serve as a leader and model for the young artists who would eventually constitute the impressionist school. Pissarro admired Cézanne's audacity, his raw talent, and his extraordinary sense of color. He did everything he could to advance the younger painter's career. Indeed, throughout their lives, even after they grew distant after 1885, they took pleasure in each other's excellence.

You, too, will develop admiration for one another and come to take pleasure in each other's excellence. In these early days at Yale, as you discover in conversation after conversation the astonishing accomplishments of your classmates, you may be wondering; how can I possibly excel here? But, believe me, one of the glories of this place is that there is room for everyone to excel. You will be pleased to learn that you don't need to compete with the person sitting to your right or to your left. You will find yourself rejoicing in the success of your classmates, just as they rejoice in yours. There is so much room for individual achievement here -- in many different fields of study and many different activities -- music, theater, journalism, community service, athletics, and more.

Cézanne and Pissarro repeatedly found inspiration in each other's work. They experimented with a wide variety of techniques -- borrowing them from each other, sometimes rejecting them, sometimes returning to them years later. During one period in the late 1870s, Pissarro experimented with Cézanne's much more vivid palette of greens and reds only to return to his more subtle greys. A few years later, Cézanne began to emulate Pissarro's work of the late 1860s, which resembled his own mature style more than Pissarro's work of the impressionist period.

Like Cézanne and Pissarro, you, too, will be drawn to each other, attracted sometimes by a common interest and sometimes by interesting differences. You will learn from one another. Sometimes, you'll seek to be like one another. You'll experiment, separately and together, trying out new ideas, exploring new subjects, pursuing new activities. And I encourage you to experiment. Yale will not serve you best if you do nothing but deepen the interests you already have and make friends only with those most like you. You'll learn the most by trying out new ideas and new activities, and by getting to know people whose experiences and values are least like your own.

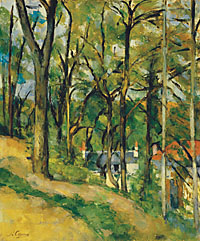

As much as Cézanne and Pissarro learned from one another, each developed a distinctive individuality. Let me illustrate by reference to the two pairs of paintings reproduced on your handout. Side 1 depicts two representations of the same scene in Louveciennes. The first was painted by Pissarro in 1871, and borrowed a year later by Cézanne so that he might study it and make a "copy." (These paintings can be viewed online at www.moma.org/exhibitions/2005/cezanne_pissarro.html.) The scene is recognizably the same, and, at this early stage of their relationship, the paintings are more alike than different. Yet there is no doubt that our two artists are experiencing something different in the same scene. For Pissarro, the world is full of browns and greys, where Cézanne sees green, red, orange, and yellow. Look at the Pissarro's finely painted details in the leaves of the trees and the pattern of stones in the wall. Cézanne sees bolder patches of color where Pissarro sees delicate detail. The overall impression is that Pissarro's image of the scene is finer, Cézanne's is bolder.

President Levin noted that this second pairing of paintings by Camille Pissaro (left) and Paul Cézanne -- both titled "Orchard Coté Saint-Denis at Pontoise" and both from the exhibit "Pioneering Modern Painting: Cézanne and Pissarro 1865-1885" on view at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City through Sept. 11 -- were created as the artists stood side-by-side, and yet reveal the differences in their styles. (The pair of paintings can be viewed online at www.moma.org/exhibitions/2005/cezanne_pissarro.html.)

Cézanne's trees, by contrast, are thicker, heavier. Detail of branch and leaf structure has given way to abstract patches of paint oriented largely on the diagonal, giving this painting a geometry and a sense of motion that is radically different from Pissarro's. Cézanne's colors remain richer and more vivid; he is once again bolder and more dramatic than Pissarro. And, in contrast to the richly textured surface built up by the elder artist, Cézanne applies his patches of color with a palette knife, creating a much flatter, more uniform surface -- a technique that both artists had explored together but abandoned years earlier.

I think you can see what I am trying to say. Like Cézanne and Pissarro you've come as strangers to a new place. Like them, you will become passionate about what you do here. You will work hard. I hope that, like Cézanne and Pissarro, you will aspire to change the world.

You will form close friendships here. You will find classmates and teachers you admire and wish to emulate. You will learn from them and they will learn from you. You will experiment, exploring new subjects and new activities. And all the while, in the classroom and outside, you will expand your capacity to think independently and creatively.

In the end, you will become the person you choose to become. Like Cézanne and Pissarro, you will each develop your own distinctive character. To help you do this, Yale offers you resources that are beyond imagining -- teachers, classmates, libraries, and museums with few equals in all the world. The University Art Gallery has excellent examples of the work of Cézanne and Pissarro. At the reception following this ceremony, you will find a wonderful Pissarro portrait hanging over the fireplace to your left as you enter the President's House. Go to it! Yale is yours. Make the most of it.

1. The historical material that follows is drawn from the excellent exhibition catalogue written by Joachim Pissarro, the artist's great-grandson: "Pioneering Modern Painting: Cezanne and Pissarro 1865-1885," New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2005.

T H I S

Friendship and Individuality

Now consider the second pair of paintings. These were created as the artists stood at their easels side-by-side, six years later. The differences between these two paintings are no longer so subtle. Pissarro's trees are slender, vertical, elegant. The leaf structure is less precise than in his earlier work, but still gives the impression of lightness and laciness. His palette is more varied, but still dominated by subtle variations of grey. What can't be seen in the reproduction is that the surface is built up by thousands of tiny brush strokes, to create a dense, lustrous image.

W E E K ' S

W E E K ' S S T O R I E S

S T O R I E S![]()

University greets its newest freshmen

University greets its newest freshmen![]()

![]()

Freshman Address by President Richard C. Levin

Freshman Address by President Richard C. Levin![]()

![]()

Freshman Address by Yale College Dean Peter Salovey

Freshman Address by Yale College Dean Peter Salovey![]()

![]()

President of China to speak at Yale Sept. 8

President of China to speak at Yale Sept. 8![]()

![]()

New dean to promote 'values' seminars at SOM

New dean to promote 'values' seminars at SOM![]()

![]()

Scientists correct key error in measurement of global warming

Scientists correct key error in measurement of global warming![]()

![]()

ENDOWED PROFESSORSHIPS

ENDOWED PROFESSORSHIPS

Joel Podolny named Beinecke Professor of Management

Joel Podolny named Beinecke Professor of Management![]()

Emilie Townes is appointed to Andrew Mellon Professorship

Emilie Townes is appointed to Andrew Mellon Professorship ![]()

Thomas Troeger is designated as the Cox Lantz Professor

Thomas Troeger is designated as the Cox Lantz Professor![]()

![]()

Grant to support research into reducing pain of pediatric surgery

Grant to support research into reducing pain of pediatric surgery![]()

![]()

Invitation to Yale community: Meet the new World Fellows

Invitation to Yale community: Meet the new World Fellows![]()

![]()

University celebrates Sterling Library's 75th anniversary

University celebrates Sterling Library's 75th anniversary![]()

![]()

Conference will focus on role of religion in public life

Conference will focus on role of religion in public life![]()

![]()

Yale engages in special community projects during 'Days of Caring'

Yale engages in special community projects during 'Days of Caring'![]()

![]()

Yale hockey star Helen Resor is picked for U.S. Women's National Team

Yale hockey star Helen Resor is picked for U.S. Women's National Team![]()

![]()

Descendents of John Davenport to converge on campus

Descendents of John Davenport to converge on campus![]()

![]()

The Cinema at Whitney, a new film society, begins weekly screenings

The Cinema at Whitney, a new film society, begins weekly screenings![]()

![]()

Heart-attack patients seeking after-hours care . . .

Heart-attack patients seeking after-hours care . . .![]()

![]()

While You Were Away: The Summer's Top Stories Revisited

While You Were Away: The Summer's Top Stories Revisited![]()

![]()

Cell biologist named Bayer Fellow

Cell biologist named Bayer Fellow![]()

![]()

IN MEMORIAM

IN MEMORIAM

Abraham Goldstein, former dean and criminal law scholar

Abraham Goldstein, former dean and criminal law scholar![]()

John-Michael Montias, economist and expert on Vermeer

John-Michael Montias, economist and expert on Vermeer![]()

Drama school hosts a memorial tribute to . . . Benjamin Mordecai

Drama school hosts a memorial tribute to . . . Benjamin Mordecai![]()

![]()

Campus Notes

Campus Notes![]()

Bulletin Home |

| Visiting on Campus

Visiting on Campus |

| Calendar of Events

Calendar of Events |

| In the News

In the News![]()

Bulletin Board |

| Classified Ads

Classified Ads |

| Search Archives

Search Archives |

| Deadlines

Deadlines![]()

Bulletin Staff |

| Public Affairs

Public Affairs |

| News Releases

News Releases |

| E-Mail Us

E-Mail Us |

| Yale Home

Yale Home