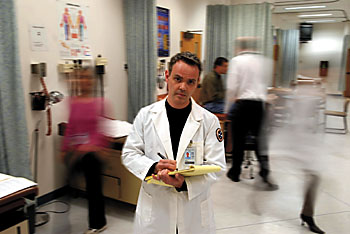

| Once a professor of philosophy, Mark Lazenby is bringing his interest in ethical issues to the clinic as an advance practice nursing student at Yale. |

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2007 issue of Yale Nursing Matters, a publication of the Yale School of Nursing and the Yale Nursing Alumnae/i Association.

Mark Lazenby walks into her room and, recognizing the language she is speaking, he begins to recite the opening words of the Qur'an: Bismillah al-Rahman al-Raheem, an Arabic phrase any Pakistani would recognize. Suddenly the woman becomes quite calm.

Lazenby's gesture seems like the kind of expert practice that might develop over years of meeting patient needs. In fact, he is in his first semester at the Yale School of Nursing (YSN) in the Graduate Entry Prespecialty in Nursing. A few months ago, he was a professor of philosophy.

As a philosopher, Lazenby has mused a good bit about the nature of compassion. Those musings took on an urgency when he watched his father die of a neurodegenerative disease and was appalled by the lack of palliative care available. Lazenby came to believe that when compassion is entirely an emotional exercise it becomes easy to bestow it only on "those we know and love." So he began to think of compassion as an imaginative exercise instead.

While admitting that it is impossible to fully know a patient's suffering, he says imagining that suffering is a constructive step toward better care. When encountering the Pakistani woman who felt such distress, he imagined himself in a hospital in need of care in a strange place where he doesn't speak the language, perhaps Karachi. What would comfort him? Words from a book that had a deep meaning for him.

His attachment to books is profound. Lazenby grew up in a family that practiced a conservative form of Christianity whose adherents see themselves as separate from mainstream society and do not believe in formal education. His parents sent him to public school only to stay on the right side of the law and were upset by much of what was taught there, particularly evolution. But, encouraged by a high school counselor, Lazenby decided to go on to college and eventually earned his doctorate. "It was rebellious, lonely. Blazing my own path," he recalls.

He had success, however, on that lonely path. He authored a book, "The Early Wittgenstein on Religion" which was published in 2006, and was granted tenure at a small liberal arts college just as he received his acceptance to YSN. "It's quite a shift," he says, about going from professor to student. "Novice doesn't even describe it."

But the decision was clear: Lazenby was going to come to Yale to become an advanced practice nurse.

"I'm not sure how much of a religious person I am. I'm not going to invoke God," he says. "But it's a calling. There is some sort of unction that I just can't let go of this."

That calling is drawing him to oncology nursing, where his interests are palliative care and ethical end-of-life issues. By and large, according to Lazenby, theologians and philosophers do not approach palliation and end-of-life with an understanding of the clinical issues involved. Philosophers interested in pain, for example, are interested in it as an example in the great many and difficult issues involved in the philosophy of mind, and theologians are interested in it to settle the issue of the nature of God's being. "On the other side," he says, "the medical perspective I've read does not always have a good grasp of philosophical and religious issues involved."

He explains his aim: "I want to bring to my philosophical work on pain not only an awareness of the technical issues in the philosophy of mind, but also everyday clinical realities. And I want to bring to my clinical work the complexity of philosophical and theological argument."

He adds, "I think many philosophers and theologians don't understand fully the clinical demands of everyday practice."

Lazenby may not spend his whole career in clinical practice, but he believes it is essential that he work for a time as an advanced practice nurse to gain perspective on the ethical issues that fascinate him.

Twice, Lazenby has watched parents die and wished that an advance practice registered nurse (APRN) had been part of the care team. When his father had progressive supranuclear palsy, the man lived in a community with no hospice care and so could not die at home. Lazenby was struck by how badly the high-tech health care system was designed to offer his father symptom relief and offer support to the family.

During the summer between his acceptance at YSN and the start of his first semester of classes here, his mother was ill with colorectal cancer. When she contracted sepsis and disseminated intravascular coagulation, a clotting disorder, Lazenby had difficulty getting information on these conditions from any of the hospital staff. He placed a long-distance call to YSN associate professor Tish Knobf, who told him more in a few minutes than he'd been able to glean from any conversations with his mother's actual caregivers. Knobf advised him to find an APRN at the hospital and get that person involved in his mother's care. Unfortunately, there were no APRNs at the facility.

The experience of his mother's death reinforced the conviction that had sprung from his father's: The health care system must become "one that really is shaped by a model of care and not a model of systems and the science of medicine," he says.

Lazenby's seven-year-old son does not understand his father's new undertaking but simply knows that dad no longer has the summers off and spends more hours studying than playing. "You should be a professor, again," the boy insists. But it's an argument the child will lose -- at least for the foreseeable future -- as Lazenby has a zeal that he finds himself expressing in the religious terms of his youth.

"If I can preach compassion as an imaginative exercise, then I will have done what I wanted to do," he says.

T H I S

Bringing a philosophical

perspective to palliative care

A Pakistani woman is admitted to a New Haven hospital for cancer care. She is frightened and appears confused, which may be why she lapses into Urdu periodically as the medical team asks her questions. Her voice rises along with her anxiety.

W E E K ' S

W E E K ' S S T O R I E S

S T O R I E S![]()

Co-evolution of genitalia in waterfowl reveals 'war between the sexes'

Co-evolution of genitalia in waterfowl reveals 'war between the sexes'![]()

![]()

Study of Galápagos tortoises' DNA may locate mate for 'Lonesome George'

Study of Galápagos tortoises' DNA may locate mate for 'Lonesome George'![]()

![]()

Eighteen new Yale World Fellows named

Eighteen new Yale World Fellows named![]()

![]()

Health clinic staff among the winners of Elm-Ivy Awards

Health clinic staff among the winners of Elm-Ivy Awards![]()

![]()

Bringing a philosophical perspective to palliative care

Bringing a philosophical perspective to palliative care![]()

![]()

University breaks ground for its 'most green building'

University breaks ground for its 'most green building'![]()

![]()

Child Study Center recognized for leadership in autism research

Child Study Center recognized for leadership in autism research![]()

![]()

Yale senior Rebekah Emanuel wins Simon Fellowship for Noble Purpose

Yale senior Rebekah Emanuel wins Simon Fellowship for Noble Purpose![]()

![]()

Using molecular 'nanosyringe,' researchers demonstrate . . .

Using molecular 'nanosyringe,' researchers demonstrate . . .![]()

![]()

Irish writer's play about Siamese twins wins Yale Drama Series award

Irish writer's play about Siamese twins wins Yale Drama Series award![]()

![]()

When it comes to grades, giving is no easier than receiving, says panel

When it comes to grades, giving is no easier than receiving, says panel![]()

![]()

Talents of drama students showcased in Carlotta Festival

Talents of drama students showcased in Carlotta Festival![]()

![]()

Biophysicist Steitz honored for ribosome research with Gairdner Award

Biophysicist Steitz honored for ribosome research with Gairdner Award![]()

![]()

CCL renovations on schedule; lawn to be used for Commencement

CCL renovations on schedule; lawn to be used for Commencement![]()

![]()

Project aims to improve financial services for those living in poverty

Project aims to improve financial services for those living in poverty![]()

![]()

Pastoral leadership skills are focus of Center for Faith and Culture event

Pastoral leadership skills are focus of Center for Faith and Culture event![]()

![]()

MacMillan Center honors the work of three Yale faculty members

MacMillan Center honors the work of three Yale faculty members![]()

![]()

Yale has highest number of sports teams honored . . .

Yale has highest number of sports teams honored . . .![]()

![]()

WORKSPACE ENHANCEMENTS AT THE SCHOOL OF MEDICINE

WORKSPACE ENHANCEMENTS AT THE SCHOOL OF MEDICINE

Adding some sunshine to a windowless office

Adding some sunshine to a windowless office![]()

Creating a tranquil space for nursing mothers

Creating a tranquil space for nursing mothers![]()

Decking the hallways with quilted artworks

Decking the hallways with quilted artworks![]()

![]()

Campus Notes

Campus Notes![]()

Bulletin Home |

| Visiting on Campus

Visiting on Campus |

| Calendar of Events

Calendar of Events |

| In the News

In the News![]()

Bulletin Board |

| Classified Ads

Classified Ads |

| Search Archives

Search Archives |

| Deadlines

Deadlines![]()

Bulletin Staff |

| Public Affairs

Public Affairs |

| News Releases

News Releases |

| E-Mail Us

E-Mail Us |

| Yale Home

Yale Home