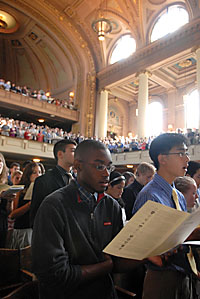

| As sunlight streamed in the windows at Woolsey Hall, members of the Class of 2011 gathered for a formal welcome from President Richard C. Levin and Yale College Dean Peter Salovey. |

President Richard C. Levin formally welcomed the members of the Class of 2011

to campus during the Freshman Assembly on Sept. 1 in Woolsey Hall. The text

of that speech follows. Members of the class of 2011, I am delighted to join Dean Salovey in welcoming

you to Yale College. And I want to extend a warm welcome also to the parents,

relatives, and friends who have accompanied you here. To parents especially,

I want to say thank you for entrusting your very talented and promising children

to us. We are delighted to have them with us, and we pledge to do our best

to provide them with abundant opportunities to learn and thrive in the four

years ahead.

T H I S

The Questions That Matter

Three weeks ago, as you were beginning to prepare yourselves for your journey

to New Haven, I spent a very pleasant weekend reading a new book by one of

our distinguished Sterling Professors, the former Dean of the Yale Law School,

Anthony Kronman, who now teaches humanities courses in Yale College. I had

one of those experiences that I hope you have time and again during your four

years here. I was disappointed to finish reading the book. It was beautifully

written, closely reasoned, and utterly transparent in its exposition and its

logic. I was disappointed because I wanted the pleasure of my reading to go

on and on, through the lovely summer afternoon and well into the evening.

Professor Kronman’s book, “Education’s End,”¹ is at

once an affirmation of the essential value of the humanities in undergraduate

education and a critique of the humanities curriculum as it has evolved over

the past 40 years. Professor Kronman begins with a presumption that a college

education should be about more than acquainting yourself with a body of knowledge

and preparing yourself for a vocation. This presumption is widely shared. Many

who have thought deeply about higher education — including legions of

university presidents starting most eloquently with Yale’s Jeremiah Day

in 1828 — go on to argue that a university education should develop in

you what President Day called the “discipline of the mind” — the

capacity to think clearly and independently, and thus equip you for any and

all of life’s challenges.²

Professor Kronman takes a step beyond this classical formulation of the rationale

for liberal education. He argues that undergraduate education should also encourage

you to wrestle with the deepest questions concerning lived experience: What

constitutes a good life? What kind of life do you want to lead? What values

do you hope to live by? What kind of community or society do you want to live

in? How should you reconcile the claims of family and community with your individual

desires? In short, Professor Kronman asserts that an important component of

your undergraduate experience should be seeking answers to the questions that

matter: questions about what has meaning in life.

Professor Kronman then divides the history of American higher education into

three periods, and he argues that the quest for meaning in life was central

to the university curriculum during the first two, but no longer. In the first

period, running from the founding of Harvard in 1636 to the Civil War, the

curriculum was almost entirely prescribed. At its core were the great literary,

philosophical and historical works of classical Greece and Rome, as well as

classics of the Christian tradition — from the Bible to the churchmen

of late Antiquity and the Middle Ages to Protestant theologians of the Reformation

and beyond. In the minds of those who established Harvard and Yale and the

succession of American colleges that were founded by their graduates, the classics

were the ideal instruments, not only for developing the “discipline of

the mind,” but also for educating gentlemen of discernment and piety.

In this era, Kronman argues, the proposition that education was about how to

live a virtuous life was never in doubt. Through their mastery of the great

texts, the faculty, each of whom typically taught every subject in the curriculum,

were believed to possess authoritative wisdom about how to live, and they believed

it their duty to convey this wisdom to their students.

After the Civil War the landscape of American higher education changed dramatically,

as new institutions like Johns Hopkins, Cornell, and the University of California

took German universities as their model. For the first time, the advancement

of knowledge through research, rather than the intergenerational transmission

of knowledge through teaching, was seen to be the primary mission of higher

education. As faculty began to conceive of themselves as scholars first and

teachers second, specialization ensued. No longer did everyone on the faculty

teach every part of a prescribed curriculum; instead the faculty divided into

departments and concentrated their teaching within their scholarly disciplines.

Dressed for the occasion, new Yale students attended an open house at the President's House, where they were greeted by President Levin and Jane Levin.

Amidst this transformation, explicit discussion of the ,question of how one

should live was more or less abandoned by the natural and social sciences and

left to the humanities. Humanists, like scientists, became specialists in their

scholarship, but they recognized that the domain of their expertise, the great

works of literature, philosophy and history — modern as well as classical — raised,

argued, and re-argued the central questions about life’s meaning. And

they continued to see their role as custodians of a tradition that encouraged

young people to grapple with these questions as a central part of their college

experience. But humanities professors no longer had the moral certainty of

their predecessors. They saw the great works of the past not as guidebooks

to becoming a steadfast and righteous Christian, but rather as part of a “great

conversation” about human values, offering alternative models of how

one should live, rather than prescribing one true path. Engagement with the “great

conversation” remained an important component of college education in

the century between the Civil and Vietnam Wars, a period which Kronman labels

the era of “secular humanism.”

Kronman goes on to argue that since the 1960s, the tradition of secular humanism

has been eroded — he would even say defeated — by two forces. The

first of these forces is a growing professionalization, discouraging humanists

from offering authoritative guidance on the questions of value at the center

of the “great conversation.” The second is politicization, challenging

the view that the voices and topics engaged in the “great conversation” of

western civilization have any special claim to our attention and arguing for

increased focus on the voices and topics, western and non-western, that have

been excluded from the western canon.

Kronman’s argument about the contemporary state of ,the humanities will

be welcomed by some and met with fierce resistance from many others. But the

inevitable controversy about the current state of the humanities should not

obscure for us this most important point: that the question of how you should

live should be at the center of the undergraduate experience, and at the center

of your Yale College experience.

The four years ahead of you offer a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to pursue

your intellectual interests wherever they may lead, and, wherever they may

lead, you will find something to reflect upon that is pertinent to your quest

for meaning in life. It is true that your professors are unlikely to give you

the answers to questions about what you should value and how you should live.

We leave the answers up to you. But I want to make very clear that we encourage

you to ask the questions, and, in seeking the answers, to use the extraordinary

resources of this place — a brilliant and learned faculty, library and

museum resources that are the equal of any campus anywhere, and curious and

diverse classmates who will accompany you in your quest.

Because of their subject matter, the humanities disciplines have a special

role in inspiring you to consider how you should live. But I also want to suggest

to each of you that questions that bear on the shaping of your life will arise

in whatever subjects you choose to study. You will find that virtually every

discipline will provide you with a different perspective on questions of value

and lead you to fresh insights that will illuminate your personal quest.

Your philosophy professors, for example, aren’t likely to teach you the

meaning of life, but they will train you to reason more rigorously and to discern

more readily what constitutes a logically consistent argument and what does

not. And they will lead you through texts that wrestle directly with the deepest

questions of how to live, from Plato and Aristotle to Kant and Nietzsche and

beyond.

Your professors of literature, music, and art history will not tell you how

to live, but they will teach you to read, listen, and see closely, with a keener

appreciation for the artistry that makes literature, music, and visual art

sublime representations of human emotions, values, and ideas. And they will

lead you through great works that present many different models of how, and

how not, to lead a good life.

Neither will your professors of history instruct you on the values that you

should hold most close, but, by giving you an appreciation of the craft of

reconstructing the past, they will lead you to understand how meaning is extracted

from experience, which may help you to gain perspective on your own experience.

And history, too, provides models of how one should, and should not, live.

In your effort to think through how you wish to live and what values matter

most to you, you will find that challenging questions arise not only in the

humanities. Long ago, I taught introductory economics in Yale College. I always

began by telling the students that the course would change their lives. I still

believe this. Why? Because economics will open you to an entirely new and different

way of understanding how the world works. Economics won’t prescribe for

you how society should be organized, or the extent to which individual freedom

should be subordinated to collective ends, or how the fruits of human labor

should be distributed — at home and around the world. But understanding

the logic of markets will give you a new way to think about these questions,

and, because life is lived within society and not in abstraction from it, economics

will help you to think about what constitutes a good life.

Dean Salovey has already given you some insights gleaned from his study as

a professor of psychology. His discipline probes many fundamental questions.

What is the relationship between your brain and your conscious thoughts? To

what extent is your personality — both in its cognitive and emotional

dimensions — shaped by your genetic make-up, your past experiences, and

your own conscious decisions? The answers to these questions have an obvious

bearing on the enterprise of locating meaning in life.

Your biology and chemistry professors will not tell you how to live, but the

discoveries made in these fields over the last century have already extended

human life by 25 years in the United States. As the secrets of the human genome

are unlocked and the mechanisms of disease uncovered, life expectancy may well

increase by another decade or two. You may want to ponder how a longer life

span might alter your thinking about how to live, how to balance family and

career, and how society should best be organized to realize the full potential

of greater human longevity.

Finally, it is at the core of the physical sciences that one finds some of

the deepest and most fundamental questions relating to the meaning of human

experience. How was the physical universe created? How long will it endure?

And what is the place of humanity in the order of the universe?

For the next four years, each of you has the freedom to shape your life and

prepare for shaping the world around you. You will learn much about yourself

and your capacity to contribute to the world not only from your courses, but

also from the many friends you make and the rich array of extracurricular activities

available to you. Your courses will give you the tools to ask and answer the

questions that matter most, and your friendships and activities will give you

the opportunity to test and refine your values through experience.

Let me warn you that daily life in Yale College is so ,intense that it may

sometimes seem that you have little time to stop and think. But, in truth,

you have four years — free from the pressures of career and family obligations

that you will encounter later — to reflect deeply on the life you wish

to lead and the values you wish to live by. Take the time for this pursuit.

It may prove to be the most important and enduring accomplishment of your Yale

education.

Welcome to Yale College.

1. Anthony T. Kronman, “Education’s End: Why Our Colleges and

Universities Have Given Up on the Meaning of Life,” New Haven and London:

Yale University Press, 2007.

2. “Reports on the Course of Instruction in Yale College.” New

Haven: The Yale Corporation, 1828, p. 7. W E E K ' S

W E E K ' S S T O R I E S

S T O R I E S![]()

Grant to fund study of stress & self-control

Grant to fund study of stress & self-control![]()

![]()

Award-winning researcher named new engineering dean

Award-winning researcher named new engineering dean![]()

![]()

Zipcar service offers environmentally friendly travel option

Zipcar service offers environmentally friendly travel option![]()

![]()

Community invited to meet World Fellows at open house, series

Community invited to meet World Fellows at open house, series![]()

![]()

FRESHMAN ADDRESSES

FRESHMAN ADDRESSES![]()

Britton reappointed to second term as Berkeley Divinity School dean

Britton reappointed to second term as Berkeley Divinity School dean![]()

![]()

Development Office announces new associate vice presidents

Development Office announces new associate vice presidents![]()

![]()

ENDOWED PROFESSORSHIPS

ENDOWED PROFESSORSHIPS

Dr. Richard Belitsky is the Harold W. Jockers Associate Professor

Dr. Richard Belitsky is the Harold W. Jockers Associate Professor![]()

James Duncan is named the Ebenezer K. Hunt Professor

James Duncan is named the Ebenezer K. Hunt Professor![]()

Dr. Erol Fikrig appointed the Waldemar Von Zedtwitz Professor

Dr. Erol Fikrig appointed the Waldemar Von Zedtwitz Professor![]()

Dr. Sally Shaywitz is designated the Audrey Ratner Professor

Dr. Sally Shaywitz is designated the Audrey Ratner Professor![]()

![]()

‘Art for Yale’ celebrates ‘outpouring of gifts’ to gallery

‘Art for Yale’ celebrates ‘outpouring of gifts’ to gallery![]()

![]()

Team seeking key to unlock link between stress and addictive behavior

Team seeking key to unlock link between stress and addictive behavior![]()

![]()

School of Public Health creates new deanship in academic affairs

School of Public Health creates new deanship in academic affairs![]()

![]()

F&ES student working to insure survival of the snow leopard

F&ES student working to insure survival of the snow leopard![]()

![]()

Yale Rep opens its new season with Shakespeare classic

Yale Rep opens its new season with Shakespeare classic![]()

![]()

New York Times columnist to offer ‘Mobile Gadget Show-and-Tell’

New York Times columnist to offer ‘Mobile Gadget Show-and-Tell’![]()

![]()

New works by painter and printmaker Nathan Margalit . . .

New works by painter and printmaker Nathan Margalit . . .![]()

![]()

While You Were Away ...

While You Were Away ...![]()

![]()

Biomass energy is the topic of talk by award-winning engineer

Biomass energy is the topic of talk by award-winning engineer![]()

![]()

In Memoriam: Biochemists Joseph Fruton and Sofia Simmonds

In Memoriam: Biochemists Joseph Fruton and Sofia Simmonds![]()

![]()

Campus Notes

Campus Notes![]()

Bulletin Home |

| Visiting on Campus

Visiting on Campus |

| Calendar of Events

Calendar of Events |

| In the News

In the News![]()

Bulletin Board |

| Classified Ads

Classified Ads |

| Search Archives

Search Archives |

| Deadlines

Deadlines![]()

Bulletin Staff |

| Public Affairs

Public Affairs |

| News Releases

News Releases |

| E-Mail Us

E-Mail Us |

| Yale Home

Yale Home