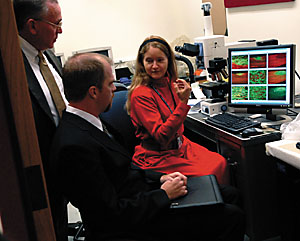

| Yale researcher Karen Lankford (right ) shows ensheathing cells in a microscope to Thomas Stripling (left) and Louis Irvin of the Paralyzed Veterans Association |

One day in 1992 Louis Irvin was in a remote location in the South Pacific working on weapons control and missile guidance systems with the U.S. Navy when he tried to open a desk drawer that was jammed shut. And then his life changed forever.

He thought he had just pulled a muscle in his neck, but three days later he was lying in his bunk with very little sensation from the neck down. Irvin had ruptured a cervical disc, one of the "cushions" between the spinal vertebrae. He was 22 years old.

"The disc had been injured, creating pressure inside the membrane that surrounds the disc," Irvin explained. "The membrane cracked, and grey and white matter from the disc pushed out into the spinal column and pinched the cord, causing the injury."

Technically, Irvin, executive director of the Paralyzed Veterans of America (PVA), is considered an incomplete quadraplegic because he can move his left hand and has other muscle groups that work sporadically. But he spends much of his time in a wheelchair, which is where he was when he visited the Neuroscience and Regeneration Research Center at the School of Medicine recently with three other veterans in wheelchairs.

The PVA been supporting spinal cord research at Yale since 1986, and this year was no exception. They contributed $250,000 to the research center, which is based at the Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System in West Haven.

"Supporting this research can benefit everyone because everyone has a spinal cord and anybody can get injured at any given time, like I did," said Irvin, who married a year ago and lives in Arlington, Virginia. "Because of the pace of activity in spinal cord research, and the pace of technology itself, I think a cure will be found in my lifetime."

Dr. Stephen Waxman, chair of neurology and director of the leader on research in spinal cord injury and related disorders since it was established. "Our research center here at Yale was born with the support of PVA, and we are very proud of this partnership," he says.

Provost Andrew Hamilton, an organic chemist with his own active lab, said the center is at the forefront of research since some of the discoveries are already being explored in human subjects. "Your role is not just financial, although that is very important," he told the veterans. "You remind everyone here why they are doing this research."

Irvin and the other veterans watched intently as they were shown slides demonstrating progress in several different areas. They also had the opportunity to meet with staff, students and postdoctoral fellows from around the world.

Dr. Jeffery Kocsis, professor of neurology and associate director of the research center, is studying olfactory ensheathing cells -- that is, cells that insulate olfactory nerves, such as messengers of smell from the nose to the brain. He wants to learn to do for the spinal cord what olfactory cells do for olfactory nerves. Olfactory cells do not have "stop-sign molecules" that slow or stop regeneration in the adult spinal cord, he explained -- these versatile cells also produce new myelin and proteins that will protect the damaged nerve.

The research center also has made great strides in understanding neuropathic pain, or pain that results from injury to the nervous system. Most recently the Waxman research team uncovered the cause of the rare inherited pain syndrome erythromelalgia, which is triggered by warm temperatures and exercise and causes an intense burning pain, often in the hands and feet. Patients with this problem do not respond to pain medication.

Waxman's team discovered people with erythromelalgia have mutated sodium channels, which are cell membrane structures. In this case, the sodium channels cause nerves to become hypersensitive, fire repeatedly and cause pain. A similar mechanism is believed to cause other forms of neuropathic pain. The Department of Veterans Affairs, which also sponsors this research, has a special interest in pain in limbs that either have been lost or are no longer functioning.

Irvin has never suffered from neuropathic pain, but his story illustrates the devastating effects of spinal trauma. When his neck still hurt the day after he tried to open the desk drawer, he went to see a corpsman, who prescribed a muscle relaxant. Then Irvin stood watch, but couldn't find a comfortable position. He went back to bed. By then the pain was so severe he could only lie on the hard floor. The morning of the third day, the corpsman gave him a small dose of valium, and 20 minutes later Irvin lost sensation in virtually every area of his body below his neck.

Because he was in a very remote location, that he could not disclose, even now, it took three more days to fly him off the ship to Guam, where he was examined, and then transported to Hawaii for surgery. By then the effects of the trauma were irreversible.

Members of the PVA and others interested in the research at Yale were enthusiastic about the progress being made. Waxman, who said he had not been able to use the word "cure" until a few years ago, asserted that he now considers a cure to be an "achievable goal." He noted that a cure for spinal cord injury may not require total reconstruction of the injured spinal cord since reconnection of even 10% of the nerve fibers within the motor pathways can allow recovery of the ability to take some steps and, for example, to transfer from a wheelchair to an automobile.

With respect to pain, Waxman said, "the exciting thing is that we are learning more, by the week, about the molecules that cause pain-signaling neurons to scream, when they should be silent, after nerve injury. I'm confident that there will be new, more effective treatments for pain after nervous system injury as a result of this type of work, and it will benefit a lot of people."

Dr. John Booss, professor emeritus of neurology and laboratory medicine at Yale who also served for 12 years as the national program director for the Neurology Service for the Department of Veterans Affairs, said there have been several groundbreaking discoveries in the research center that are important to people with spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, stroke and pain syndromes.

"These include the observation that the insertion of inappropriate ion channels into injured nerve fibers within the spinal cord can lead to the death of the nerve fibers," he said. "This is important because we may be able to target these channels with medications that prevent the death of nerve fibers and thus prevent loss of ability to walk after spinal cord injury. This is also notable because scientists are trying to unravel the cause of nerve fiber degeneration in multiple sclerosis. If that degeneration can be halted, it may be possible to slow or stop the progression of that disease.

"I am also intrigued by work in the research center showing that anti-sense molecules could prevent the formation of certain ion channels," Booss said.

Furthermore, Booss stated he was impressed with the research center's work with olfactory ensheathing cells, both for the capacity to create tunnels in which regenerating nerve fibers might grow toward their targets within the spinal cord, and for their biological effect in neutralizing factors that inhibited such growth.

Thomas Stripling, director of research, education and practice guidelines at PVA, said the organization, through its funding, helped build the structure in which the lab resides with the idea that it would be a flagship venture looking at spinal cord and neuroscience regeneration.

"We have never been disappointed," he said. "The collaborative nature of the project with Yale, the VA, the PVA and the Waxman/Kocsis lab, has always been in evidence. They continue to bring in the best and the brightest. We like to see new people coming into the field with new ideas, new concepts, with strong ambition. We continue to believe that the contributions we witness are well worth the effort."

Irvin said the field of medicine and research has come a long way in improving the quality of life and life expectancy for people with spinal cord injuries and now it is time to pool all resources in the direction of research.

"The question with spinal cord research is whether the solution is already available and is just waiting for someone to see it?" Irvin said. "We need to push harder to find the funding, to find the support, to get to that solution."

-- By Jacqueline Weaver

T H I S

Spinal cord research of special

interest to veterans group W E E K ' S

W E E K ' S S T O R I E S

S T O R I E S![]()

Yale expanding nanoscience, quantum engineering focus

Yale expanding nanoscience, quantum engineering focus![]()

![]()

New York Times editor to teach journalism course

New York Times editor to teach journalism course![]()

![]()

Spinal cord research of special interest to veterans group

Spinal cord research of special interest to veterans group![]()

![]()

Law librarian took the words right out of their mouths

Law librarian took the words right out of their mouths![]()

![]()

Yale research team identifies gene for Crohn's disease

Yale research team identifies gene for Crohn's disease![]()

![]()

ENDOWED PROFESSORSHIPS

ENDOWED PROFESSORSHIPS

Nicholas Barberis is named Schramm Professor of Finance at SOM

Nicholas Barberis is named Schramm Professor of Finance at SOM![]()

Christine Jolls is appointed the Gordon Bradford Tweedy Professor

Christine Jolls is appointed the Gordon Bradford Tweedy Professor![]()

Kenji Yoshino is designated . . . first Guido Calabresi Professor of Law

Kenji Yoshino is designated . . . first Guido Calabresi Professor of Law![]()

![]()

Two investigators win grants for research on women's health issues

Two investigators win grants for research on women's health issues![]()

![]()

Posters showcase work on women and gender

Posters showcase work on women and gender![]()

![]()

Conference exploring the impact of dams . . .

Conference exploring the impact of dams . . .![]()

![]()

Journal's special issue focuses on most environmentally harmful products

Journal's special issue focuses on most environmentally harmful products![]()

![]()

Lectures will examine the reasons for humans' love of music

Lectures will examine the reasons for humans' love of music![]()

![]()

Scientists to discuss their work 'Panning for Gold

Scientists to discuss their work 'Panning for Gold![]()

![]()

Seminar to focus on company's genome sequencing technology

Seminar to focus on company's genome sequencing technology![]()

![]()

Event will showcase cultural dances from around the world

Event will showcase cultural dances from around the world![]()

![]()

Guitar festival will include performances and master classes

Guitar festival will include performances and master classes![]()

![]()

Campus Notes

Campus Notes![]()

Bulletin Home |

| Visiting on Campus

Visiting on Campus |

| Calendar of Events

Calendar of Events |

| In the News

In the News![]()

Bulletin Board |

| Classified Ads

Classified Ads |

| Search Archives

Search Archives |

| Deadlines

Deadlines![]()

Bulletin Staff |

| Public Affairs

Public Affairs |

| News Releases

News Releases |

| E-Mail Us

E-Mail Us |

| Yale Home

Yale Home