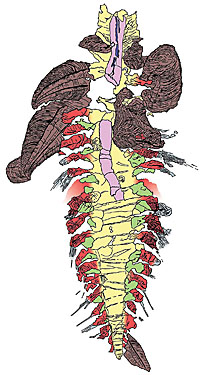

| This newly discovered fossil of an extinct armored machaeridian worm is providing scientists with a more complete picture of the animal's anatomy. |

Discovery of a fossil specimen in southeastern Morocco that preserves evidence

of the animal’s soft tissues has solved a paleontological puzzle about

the origins of an extinct group of bizarre slug-like animals with rows of

mineralized armor plates on their backs, according to a paper in Nature.

— By Janet Rettig Emanuel

T H I S

Fossil solves mystery of

extinct animal's origins

While evolution has produced great diversity in the body designs of animals,

over the course of history several highly distinct groups, such as trilobites

and ammonites, have become extinct. The new fossil is of an unusual creature

known as a machaeridian, an invertebrate (or animal without a backbone) that

existed from 485 to 305 million years ago.

“The new specimen unequivocally identifies machaeridians as annelid worms,

an extremely successful and diverse group of animals that includes familiar living

animals like the sea mouse, the earthworm and the leech,” says ?Jakob Vinther,

a graduate student in the Department of Geology & Geophysics at Yale. The

specimen was found in an area that had earlier been identified as a rich source

of exceptionally preserved fossils including sponges, trilobites, echinoderms

and other less-familiar invertebrates.

First described over 150 years ago, armor plates of these strange animals have

been found in marine fossil deposits worldwide covering the 180 million years

in which they existed, indicating that they were an important component of ancient

seafloor ecosystems. Until now there was little information about their body

design or how they might be related to other ancient — or currently living — animals.

“These animals disintegrated quickly after death, so complete fossils of

their dorsal armor are rare, and their record until now consisted mostly of isolated

armor plates scattered in the sediment,” says Vinther. The dilemma of studying

ancient organisms, he notes, is that the soft body parts, including most internal

organs, are unavailable for study because they usually decompose before they

can become fossilized.

The soft tissues of the machaeridian worm revealed by the fossil: the trunk (yellow), limb (red), bristles (gray), attachment of shell plates (green), gut (purple) and dorsal linear structure (blue).

Previous patchy evidence was insufficient to reveal the relationships of the

machaeridians to other animals, and there was much speculation about their position

in the tree of life. Different authors suggested relationships to groups as varied

as mollusks (clams and snails), barnacles (crustaceans — including shrimps,

crabs and crayfish), echinoderms (starfish and sea urchins) and annelid worms

(aquatic bristle worms and garden earthworms).

The inch-long specimen that was recently discovered shows that, below the dorsal

armor, the machaeridians had an elongate body with paired, soft, limb-like extensions

on each segment, and two bundles of long, stiff bristles on each extension. The

segmented nature of the body, and especially the presence of soft “limbs” carrying

bristles, unequivocally identified the machaeridians as annelid worms, say the

scientists.

According to the authors, although the exact relationship of machaeridians within

the annelid worms is still uncertain, the presence of modified scales suggests

that they may even belong to a group of marine bristle worms that are still in

existence today.

Senior author Derek Briggs, the Frederick William Beinecke Professor of Geology

and Geophysics at Yale, notes: “This exciting discovery has provided important

new insights into annelid evolution, showing that some of these worms, which

first appeared during the Cambrian radiation, evolved a highly distinctive dorsal,

mineralized armor early in their history.

“It also highlights the great importance of the study of exceptional fossil

sites, and of paleobiology in general, for a better understanding of the evolution

of our biosphere,” adds Briggs, who is director of the Yale Institute for

Biospheric Studies and will assume the directorship of the Yale Peabody Museum

of Natural History in July.

The third author of the study is Peter Van Roy at Ghent University (Belgium),

now at University College, Dublin, who first recognized the importance of the

specimen.

W E E K ' S

W E E K ' S S T O R I E S

S T O R I E S![]()

Yale cuts costs for families and students

Yale cuts costs for families and students![]()

![]()

Homebuyer benefit increased

Homebuyer benefit increased![]()

![]()

Fossil solves mystery of extinct animal's origins

Fossil solves mystery of extinct animal's origins![]()

![]()

Team learns Abu Dhabi desert once lush habitat

Team learns Abu Dhabi desert once lush habitat![]()

![]()

Meeting the challenges of nursing care in Nicaragua

Meeting the challenges of nursing care in Nicaragua![]()

![]()

Foundation’s gift to the School of Drama establishes . . .

Foundation’s gift to the School of Drama establishes . . .![]()

ENDOWED PROFESSORSHIPS

Marans has been appointed as Harris Professor

Marans has been appointed as Harris Professor![]()

Medzhitov named first incumbent of Wallace chair

Medzhitov named first incumbent of Wallace chair![]()

State is designated as Cohen Associate Professor

State is designated as Cohen Associate Professor![]()

![]()

Study: Despite efforts, racial disparities in cancer care continue

Study: Despite efforts, racial disparities in cancer care continue![]()

![]()

Law School students argue case before the nation’s highest court

Law School students argue case before the nation’s highest court![]()

![]()

Sharp cited as ‘superb teacher of teachers’

Sharp cited as ‘superb teacher of teachers’![]()

![]()

Events commemorate Martin Luther King Jr. Day

Events commemorate Martin Luther King Jr. Day![]()

![]()

The color printmaking revolution is highlighted in new exhibition

The color printmaking revolution is highlighted in new exhibition![]()

![]()

Symposium to examine the university’s role as architectural patron

Symposium to examine the university’s role as architectural patron![]()

![]()

Forum will explore the use of neuroimaging in study of alcoholism

Forum will explore the use of neuroimaging in study of alcoholism![]()

![]()

Memorial Service for George Hersey

Memorial Service for George Hersey![]()

![]()

Yale Books in Brief

Yale Books in Brief![]()

![]()

Campus Notes

Campus Notes![]()

Bulletin Home |

| Visiting on Campus

Visiting on Campus |

| Calendar of Events

Calendar of Events |

| In the News

In the News![]()

Bulletin Board |

| Classified Ads

Classified Ads |

| Search Archives

Search Archives |

| Deadlines

Deadlines![]()

Bulletin Staff |

| Public Affairs

Public Affairs |

| News Releases

News Releases |

| E-Mail Us

E-Mail Us |

| Yale Home

Yale Home