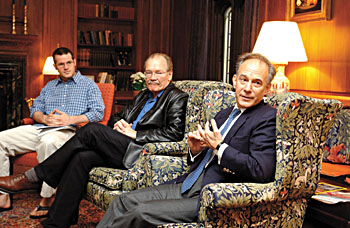

| During his visit to campus as a Poynter Fellow, Washington Post columnist David Ignatius (right) spoke at a tea hosted by Calhoun College master Dr. William Sledge (center). He said that few journalists predicted the danger posed by Osama bin Laden. |

In this "season of second-guessing" regarding the 9/11 attacks and the war on Iraq, members of the media need to ask themselves why they too failed to "connect the dots" and anticipate "what was coming at our country," asserted David Ignatius, associate editor and columnist at The Washington Post, who spoke on campus on April 26 as a Poynter Fellow in Journalism.

"What has largely been missing in this wave of national self-criticism is an honest accounting of the performance of the news media," Ignatius told the audience gathered in Rm. 102 of Linsly-Chittenden Hall. "Journalists are rightly hectoring public officials about how they got it so wrong. But they are not asking the same question of themselves. It's a common failing in our business. We are famously better at dishing it out to others than taking it ourselves."

However, he contended, the media needs to learn from its mistakes "as much as any institution needs to learn from its mistakes."

Pointing to the revelations about what the government knew about al Qaeda's activities prior to the 9/11 attacks, Ignatius said, "We [in the media] didn't have so many dots to connect, but that doesn't mean we had no information." Furthermore, he noted, "the press took the al Qaeda threat less seriously than the CIA, which as we know made many mistakes."

Ignatius told the audience that a search of the Nexis database, which tracks newspaper and magazine coverage nationwide, reveals that there were only 176 stories in The New York Times that mentioned "Osama bin Laden" and "terror" together prior to the terrorist attacks in 2001 -- with other newspapers, including The Washington Post, making that link even less frequently. This is "compared to literally thousands of times since 9/11," noted the journalist.

In fact, "government officials who tried to sound the alert about al Qaeda often encountered a skeptical press," he said.

For example, the press covered the first unsuccessful attempt to destroy the World Trade Center with a car bomb in 1983 as a "botched operation," said Ignatius, rather than conveying "the essential message: that there was a network of terrorists that wanted to kill thousands of American civilians."

After the bombing of the U.S. embassies in East Africa in 1998, the media wrote numerous stories questioning whether President Clinton was pursuing bin Laden too aggressively and others portraying al Qaeda as "slipshod" and full of strife, said Ignatius. In fact, one article compared al Qaeda's manual on terrorism to Mad Magazine's "Spy vs. Spy" cartoons, he noted.

Similarly, the bombing of the U.S.S. Cole in 2000 was a "flashing red light" that the media missed, noted Ignatius, pointing out that The Washington Post did not even make the incident its lead story the next day, focusing instead on an Israeli air strike.

"A few journalists did 'get it' about the danger posed by bin Laden. But I should state clearly that I was not among them," Ignatius confessed to the audience. "I didn't mention Osama bin Laden once in my columns or other journalism before 9/11 despite the fact that I wrote often about the Middle East."

Assessing media coverage of the U.S. intervention in Iraq is "far more complicated," both because there has been much more diversity of reporting and opinion about the war and because it is "hard to evaluate coverage of an event that is still very much in progress," said the journalist.

As someone who had worked in pre-war Iraq, Ignatius said, he personally believed that by "toppling the most tyrannical of the Arab regimes ... that the United States could help open the door to the Arab future. ...

"Believing the war was a good deed, I failed to ask as many questions as I should have -- not so much about how Iraqis would respond to occupation, for I knew that as normal human beings they would hate it, but about whether the United States had a coherent strategy for what to do in post-war Iraq. It's now clear that [government officials] didn't," he said.

This mind-set was also true of many other journalists, he said, noting that a Nexis search of New York Times stories that contained the words "Iraq" and "post-war" before the hostilities turned up only 172 entries -- again, far more than that of other newspapers.

"Lacking hard evidence of our own to rebut or challenge the administration's statements, the press simply reported them, often at face value. We didn't realize at the time how little effective planning they had actually done for the post-war period," said Ignatius.

While some members of the military had "serious questions" about the mission they were being asked to undertake, "these only occasionally made their way into print," said Ignatius, while stories questioning the link between Saddam Hussein and weapons of mass destruction were usually not front-page news but were "buried" inside the paper.

Although there "wasn't much of a pre-war debate" to report, the media's coverage "failed to achieve critical mass, to present anomalous evidence that might have challenged the administration's case in a way that would have forced a broader debate," said Ignatius.

"As I look back on this period, I have come to think that in an odd way we were victims of our own professionalism," he added. "Our notion of professional ethics meant that we couldn't invent a national debate about the war that wasn't really happening."

According to the journalist, the most important lesson members of the media should learn from the problems in their pre-9/11 and pre-war coverage "is, simply, humility.

"The biggest mistake you can ever make as a reporter is to think you understand events when the evidence is limited. The truth is you usually don't know," he said. "That's why you have to stay open-minded and be aggressive, skeptical, curious, persistent -- all of the virtues that journalism schools try to teach -- because you never really know how the story is going to turn out."

Journalists, he added, need to remember that "the events that end up mattering are often the anomalies ... the things that are so unimaginable or sometimes so commonplace that nobody thinks to look for them."

-- By LuAnn Bishop

T H I S

Media failed to 'connect the dots'

before 9/11, journalist says

W E E K ' S

W E E K ' S S T O R I E S

S T O R I E S![]()

Alpern named as new medical school dean

Alpern named as new medical school dean![]()

![]()

Sixteen honored for strengthening town-gown ties

Sixteen honored for strengthening town-gown ties

![]()

![]()

Author Fadiman named first Francis Writer in Residence

Author Fadiman named first Francis Writer in Residence

![]()

![]()

Yale counselor helped ease grief of war-torn families in Kosovo and Iraq

Yale counselor helped ease grief of war-torn families in Kosovo and Iraq

![]()

![]()

Media failed to 'connect the dots' before 9/11, journalist says

Media failed to 'connect the dots' before 9/11, journalist says

![]()

![]()

With a hoisting of tentacles, giant squid returns to Peabody

With a hoisting of tentacles, giant squid returns to Peabody

![]()

![]()

Alumni delegates explore issues . . .

Alumni delegates explore issues . . .

![]()

![]()

Threatened nation-state is topic of two-day YCIAS conference

Threatened nation-state is topic of two-day YCIAS conference

![]()

![]()

Event showcasing medical students' original research . . .

Event showcasing medical students' original research . . .

![]()

![]()

New center offers treatment for primary immunodeficiencies

New center offers treatment for primary immunodeficiencies

![]()

![]()

The letters of literary figures are featured in Beinecke exhibit

The letters of literary figures are featured in Beinecke exhibit

![]()

![]()

In elderly, recovery from injuries often good . . .

In elderly, recovery from injuries often good . . .

![]()

![]()

Study: For-profit hospices offer fewer services than non-profits

Study: For-profit hospices offer fewer services than non-profits

![]()

![]()

Chemotherapy agent called cisplatin effectively transmits . . .

Chemotherapy agent called cisplatin effectively transmits . . .

![]()

![]()

Scientists learn more about bond of water molecules, protons

Scientists learn more about bond of water molecules, protons

![]()

![]()

New fund will support YSN faculty's initiatives to improve health care

New fund will support YSN faculty's initiatives to improve health care

![]()

![]()

Juniors are recognized for scholarship and character

Juniors are recognized for scholarship and character

![]()

![]()

'Modernist Voices' will explore themes in American and British literature

'Modernist Voices' will explore themes in American and British literature

![]()

![]()

Dr. Terri Fried lauded for her work in geriatric patient care and research

Dr. Terri Fried lauded for her work in geriatric patient care and research

![]()

![]()

Event explores new advances in chemical biology

Event explores new advances in chemical biology

![]()

![]()

Yale Books in Brief

Yale Books in Brief

![]()

![]()

Campus Notes

Campus Notes

![]()

Bulletin Home |

| Visiting on Campus

Visiting on Campus |

| Calendar of Events

Calendar of Events |

| In the News

In the News![]()

Bulletin Board |

| Classified Ads

Classified Ads |

| Search Archives

Search Archives |

| Deadlines

Deadlines![]()

Bulletin Staff |

| Public Affairs

Public Affairs |

| News Releases

News Releases |

| E-Mail Us

E-Mail Us |

| Yale Home

Yale Home