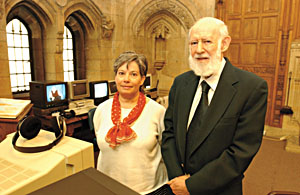

| Joanne Rudof and Professor Geoffrey Hartman oversee an archive that includes more than 4,200 taped testimonies from witnesses to the horrors of the Holocaust. |

For nearly 40 years, whenever Renée Glassner thought or spoke about her childhood experience hiding out from the Nazis, she referred to herself in the third person, as if it had happened to some other young girl.

Only eight years old when the Germans invaded her hometown of Losice in eastern Poland, Glassner spent most of World War II in hiding, living in unremitting terror that she and her family members would be discovered and killed.

Today, Glassner's first-person account of her survival is one of more than 4,200 videotaped accounts by survivors and witnesses in the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies at Yale, which is celebrating its 20th anniversary this year.

Glassner was one of the first survivors to give testimony about her Holocaust experiences for the Yale archive, which is housed in Sterling Memorial Library as part of its Manuscripts and Archives department.

The archive has its roots in a grassroots organization called the Holocaust Survivors Film Project, initiated by local television interviewer and producer Laurel Vlock in association with Dori Laub, an associate professor of clinical psychiatry at Yale and child survivor himself. In 1979 it began videotaping testimony from survivors and witnesses in the New Haven area. When project organizers decided to expand the scope of the project to include testimonies from across the nation, one of their board members -- Geoffrey Hartman, the Sterling Professor Emeritus of English and Comparative Literature -- urged the University to assist the project.

Given its staff's expertise in collections and cataloging, Hartman believed the University Library would be a beneficial resource for the expansion of the project. In 1981, the collection -- which then numbered some 200 testimonies -- came to the Sterling Memorial Library. A grant from the Charles H. Revson Foundation supported the transfer and cataloging of the testimonies, and made it possible for Yale to extend the collection's reach to a national and international level.

The archive became accessible to the public in 1982, and in 1987, the late Alan M. Fortunoff, president of Fortunoff specialty stores, provided endowment funding.

By its 10th anniversary in 1992, the collection of first-hand testimonies -- from survivors, bystanders and rescuers as well as those involved in the Nazi resistance and liberation efforts -- had grown to nearly 2,000. That number has since more than doubled, comprising some 10,000 recorded hours of videotape.

The Fortunoff Archive for Holocaust Testimonies -- which is marking its 20th year with a conference Oct. 6-8 -- is now an international endeavor, having widened its scope to include testimonies from individuals from throughout the world who experienced or witnessed Nazi persecution. With continued support from the Revson Foundation, the archive has created or become affiliated with 37 projects in the United States and abroad that are involved in the collection of testimonies.

"The original thought about the archive was that when we reached a collection of 1,000 testimonies, we'd close shop," says Hartman, who has been the faculty adviser to the Fortunoff Archive since its founding. "But our feeling changed, and we decided that any survivor who wanted to tell his or her story should be heard. We've had the good fortune of getting University support for that mission, starting with that of the late [Yale president] Bart Giamatti, recognizing that the testimonies are of significant educational value."

Recorded in some 20 different languages, the witness accounts range from 30 minutes to 40 hours (the latter recorded in several sessions), says Joanne Rudof, the archivist for the Yale collection. All of the interviewers at Yale are volunteers who participated in a six-week training course in 1984. Witnesses' testimonies are catalogued using only their first name and last initial to protect their privacy, but all those who testified have agreed to make their stories available to the public. (Glassner, who is an active public speaker about her Holocaust experience, volunteered to take part in this article independently of the Fortunoff Archive.)

"Our emphasis is always on letting the witness tell his or her story with as little interference as possible," says Rudof. "Questions might be asked to pinpoint a time or a place or elicit additional information, but the witnesses are the experts in their life stories, and our interviewing techniques have been developed with that in mind."

For Glassner, who lives in Hamden, Connecticut, the videotaping of her testimony was the first time she ever told the story of her years in hiding from beginning to end. Her ability to finally talk in the first person about her experiences, she said in a recent interview, arose during a trip to Poland in 1976, when she visited her childhood home and the sites where she hid from persecution, thus both physically and emotionally reconnecting with that traumatic part of her past for the first time.

Upon returning home, Glassner says, she welcomed the opportunity to make her story known through the Holocaust Survivors Film Project. She added to it in 1988 after the project had come to Yale.

In her videotaped account, she recalls how for more than a year she lived in the Jewish ghetto in Losice and how she was later separated from her family when her father paid a Polish police officer to take her into his home. During her five months there, Glassner spent much of her time in the darkness of a small wooden wardrobe closet, where she actually felt safe until the policeman's family, anxious about being discovered, began to talk about getting rid of her. Glassner recalls overhearing their murmurs about taking her out to a cemetery to be shot.

In her testimony, Glassner also describes how she was rescued by a farmer who had risked his life saving Jews. He reunited her with her parents, and she joined their life in an underground shelter -- a six-by-eight-foot pit beneath the farmer's animal shed -- from which the family members rarely ventured.

While the experience of reliving her past as she was taped was an emotional one, Glassner says that she was grateful for the opportunity.

"The telling was a little scary for me at first, but once I started going they couldn't have stopped me," says the Holocaust survivor, who has since become an active public speaker about her experiences. "Before I was taped, I used to say, 'I'm not a survivor; I didn't suffer.' My parents suffered, but my family of five survived intact. We were among the 16 people from Losice, out of 6,000 Jews from the town, who survived. In the telling of my story, I realized I was indeed a survivor. I walked with a gun behind my back three times when I was only a child. Remembering these things, I saw how I had cultivated a memory of a happy childhood that was a farce. Only part of it was happy."

Among the other testimonies in the collection are survivors' accounts of forced labor, life in Auschwitz and other concentration camps, and the recollections of rescuers who hid Jews and of soldiers who liberated the camps. An important addition to the archives are testimonies from Roma and Sinti (Gypsy) survivors, an initiative that is ongoing through the Yale collection's affiliation with a videotaping project in Slovakia.

One of the most important missions of the Yale archive is to promote in public schools and other educational settings the use of edited programs comprised of testimony excerpts, so that future generations will know the legacy of the Holocaust from both an historical and personal perspective, say Hartman and Rudof. The archive's staff has produced a library of video programs featuring edited versions of survivor accounts that are loaned to schools and community groups. The Yale archive is affiliated with the Holocaust Education/Prejudice Reduction Program, which serves as a resource to 14 New Haven-area school systems.

Nearly 100 patrons visit the Fortunoff Archive annually for their research and have used the testimonies in their books, articles and other publications. The archive has also been used by authors, artists, composers, musicologists, poets, playwrights, theatrical directors, filmmakers and television producers, says Rudof. Over the years some of the Yale graduate and undergraduate students who have helped in the day-to-day operation of the archive have become inspired to be scholars of the Holocaust themselves, says Hartman.

To make the archive easily accessible, the testimonies are catalogued in the Yale Library online public access catalog, ORBIS, as well as in an international bibliographic database. Bibliographic records for over two-thirds of the collection are included in these catalogs.

According to Hartman and Rudof, two essential goals for the archive's staff are to complete the online cataloging of videotapes and to preserve the recordings themselves. Many of the older tapes have recently been transferred to a more current format, and the tapes have been moved to a state-of-the-art storage facility to ensure they can be used for generations to come.

"The number of survivors and witnesses of the Holocaust are quickly diminishing," says Rudof, "thus making the taping of their recollections -- and the preservation of those tapes for a future world which will have no memory of this historical period -- all the more urgent."

Glassner says that while her contribution to the archive is a painful reminder of the atrocities committed against Jews and others, she hopes it also inspires hope.

"One of my reasons for telling my story is that I am an idealist who believes there is good in this world and that evil is not going to dominate the world forever," says the Holocaust survivor. "My hope is that stories like mine, in their expression of the evil, help to inspire that goodness."

The Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies is open to the public, by appointment, Monday-Friday, 8:30 a.m.-4:45 p.m. To make an appointment, call (203) 432-1879.

-- By Susan Gonzalez

T H I S

Bulletin Home

Fortunoff Archive is preserving survivors'

stories for 'a future world' W E E K ' S

W E E K ' S S T O R I E S

S T O R I E S![]()

Building quantum computer is goal of new Yale center

Building quantum computer is goal of new Yale center

![]()

![]()

Israel's Ehud Barak on peace prospects in Middle East

Israel's Ehud Barak on peace prospects in Middle East![]()

![]()

Ireland's Mary Robinson on 'ethical globalization'

Ireland's Mary Robinson on 'ethical globalization'

![]()

![]()

Tobacco settlement income going up in smoke, says study

Tobacco settlement income going up in smoke, says study![]()

![]()

Fortunoff Archive is preserving survivors' stories for 'a future world'

Fortunoff Archive is preserving survivors' stories for 'a future world'![]()

![]()

Journalists discuss Kashmir's role in Central Asian crises

Journalists discuss Kashmir's role in Central Asian crises![]()

![]()

Clot-busting drugs often improperly used, study finds

Clot-busting drugs often improperly used, study finds![]()

![]()

Show features Edwardian collector's 'unusual' acquisitions

Show features Edwardian collector's 'unusual' acquisitions![]()

![]()

Cats pose few risks for women who are pregnant, researchers say

Cats pose few risks for women who are pregnant, researchers say![]()

![]()

Wedgwood named to U.N. Human Rights Committee

Wedgwood named to U.N. Human Rights Committee![]()

![]()

Employees urged to take full advantage of their benefits

Employees urged to take full advantage of their benefits![]()

![]()

Reunion events will explore the intersection of law and the arts

Reunion events will explore the intersection of law and the arts![]()

![]()

SOM summit will address the current issues facing women business leaders

SOM summit will address the current issues facing women business leaders![]()

![]()

Dr. Boris Astrachan, former CMHC director, dies at age 70

Dr. Boris Astrachan, former CMHC director, dies at age 70![]()

![]()

Campus Notes

Campus Notes![]()

|

| Visiting on Campus

Visiting on Campus |

| Calendar of Events

Calendar of Events |

| In the News

In the News |

| Bulletin Board

Bulletin Board![]()

Yale Scoreboard |

| Classified Ads

Classified Ads |

| Search Archives

Search Archives |

| Deadlines

Deadlines![]()

Bulletin Staff |

| Public Affairs Home

Public Affairs Home |

| News Releases

News Releases |

| E-Mail Us

E-Mail Us |

| Yale Home Page

Yale Home Page